Nitrogen+Syngas 399 Jan-Feb 2026

21 January 2026

Future-proofing blue ammonia

DECARBONISATION

Future-proofing blue ammonia

VK Arora of Kinetics Process Improvements, Inc. (KPI) evaluates deep decarbonisation pathways for a new build ammonia plant of 3,500 tonnes/day on the United States Gulf Coast. Eight technology configurations are compared with results providing a framework for technology selection, balancing emissions reduction, process integration, and indicative economics.

Ammonia is increasingly viewed as an important contributor to low carbon energy systems, serving as a carrier of hydrogen, a carbon free fuel, and an essential chemical feedstock. Although global demand for low carbon ammonia is still developing, and while markets for green ammonia remain limited, deep decarbonised blue ammonia is emerging as the most practical near-term option – offering a practical pathway for early large-scale deployment due to established reforming technologies, expanding carbon capture projects, and favourable natural gas supply.

This study evaluates eight process configurations for a 3,500 tonnes/day ammonia plant on the United States Gulf Coast, including: steam methane reforming (SMR); secondary reforming (SR); pre-combustion CO2 capture, compression and dehydration for sequestration (PCCS); post and pre-combustion CO2 capture, compression and dehydration for sequestration (PoPCCS); autothermal reforming (ATR), partial oxidation (POx), convective reforming (CR), nitrogen wash unit (NWU), nitrogen wash unit with recycle (NWUR), two-stage pressure swing adsorption (PSA+) for hydrogen purification, and hydrogen-rich firing (H2Fire). All schemes include feed purification, pre-reforming (where applicable), and integrated steam systems. The region provides low-cost natural gas, significant carbon dioxide storage capacity, and mature industrial infrastructure, which together enable deep decarbonisation at scale. Together, these factors enable deep decarbonisation at commercially viable scale, positioning Gulf Coast blue ammonia as a bridge technology toward longer-term hydrogen economy goals.

Technology configurations

The following blue ammonia production process schemes were broadly evaluated for high to deep decarbonisation options:

