Sulphur 422 Jan-Feb 2026

28 January 2026

Neutralisation of heat stable salts – Part 2

AMINE SYSTEMS

Neutralisation of heat stable salts – Part 2

Joel Cantrell of Bryan Research & Engineering (BR&E) and Clay Jones of INEOS GAS/SPEC continue their review of neutralisation of heat stable salts. Part 2 focuses on how caustic (NaOH) affects amine chemistry and corrosion and the effects of adding too much NaOH.

NaOH effects on amine chemistry and corrosion

Simulation study

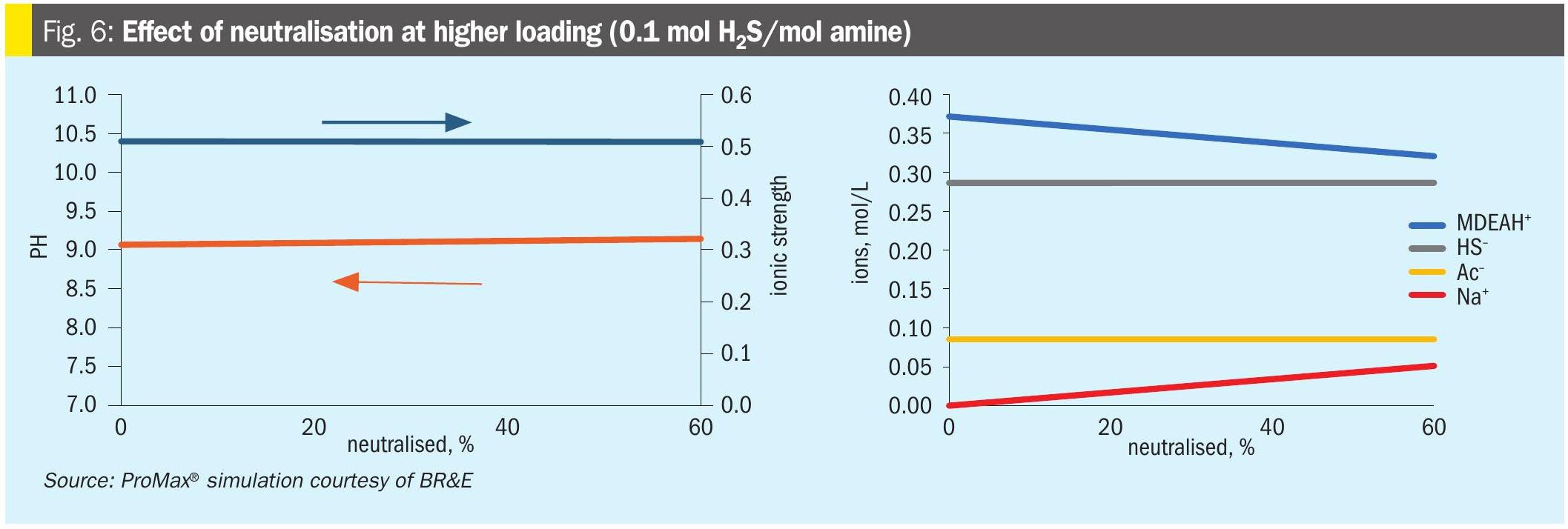

A ProMax® simulation study was used to investigate what happens to ionic speciation when NaOH is added to an amine solution with HSS. The example uses a 34 wt-% MDEA solution with acetate as a contaminant. To simplify the process, only H2S is considered as an acid gas.

