Nitrogen+Syngas 399 Jan-Feb 2026

26 January 2026

European ammonia imports

AMMONIA MARKETS

European ammonia imports

Europe is likely to become an increasing ammonia importer over the coming years as low global ammonia prices and high European gas prices squeeze producer margins, but CBAM remains a wild card.

Europe’s ammonia industry continues to struggle with high feedstock prices and increasing imports from outside the continent. CBAM will include carbon pricing into imported ammonia as it ramps up over the next few years, but increasing availability of relatively cheap low carbon ammonia may still allow for increased imports.

Feedstock prices

Since mid-2024 the European gas market has moved from crisis-era emergency buying and high price volatility toward a new equilibrium shaped by structural rerouting of supply, sustained LNG flexibility (especially from the United States), tighter policy on Russian energy, and a price regime that is much lower than the 2022–23 peaks but still sensitive to winter weather and geopolitical shocks. The European Union has extended its gas storage obligations and built more flexibility into the timing and compliance mechanics through to 2027, reducing some of the “rush-to-fill” distortions while preserving winter security. By 1 January 2026, aggregate storage was around ~62% full – lower than the pre-2025 peaks, but not critically low. Europe has also continued to add regasification capacity, including FSRUs in Germany.

Pipeline gas flows from Russia have continued to decline as a share of Europe’s imports, while pipeline supply from Norway has become the largest single pipeline source. At the same time, LNG, dominated by cargoes from the United States, became the marginal swing supply that European buyers used to balance winter shortfalls and replace lost pipeline volumes. The effective end of large-scale Russian gas transit via Ukraine around 1 January 2025 materially rerouted flows and added a persistent risk premium for central/ eastern Europe until alternative routings and LNG volumes were fully operational, leading to a price spike with the Dutch TTF forward rate rising to roughly €50/ MWh in early January 2025 and €58/ MWh in February 2025. But by late 2025 the market had softened, and TTF rates traded down to the high €20s/low €30s/ MWh range, driven by mild weather expectations, strong LNG arrivals and comfortable European supplies. Even so, this still represents a price of around $9.70/MMBtu, three times higher than US gas prices and a significant increase on major fertilizer supplying regions such as the Middle East, Trinidad and Russia.

In the medium term, US Henry Hub prices are expected to rise to $3.60/ MMBtu by 2030, due to cost inflation and greater feedstock consumed for LNG export. Conversely, Dutch TTF prices are forecast to fall to an average of $8/MMBtu by 2030, lowering some of the price gap. But structurally higher European feedstock prices are expected to lead to reduced domestic ammonia production over the medium to longer term.