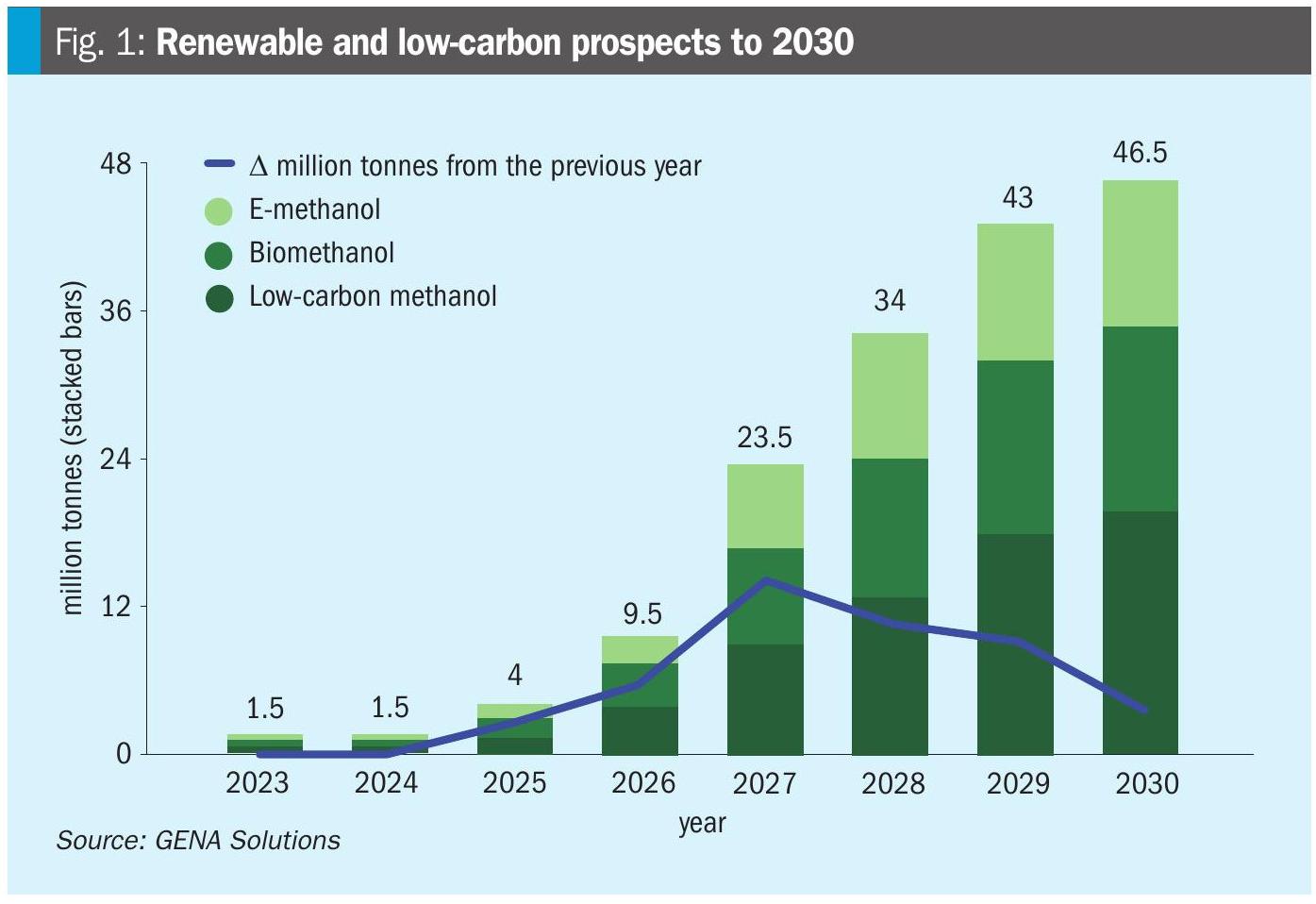

- Case 1: SMR + SR + PCCS

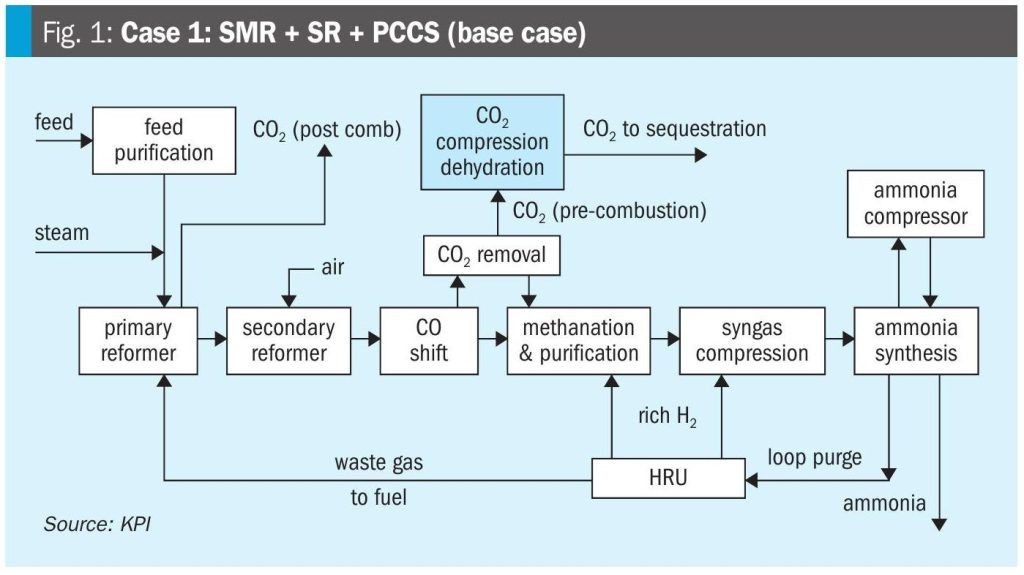

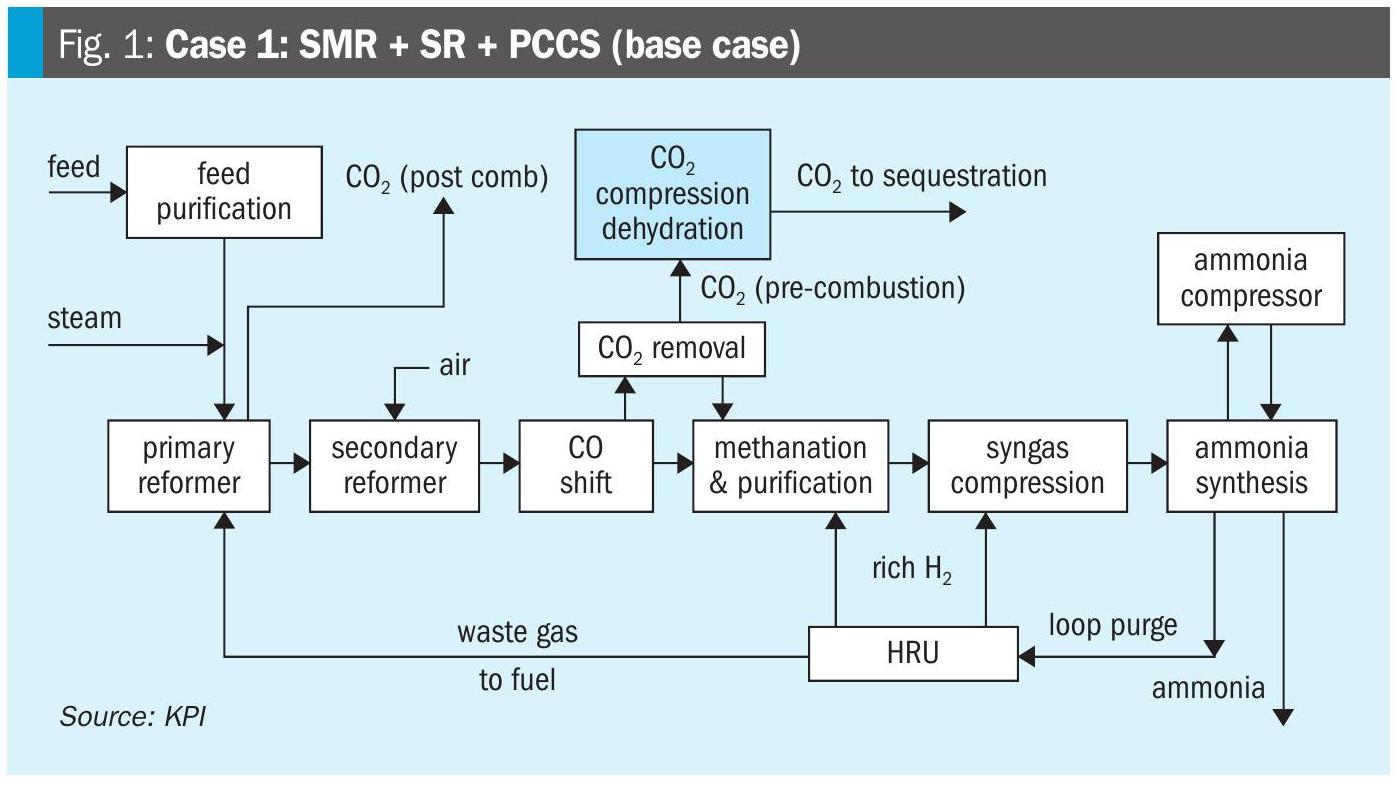

- Case 2: SMR + SR + PoPCCS

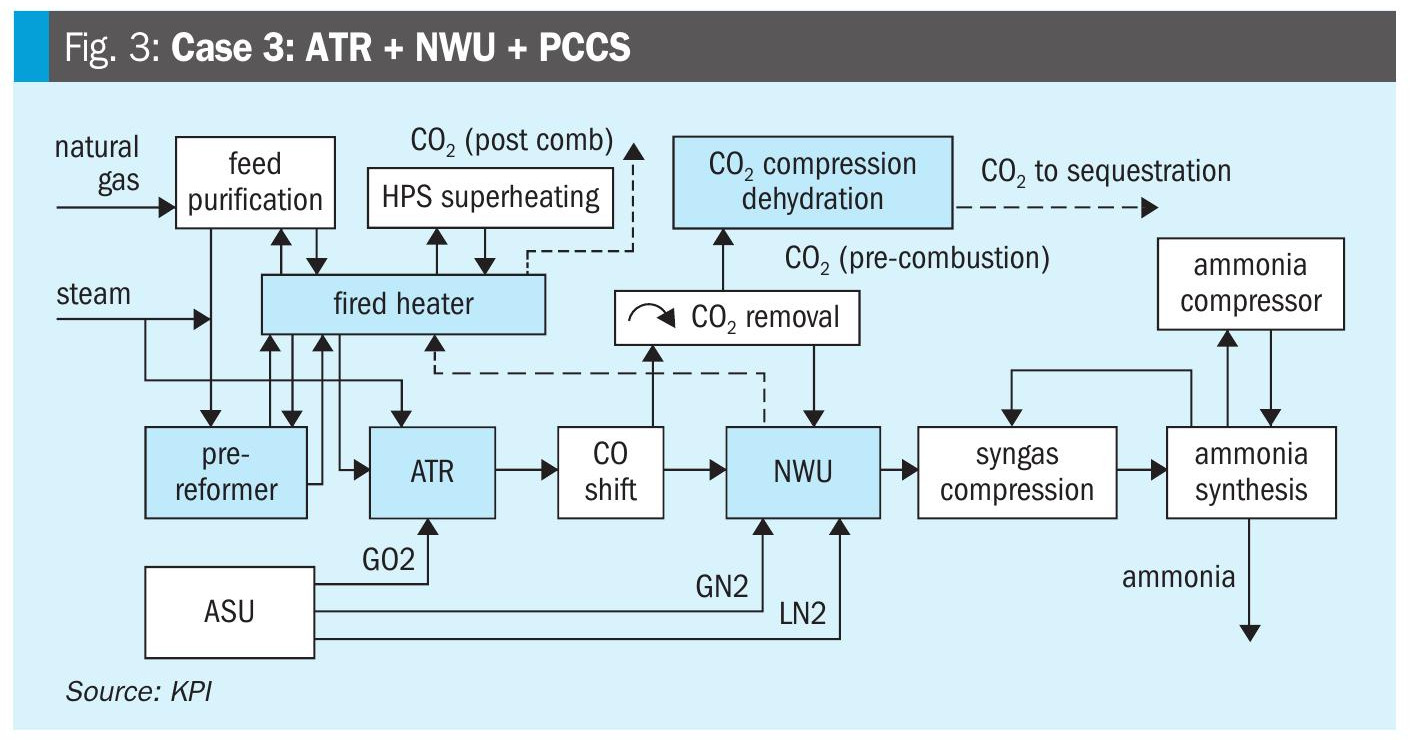

- Case 3: ATR + NWU + PCCS

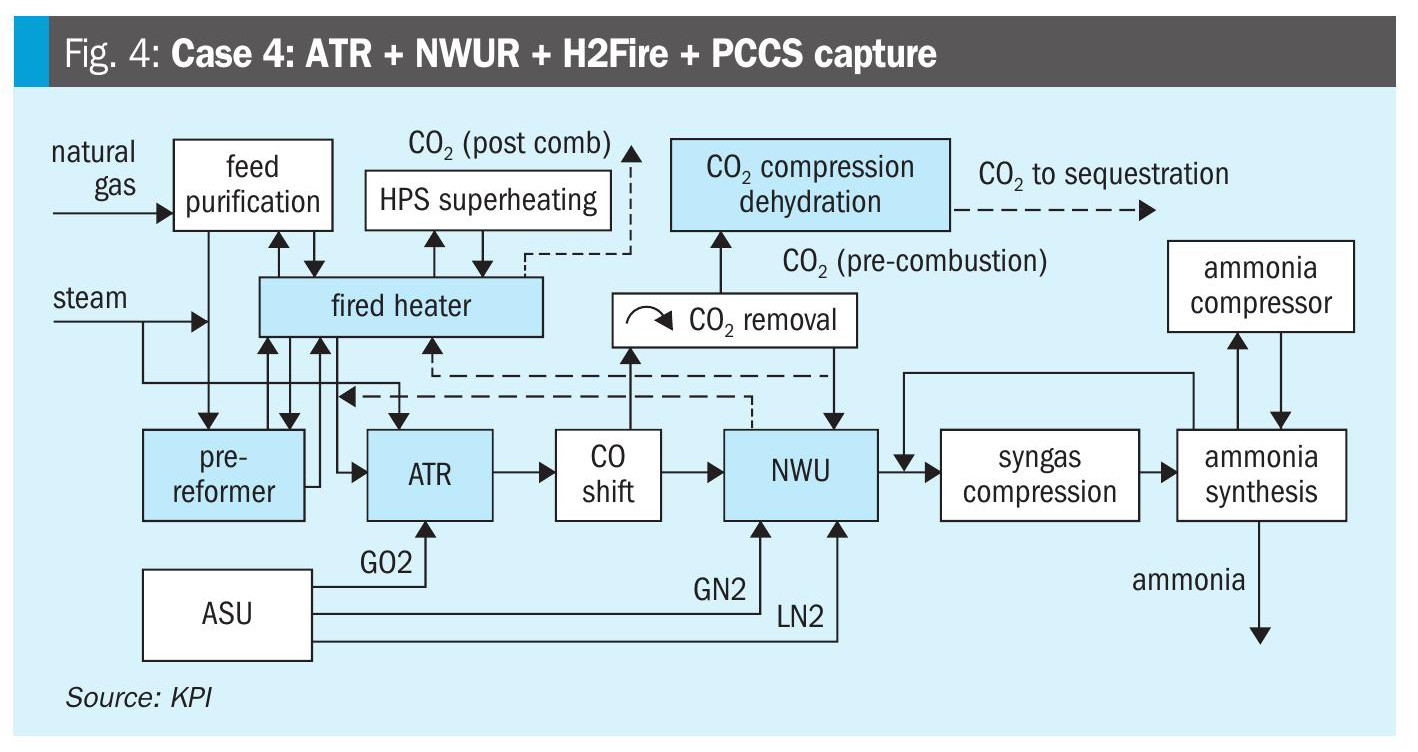

- Case 4: ATR + NWUR + H2Fire + PCCS

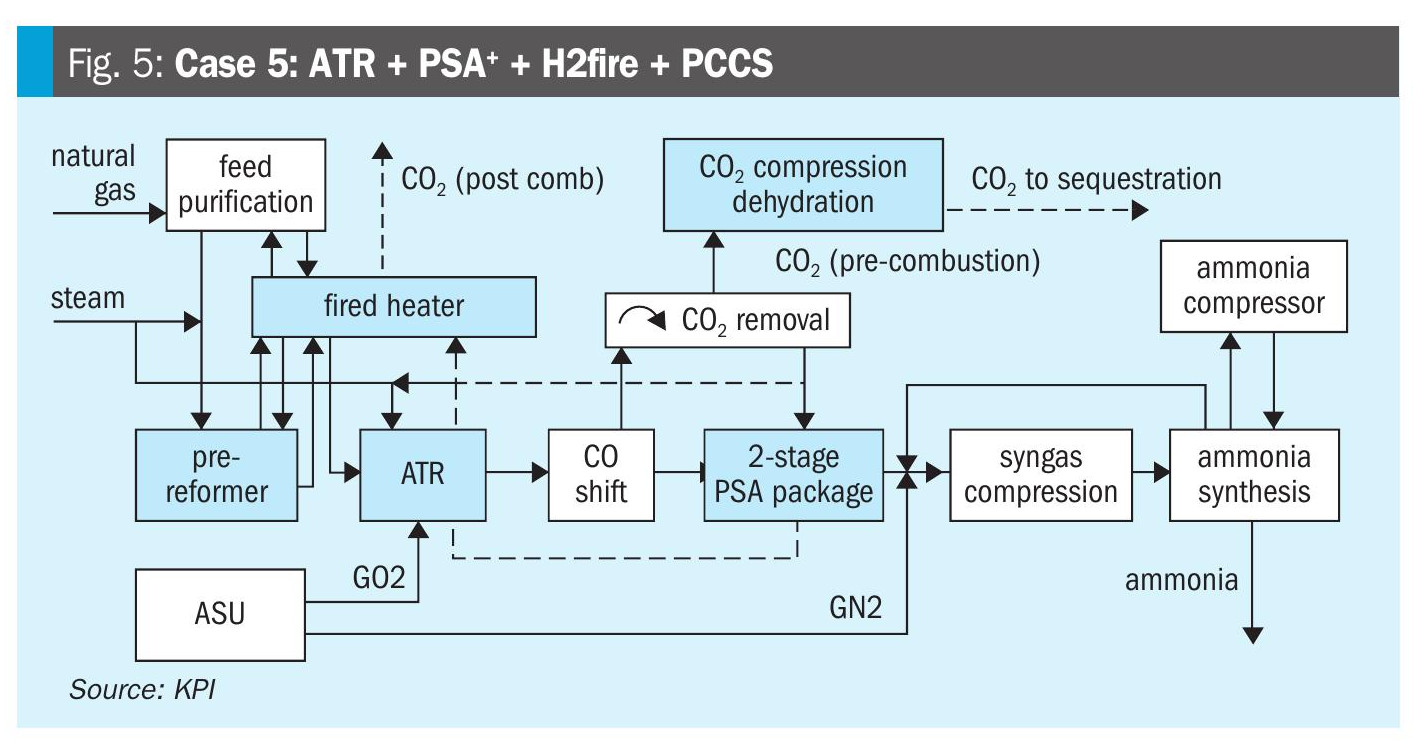

- Case 5: ATR + PSA+ + H2fire + PCCS

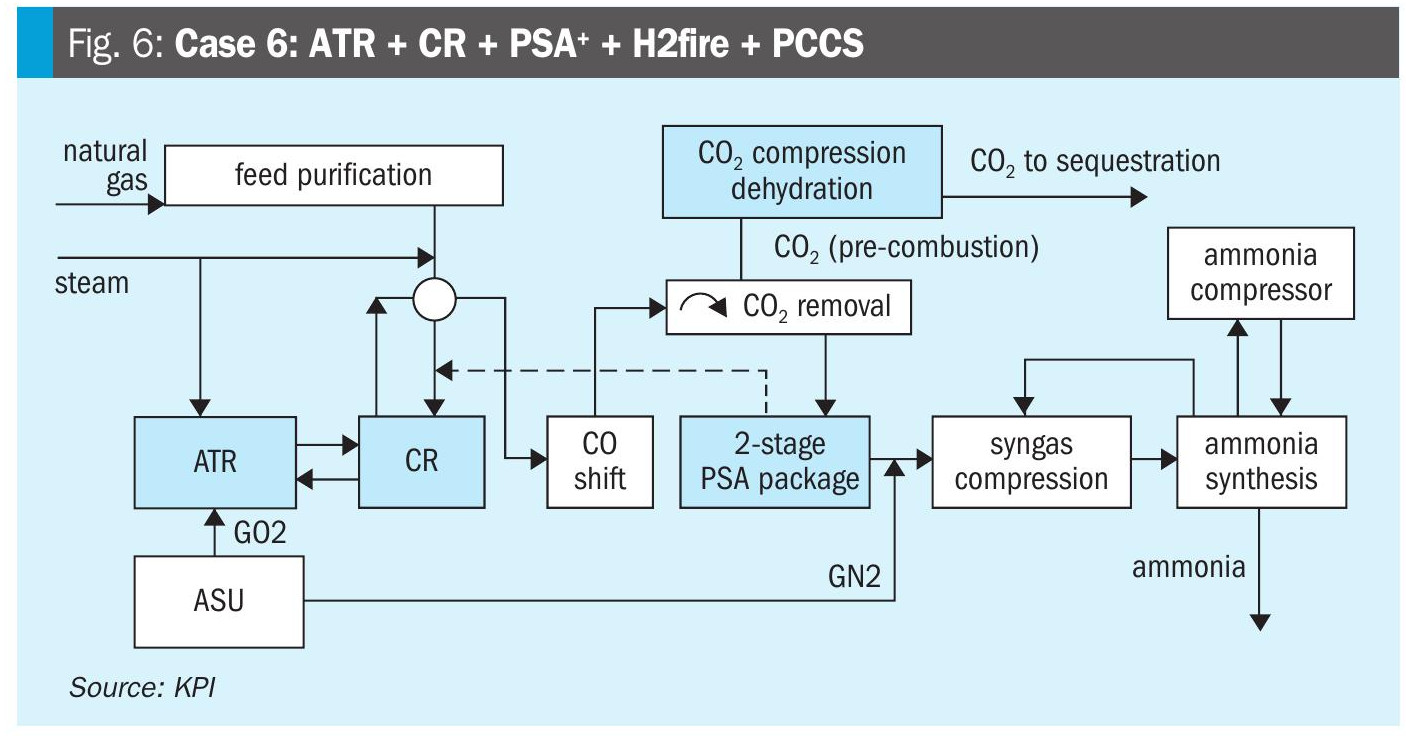

- Case 6: ATR + CR + PSA+ + PCCS