More free amine, no change to ionic strength

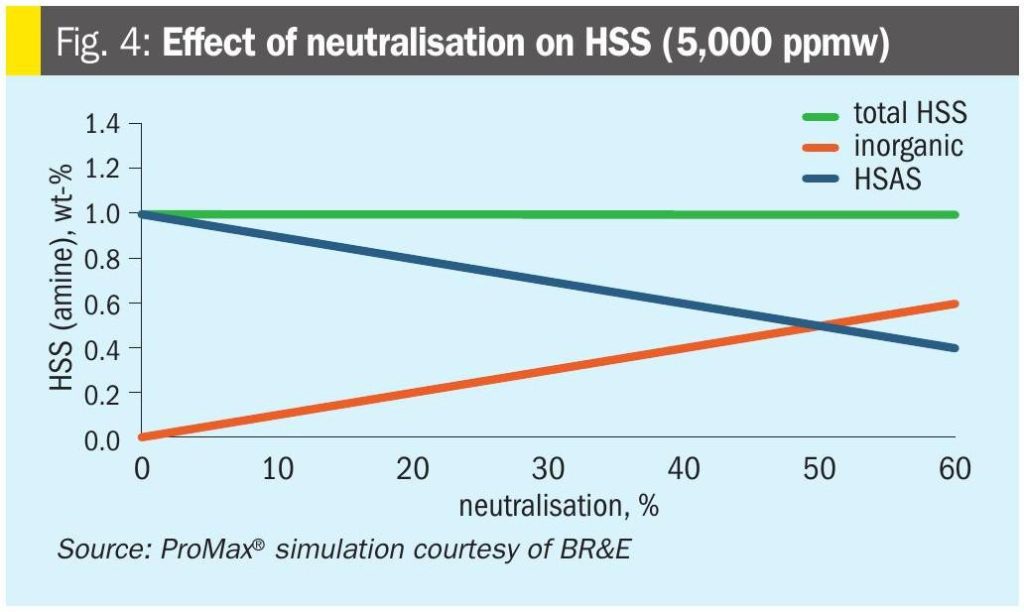

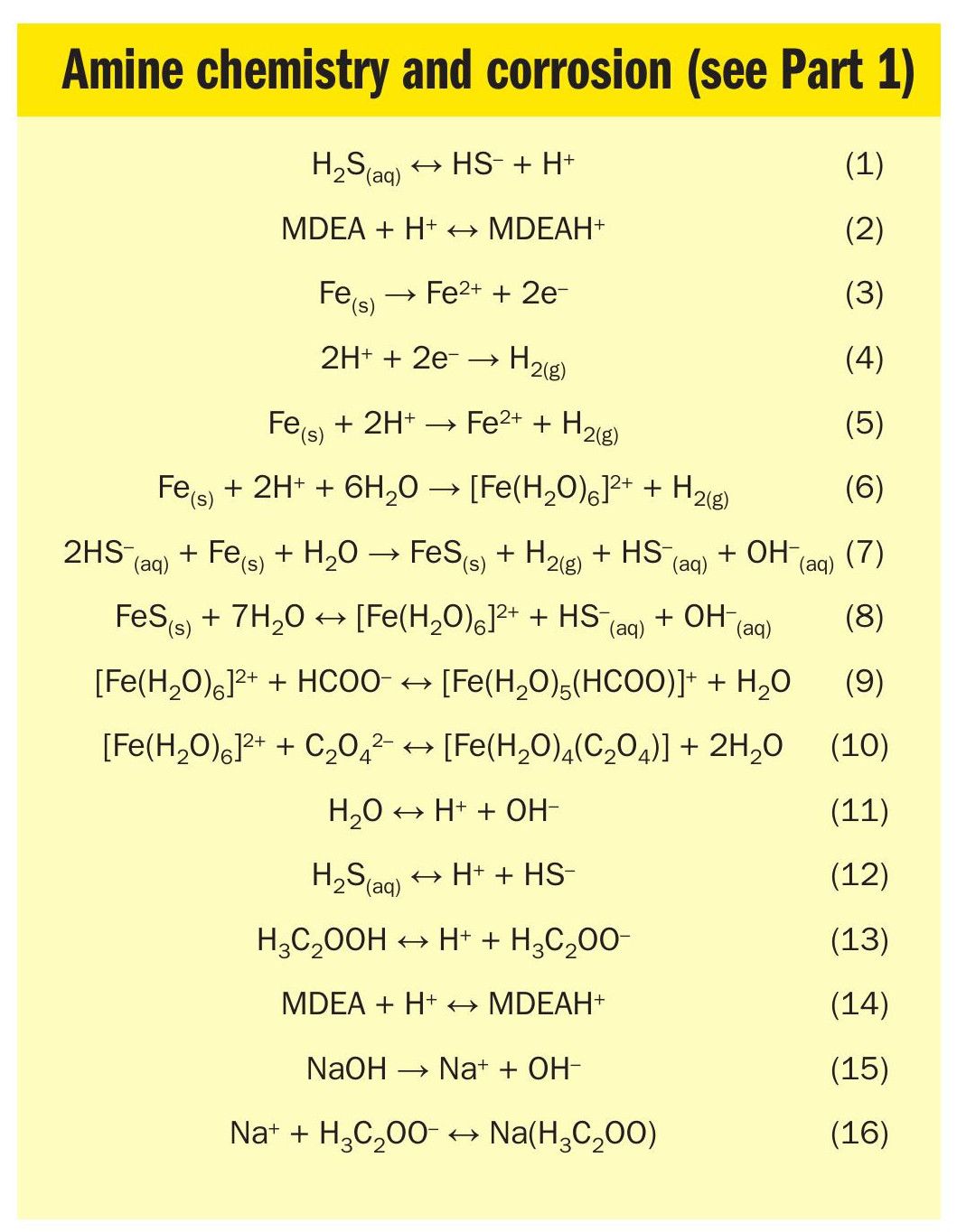

Fig. 4 shows the primary intended effect of neutralisation: Heat stable amine salts are converted to inorganic heat stable salts – even though total heat stable salt content is not changed.