Russian imports

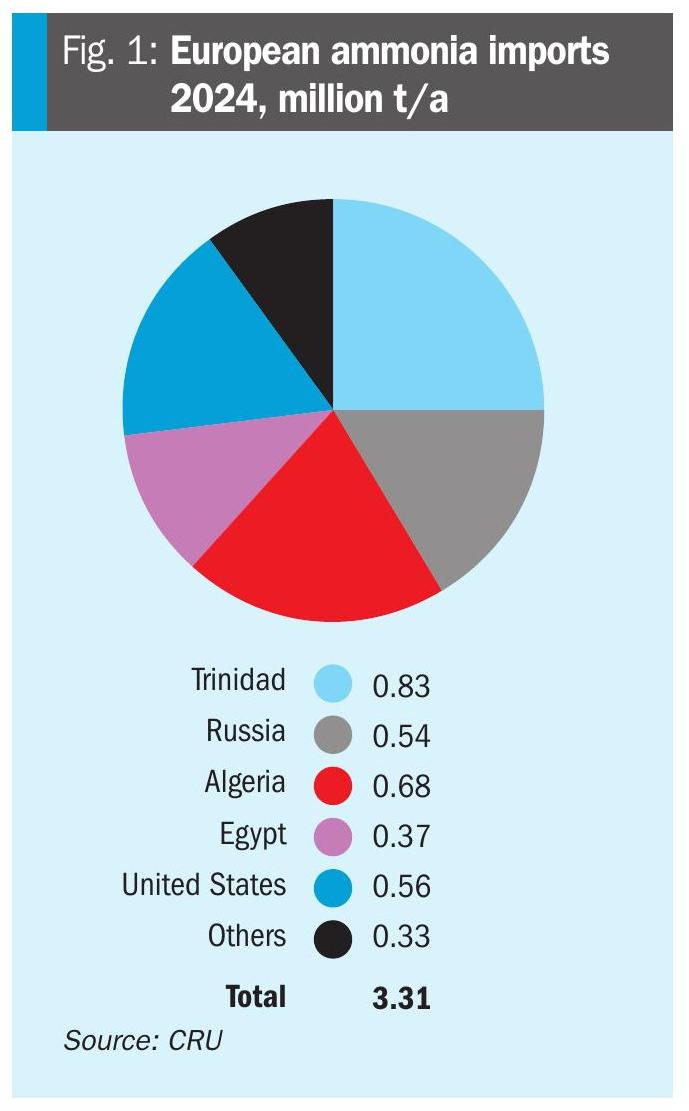

Set against the cost of producing ammonia within the EU has been the question of cheap imports from outside, especially Russia. There is a concern that, while Europe has reduced its dependence on Russian natural gas, in importing fertilizer instead, it is merely swapping one dependence for another. Most of this is ammonium nitrate and urea, however. On the ammonia side, Europe only imported 540,000 tonnes from Russia in 2024, as shown in Figure 1, representing only 16% of the 3.3 million tonnes imported that year.

Tariffs

One way that the EU has attempted to deal with this is via the imposition of tariffs and other restrictions on Russian fertilizer imports. Fertilizers were not initially subject to sanctions, but as time has gone by, while the EU has not applied a blanket ban on all Russian fertilisers, it has layered measures that substantially restrict and tax such imports, including a new, phased tariff regime on certain fertilisers from Russia and Belarus (in force from 1 July 2025 and escalating over several years); and existing antidumping duties on ammonium nitrate and UAN – measures that have been subject to expiry reviews. These measures are intended to sharply reduce imports and revenues while preserving narrow foodsecurity/transit exceptions.

US tariffs also complicate the picture. President Trump announced an amendment to the administration’s reciprocal tariffs effective from November 13, 2025, which exempted critical fertilizers such as urea, ammonium nitrate, UAN, ammonium sulphate, DAP, and MAP from tariffs in order to provide relief to US farmers. However, ammonia was not one of the fertilizers named, and the eligibility of ammonia shipments for tariff relief will be determined on a case-by-case basis by the Secretary of Commerce and the US Trade Representative, depending on the status of trade talks with exporting nations. This could still place additional burdens on, e.g. Trinidadian exports to the US, potentially pushing them towards Europe instead.

CBAM

The other tariff-like restriction is carbon taxes, and the start of 2026 has seen the first costs imposed under the EU’s new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). CBAM is a levy on carbon-intensive goods entering the EU, and the price of CBAM certificates will reflect the EU ETS prices corrected for any free allowances EU producers still receive, and carbon costs incurred during the production process in the producing country. The CBAM aims to mitigate possibly unfair competition from the hydrogen and fertilizer industry outside the EU that doesn’t face any carbon-related regulation. This should, in theory, significantly mitigate the eroding competitiveness of the fertilizer industry in Europe versus fertilizer producers from abroad.