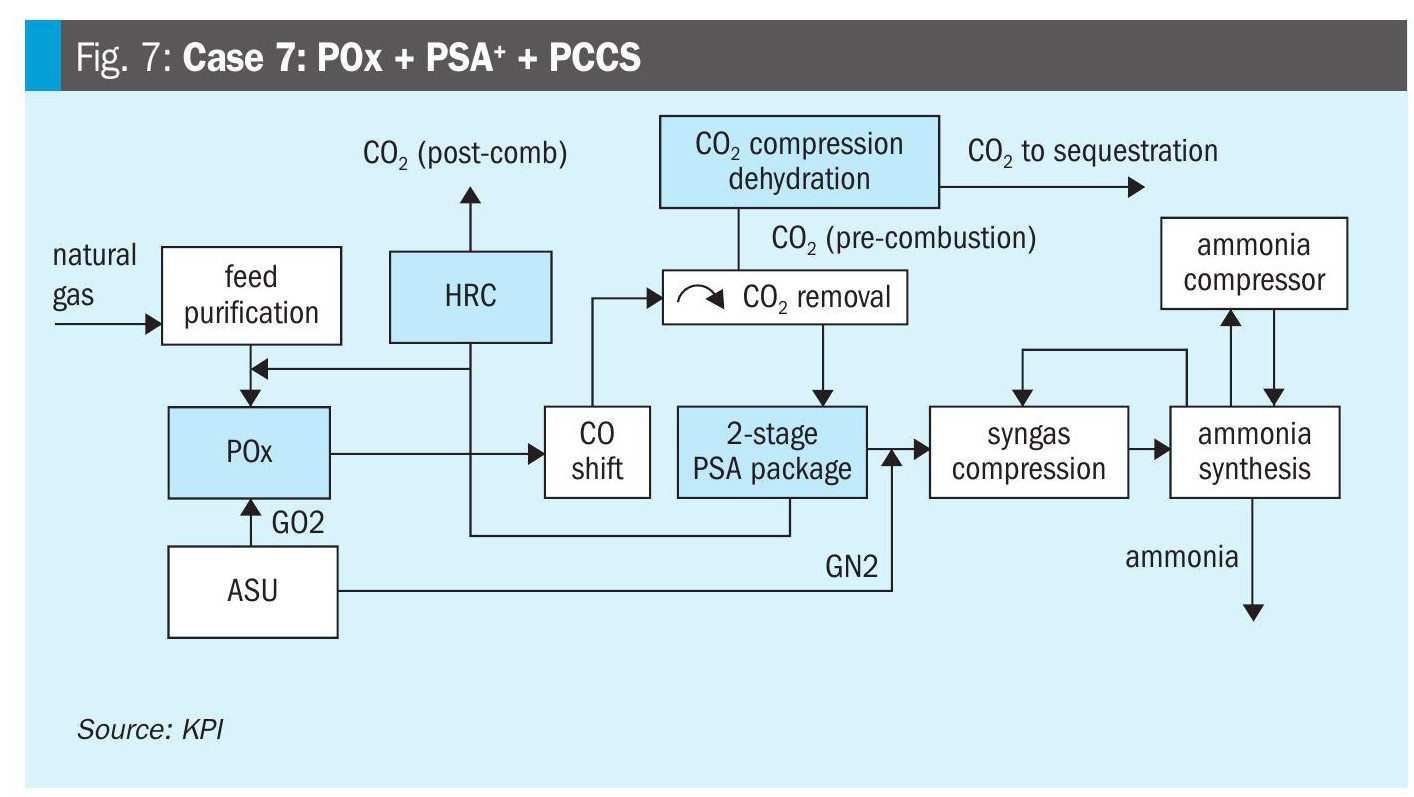

- Case 7: POx + PSA+ + PCCS

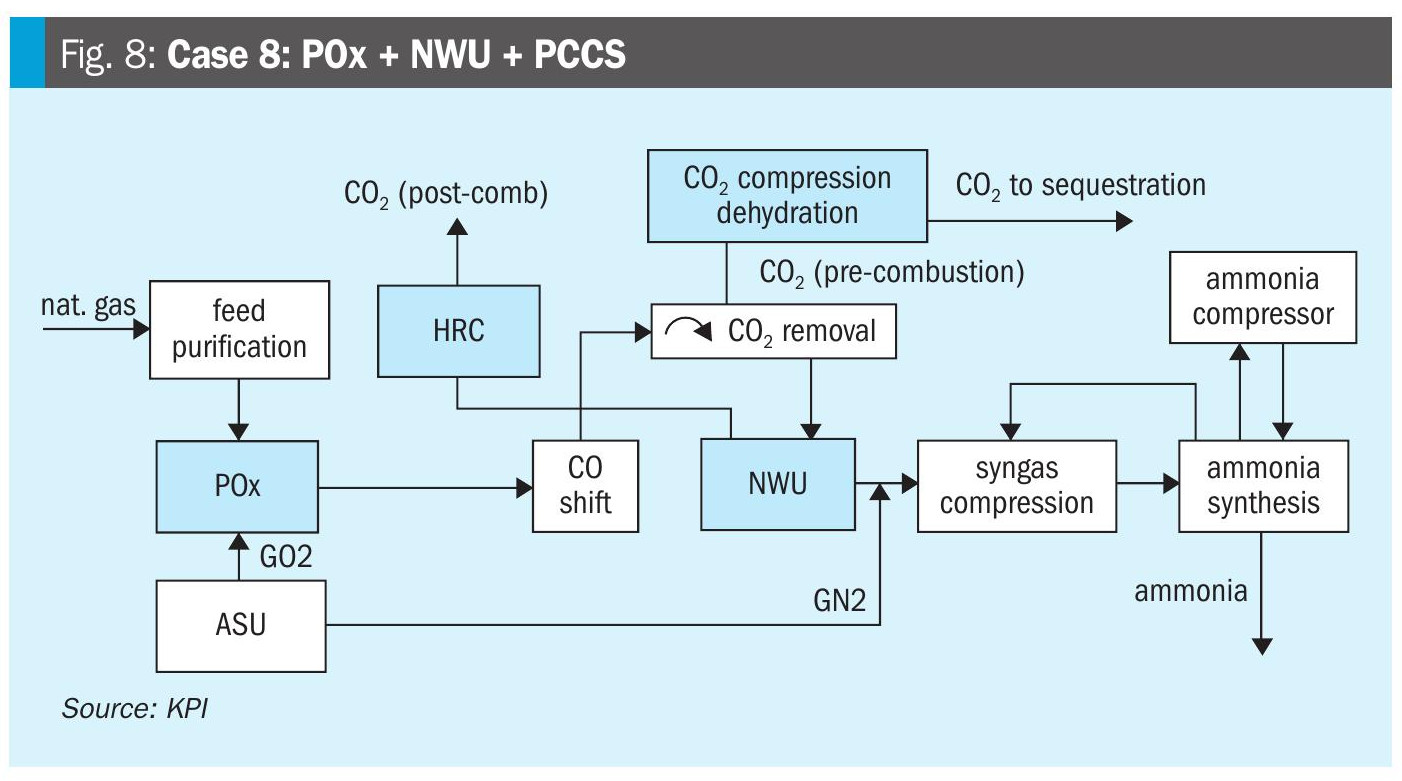

- Case 8: POx + NWU + PCCS

A brief review of catalytic methane pyrolysis (CMP) is also included as an emerging low carbon alternative.

All cases were evaluated under a common basis. Scope 1 and Scope 2 carbon intensities were estimated using standardised capture efficiency and regional grid assumptions. Results highlight differences in carbon capture performance and natural gas consumption.

Hydrogen purification options were examined by comparing nitrogen wash and two-stage PSA (PSA+ ), with and without recycle, to understand their impact on recovery, energy use, and integration.

Case description

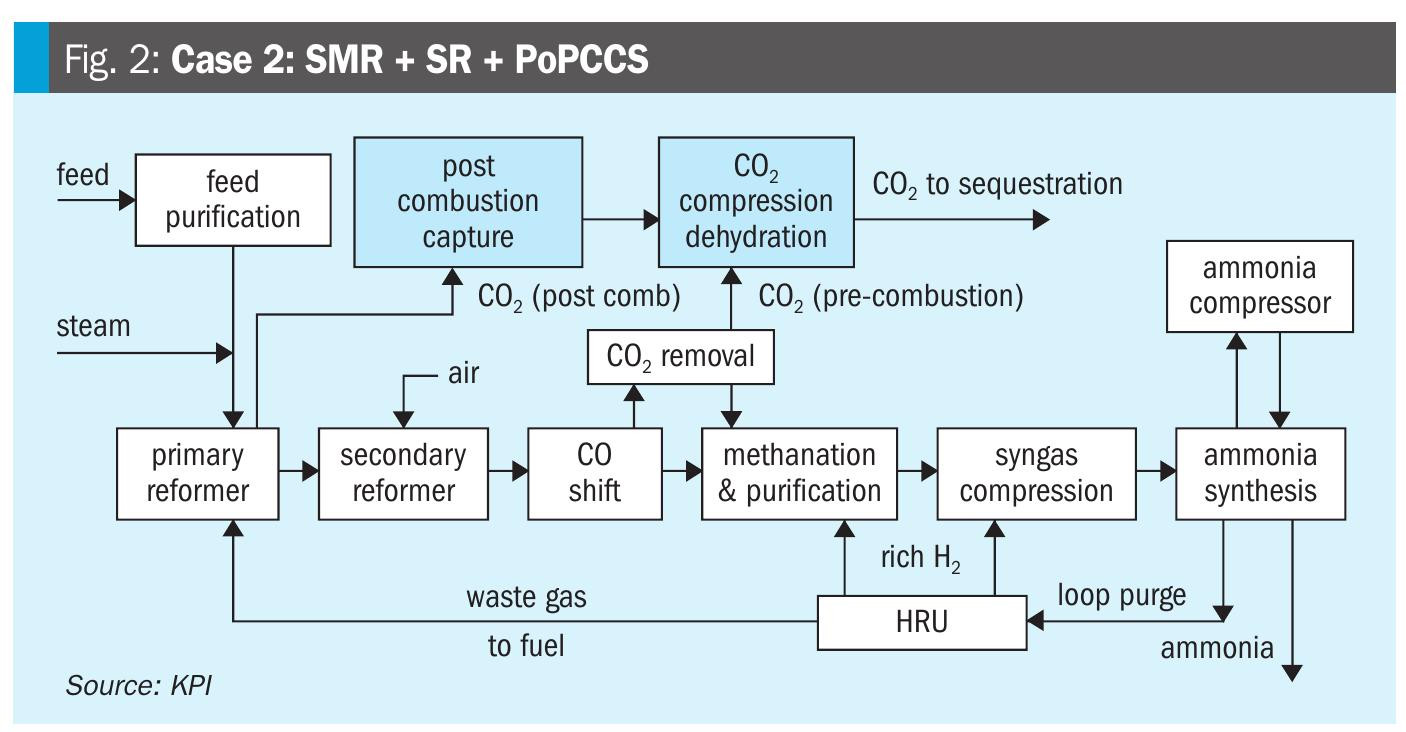

Each configuration (see process schematics in Figs 1-8) is briefly described to highlight the major process steps, integration features, and carbon management approach used in the evaluation.

Case 1: SMR with SR and pre-combustion capture

This base case (see Fig. 1) represents a conventional but modern configuration widely deployed in commercial ammonia plants. It includes steam methane reforming followed by secondary reforming, along with compression and dehydration of captured pre combustion carbon dioxide for sequestration. This configuration provides moderate decarbonisation with well-established technology and operational reliability.