The initial impact seems to have been to slow ammonia imports into northwest Europe, with no further spot sales into the region confirmed in the first week of January. Default CBAM values released by the European Commission in late December have effectively priced US material out of the European market. The free allocation for ammonia is identical under both the case of suppliers reporting a verified emissions intensity and the case of using the default method. This value is set at 1.52 tonnes CO2/t ammonia, which represents the amount of embedded emission in the ammonia that importers are not liable to pay a CBAM charge on. Where the methods differ is in the emissions intensity level to be used in calculating the emission liable to CBAM. In the case of suppliers providing actual, verified data, this value is plant-specific. In the default method, the emissions intensity is set based on country-level averages, with a 1% adjustment upwards to encourage suppliers and importers to move off the default method. The default emission intensities for ammonia for the EU’s major trading partners are 2.10 tCO2/t for Algeria, 2.28 tCO2/t for Russia, 2.44 tCO2/t for Trinidad and 3.44 tCO2/t for the US. It is unclear how the US was assigned its very punitive default value, given the dominance of natural-gas-based ammonia production in the country, which typically sees emissions intensities around 2 tCO2/t ammonia. The impact of this is substantial if US producers intend to rely on default values, with importers liable to significantly higher CBAM charges; US suppliers will have to report actual, verified emissions to avoid the prohibitive charge.

The effect has been to effectively price US ammonia out of the EU market. In the near term, European buyers are expected to favour Egyptian and Algerian tonnes, which carry the lowest default values, although availability from these origins remains tight. Trinidadian, Algerian and Egyptian ammonia also arrive duty-free into Europe. US ammonia will attract a CBAM charge of around $175/t under the default value and is also subject to a 5.5% import duty. Saudi and Russian ammonia also face a 5.5% import duty.

Longer term, however, a number of large capacity blue ammonia plants in the US Gulf Coast are likely to attract much lower rates under CBAM and could become a major source of supply to Europe.

Increased imports

Europe’s ammonia market faces significant challenges as rising global capacity drives oversupply and pushes prices down, while structurally high site costs in Europe make operations less profitable. Stringent emissions regulations (EU’s ETS), elevated energy prices, and growing global competition have already weighed on operating rates, with Western Europe’s plants expected to run at just 81.3% in 2025 which is below historical levels. The forecast was revised upwards in line with the baseline from higher actual production figures and a softer TTF price outlook.

Overall, these challenges have led to plant closures and curtailments, including the mothballing of Yara’s Hull plant in the United Kingdom and Achema in Lithuania intermittently halting production since 2022, as producers struggle to compete with lower cost suppliers. With domestic production becoming less viable, Europe will increasingly be reliant on imports from regions with cheaper energy and lower carbon intensity.

Over the next few years, CRU expects that European imports will grow steadily, increasing by 1.79 million t/a between 2026 and 2030 as declining ammonia prices narrow domestic margins and support higher import demand. Additionally, the EU’s CBAM will also encourage imports of low emissions ammonia by gradually phasing out free allowances, further supporting import growth.

Downstream production

While ammonia imports increase, European downstream fertilizer assets are expected to continue to operate. Margins for ammonium nitrate, a product which can consume imported ammonia, showed relatively similar figures for domestic European production via imported ammonia ($113/t) versus domestically produced ($141/t) ammonia in 2024. The introduction of CBAM is expected to improve things for EU nitrate producers. European producers are already subject to carbon costs under the EU ETS – by 2026, they are expected to pay around $7 /t more for AN than in 2025, based on the weighted European average FGAN emission. This incremental increase improves the relative competitiveness of domestic producers, as imports were not previously subject to equivalent costs. Carbon costs are expected to rise steeply, driven by the phase-out of free allowances and increasing carbon prices. This creates an opportunity for low-emission AN, which could reduce carbon costs by around 89% by 2030.

EU urea remains roughly break-even with imported. EU urea imports from Russia reached their highest monthly level in Jun 2025, in preparation for tariff implementation, but thereafter saw a major slowdown during 2025 Q3, with imports totalling well below 2022–2024 levels. Based on trend in the second half of 2025, an increase in imports to the average over 2022–2024 H1 during 2026 H1 will avoid the threshold of 2.7 million t/a to trigger higher tariffs. Imports are likely to switch towards North Africa, where, although producers are subject to CBAM, they will continue to enter duty-free, unlike other regions.