Case 2: SMR with SR and combined pre-combustion and post-combustion capture

This case (see Fig. 2) builds on Case 1 by capturing carbon dioxide from the reformer stack and combining it with the pre combustion carbon dioxide stream for compression and dehydration, enabling deeper decarbonisation. This approach enables deeper decarbonisation while maintaining the core SMR/SR process configuration.

Case 3: ATR with nitrogen wash and pre-combustion capture

This configuration (see Fig. 3) employs autothermal reforming operated at the lowest commercially viable steam-to-carbon ratio. Oxygen and process nitrogen are supplied by an integrated air separation unit (ASU). Hydrogen purification is performed in a nitrogen wash unit. Separate fired heaters provide process preheating and high-pressure steam superheating, using natural gas blended with plant off-gas as fuel.

Case 4: ATR with nitrogen wash recycle, hydrogen-rich firing and pre-combustion capture

This case (see Fig. 4) extends Case 3 by recycling carbon-containing streams to the ATR and using internally generated hydrogen-rich fuel for fired heaters. Recycling increases front-end equipment size and oxygen demand but significantly reduces carbon intensity – potentially improving project value under carbon pricing mechanisms or low-carbon certification requirements.

Case 5: ATR with two-stage PSA, hydrogen-rich firing and pre-combustion capture

This scheme (see Fig. 5) replaces the nitrogen wash unit with a two-stage pressure swing adsorption system to achieve hydrogen recovery comparable to nitrogen wash. Fired heaters utilise hydrogen-rich fuel for deep decarbonisation. As in Case 4, the front end enlarges due to higher hydrogen production requirements, but lower carbon intensity may offset increased capital costs depending on regional carbon policy and project financing terms.

Case 6: ATR with convective reforming, two-stage PSA and pre-combustion capture

This case (see Fig. 6) adds a convective reformer in series with the ATR and operates at a higher steam to carbon ratio. The convective reformer recovers high temperature heat to provide additional reforming duty, reducing natural gas and oxygen demand but lowering high pressure steam generation. The larger front end is balanced by improved carbon intensity under deep decarbonisation targets.

Case 7: POx with two-stage PSA and pre-combustion capture

This scheme (see Fig. 7) uses partial oxidation and PSA+ , which operates at much higher temperature than ATR and requires no catalyst. Oxygen demand is slightly higher, but methane slip is significantly lower. Integrated heat recovery for process preheating and high-pressure steam superheating eliminates the need for direct-fired heaters, further reducing emissions.

Case 8: POx with nitrogen wash and pre-combustion capture

This case (see Fig. 8) is similar to Case 7 but employs a nitrogen wash unit for hydrogen purification. No nitrogen wash recycle is applied. Despite the absence of recycle, the configuration still achieves approximately 97% carbon capture due to the inherently low methane slip characteristic of partial oxidation technology.

Steam system

The high-pressure steam level and degree of superheat were suitably selected for each configuration to minimise fired heater duty and reduce overall carbon intensity. Steam turbine drives were employed for major compression equipment (syngas and ammonia compressors) when sufficient HP or MP superheated steam was available; otherwise, motor drives were used to maintain energy efficiency. Surplus superheated high-pressure steam was expanded through back-pressure or condensing turbines for power generation, with net electricity credited as plant export. All other OSBL equipment, including the ASU, used motor drives, while the high-pressure boiler feedwater pump operated on steam or on motor as required. Process steam for the water-gas shift reactors was supplied from the process condensate stripper and the medium-pressure steam header. A minimum steam-to-gas ratio of 0.5 was maintained at the shift reactor inlet, with higher ratios applied as needed to control shift outlet temperature within catalyst and metallurgical limits.

Emissions and carbon intensity evaluation

Carbon intensity calculations encompass Scope 1 direct emissions (combustion and process releases) and Scope 2 emissions from imported grid electricity (Louisiana regional grid factors). Pre-combustion capture efficiency was set at >99.99% (conventional acid gas removal), while post-combustion capture was limited to 95% (current amine technology). Upstream natural gas emissions are excluded, consistent with project-level carbon accounting boundaries.

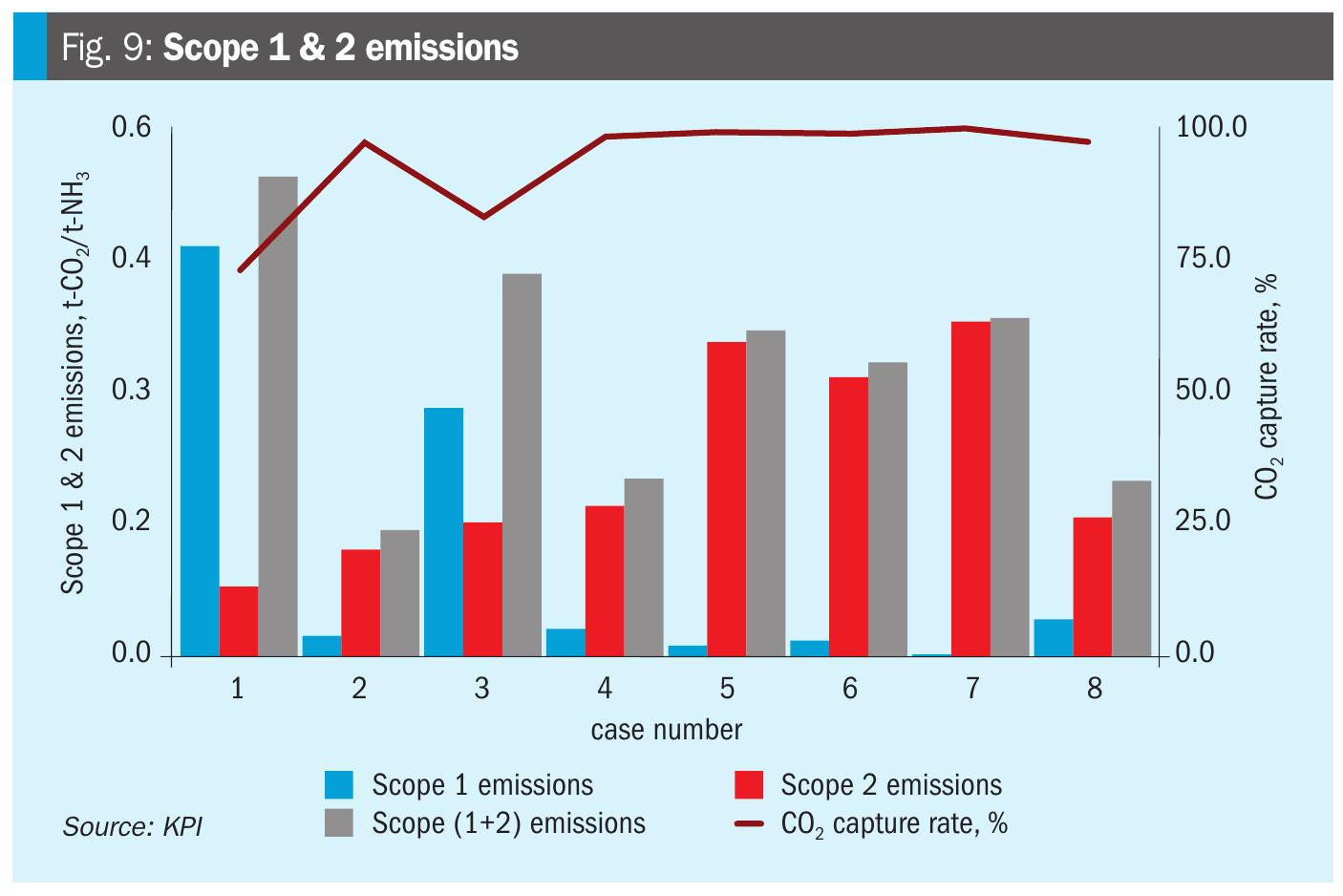

Fig. 9 illustrates significant differences across configurations. Case 2 achieves modest improvement through combined capture but remains constrained by the 95% post-combustion ceiling, leaving residual flue gas emissions that prevent ultra-low carbon intensity thresholds required for future certification schemes.

Cases 4 to 6 deliver the lowest carbon intensities by concentrating CO2 in syngas for efficient pre-combustion capture, maximising hydrogen recovery, employing carbon recycle or convective reforming, and utilising hydrogen-rich fuel that eliminates fired heater stack emissions, enabling capture rates exceeding 98%.

Partial oxidation Cases 7 to 8 achieve comparable performance due to inherently low methane slip, stable high-temperature conditions favouring complete conversion, and elimination of direct-fired heaters through integrated heat recovery. Multiple technology pathways achieve similar targets, offering developers flexibility based on site-specific conditions and risk preferences.

Process recycle reduction for lower carbon intensity

Lower carbon intensity can be achieved by minimising recycle, which requires reducing CH4 and CO in the syngas/H2 stream. Methane slip is primarily addressed under reforming operating conditions set for each configuration, leaving limited scope for further reduction. CO, however, can be lowered to single-digit ppm using either conventional methanation or selective catalytic oxidation.

Hydrogen purification: PSA vs nitrogen wash

ATR and POx with PSA differ from nitrogen wash in separation method. PSA uses cyclic adsorption to remove impurities, while nitrogen wash relies on cryogenic separation integrated into the synthesis loop. This difference influences energy use, integration, and flowsheet optimisation. Single-stage PSA provides lower hydrogen recovery, increasing feed demand, but its larger off-gas stream supports steam generation and reduces net power consumption. Two-stage PSA achieves recoveries comparable to nitrogen wash, though with additional compression duty.

Nitrogen wash offers high hydrogen recovery and direct loop integration suited for large plants, but requires refrigeration, has higher capital intensity, and provides less modular flexibility. The choice depends on site-specific economics, integration potential, and operating constraints.

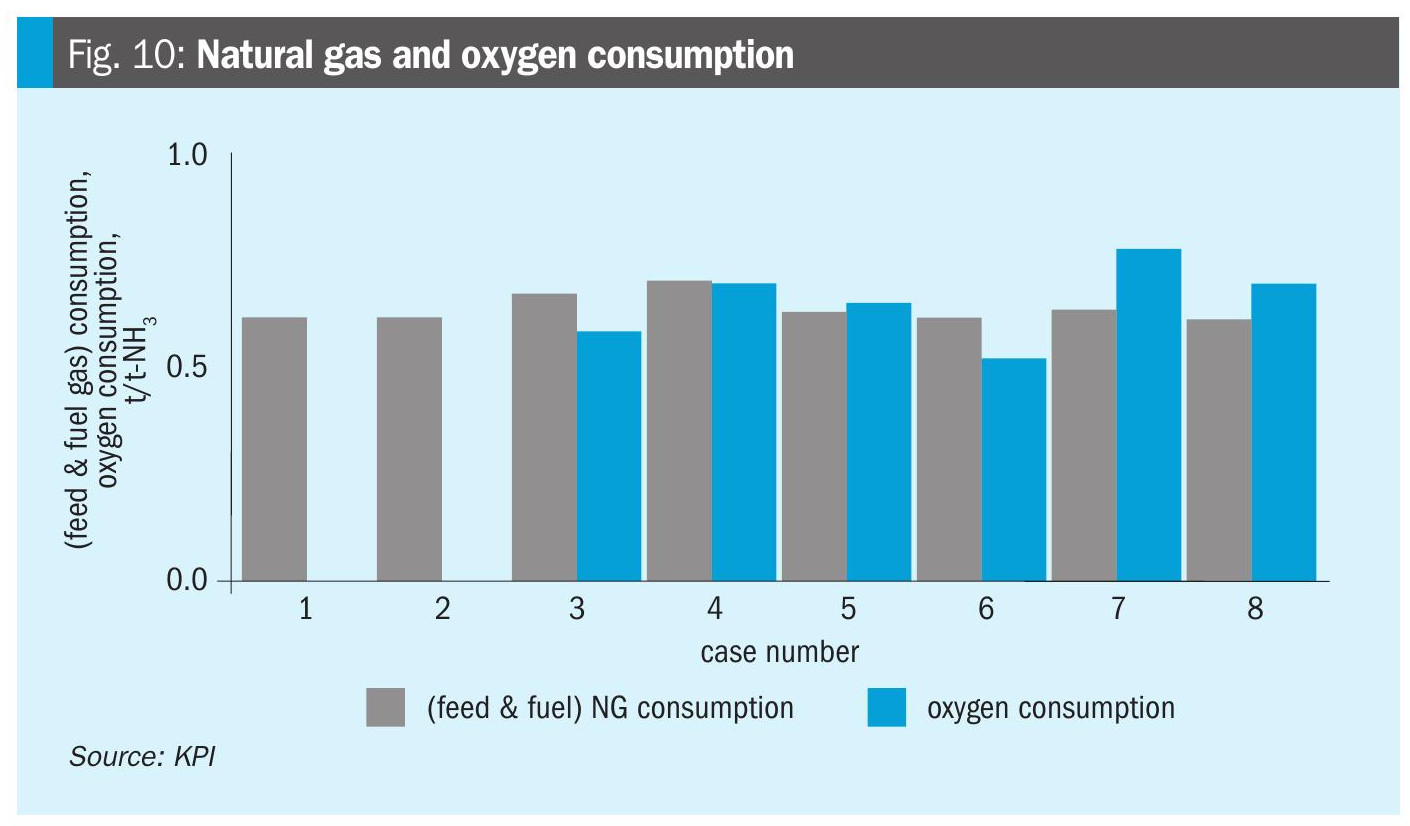

Comparison of feedstock, fuel, and major utility needs provides insight into operating characteristics across the eight cases. Fig. 10 shows clear differences Column widths, in feed, mm fuel, and oxygen use. Case 2 uses moderate natural gas without oxygen, but lowering carbon intensity through hydrogen-rich firing would increase natural gas demand and require major heater modifications.

ATR-based Cases 4 and 5 consume more natural gas and oxygen because recycle and higher syngas flow generate hydrogen-rich fuel. Case 6 behaves differently: the convective reformer recovers high-temperature heat for additional reforming, reducing feedstock and oxygen consumption but lowering high-pressure steam generation. Consequently, the steam system cannot support large syngas and ammonia compressors, requiring motor drives.

POx-based Cases 7 and 8 achieve deep decarbonisation through simplified heat integration: availability of additional process heat permits process preheating and steam superheating and eliminates fired heaters entirely while maintaining exceptionally low methane slip and stable carbon capture performance.

Residual CO removal

Selective CO oxidation represents a future improvement option for completely removing residual CO from shifted syngas (down to single-digit ppm levels) to minimise off-gas recycle to the front end (ATR or POx), reduce carbon intensity, and lower both capital and operating costs.

Selective CO oxidation removes CO without hydrogen penalty or inert buildup, improving loop efficiency and carbon dioxide capture. Challenges include sensitivity to gas impurities, limited commercial experience, and precious metal catalyst costs. It offers promising carbon intensity reduction for large-scale ammonia projects, but long-term reliability and economics require careful evaluation before widespread adoption.

Methanation is not a viable option for deep decarbonisation schemes as it consumes hydrogen and forms methane, which dilutes the synthesis loop, increases purge losses, and raises carbon intensity by converting captured carbon into an uncaptured form.

Techno-economic viability

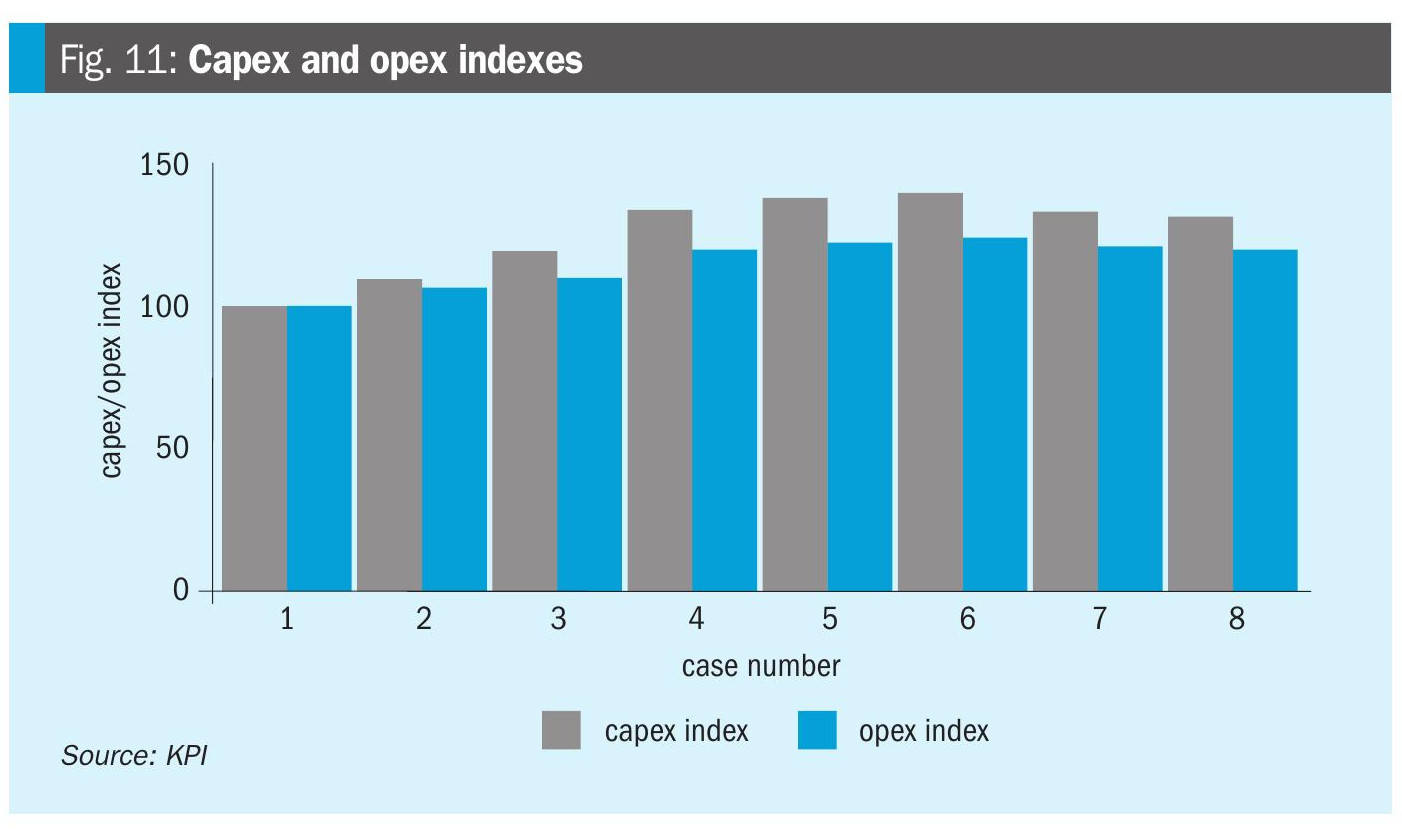

Economic performance review highlights important cost and long-term value differences across the eight cases. Fig. 11 shows Case 2 (SMR with SR and post-combustion capture) yields lowest capital and operating costs among deep decarbonisation pathways, but this advantage weakens when operational reliability is considered. At 3,500 t/d scale, the post-combustion system becomes extremely large, creating challenges with solvent handling, corrosion, foaming, aerosol formation, and parasitic power demand – reducing availability and increasing lifetime costs. Case 2 is also constrained by the 95% post-combustion capture ceiling (Fig. 9), preventing ultra-low carbon intensity required for future certification.

Hydrogen-rich firing has been considered to mitigate furnace emissions in Case 2, but application in large SMR heaters requires significant design modifications.

In contrast, ATR and POx configurations (Cases 4 to 8) offer higher reliability, simpler carbon capture, better scalability, and stronger long-term economic value despite higher initial capital.

Emerging low-carbon pathways

Catalytic methane pyrolysis offers a promising route to very low-carbon ammonia by generating solid carbon rather than carbon dioxide, eliminating capture and storage requirements. Although at pilot scale, integration of pyrolytic hydrogen into ammonia synthesis could lower carbon intensity near-term.

Catalytic methane pyrolysis converts methane to solid carbon and hydrogen without process-related carbon dioxide emissions. Each ton of ammonia yields approximately 0.54 tons of solid carbon potentially saleable into carbon black markets if quality permits. However, with global carbon black capacity near 15 million tons annually and slow demand growth, pyrolysis can support only limited ammonia production before market saturation.

Economics depend strongly on carbon black revenue; wider adoption requires new solid carbon applications. Key technical challenges include catalyst life, reactor performance, and stable high-temperature operation. The absence of process carbon dioxide makes pyrolysis attractive where carbon capture faces geographic or policy barriers.

Other emerging options include electrified reforming, which may complement ATR and POx designs as power grids decarbonise.

Conclusions

This assessment demonstrates that deep decarbonisation of ammonia production requires integrated reforming, high efficiency carbon capture, and strategic process design – not simply minimising initial capital cost.

Case 2 delivers lowest capital and operating costs but cannot achieve future certification requirements. Post combustion capture limits removal to 95%, while large solvent systems face degradation, corrosion, foaming, and high parasitic loads that reduce reliability and increase lifetime costs. At 3,500 t/d, both the SMR and capture systems approach practical limits. Hydrogen-rich firing would require complete heater redesign, making Case 2 unsuitable for ultra-low carbon intensity targets.

ATR based Cases 4 to 6 and POx based Cases 7 and 8 provide the robust pathway forward. They achieve greater than 98% carbon capture by concentrating CO2 in syngas, eliminate flue gas treatment complexity, and scale effectively to meet emerging certification standards. Overall carbon intensity will continue declining as power grids decarbonise, further reducing Scope 2 emissions.

Catalytic methane pyrolysis and electrified reforming offer long-term decarbonisation potential. Still, pyrolysis remains early in development, with no commercial references, and faces limited scalability unless new, higher volume carbon applications emerge.

Overall, technology selection is site-specific and requires a balanced assessment of cost, reliability, carbon intensity, and long-term value.