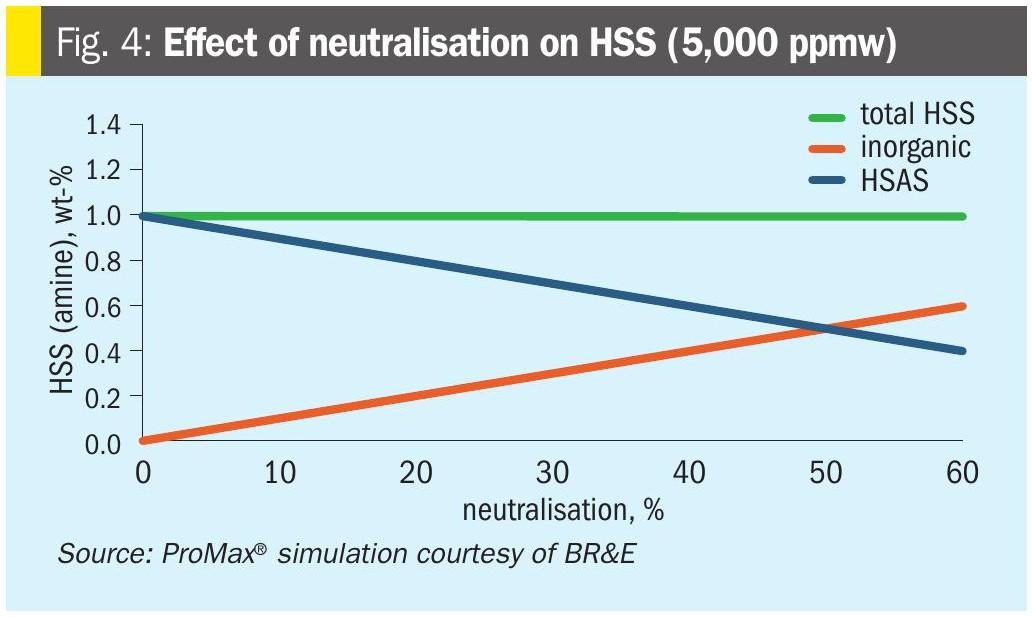

The simulation study was used to explore what changes are happening at the ionic level. As shown in Fig. 5, one clear and expected

effect of adding NaOH is to raise the pH of the amine solution. The shift in pH is due to NaOH supplying OH– anions to the solution, which consume H+ through equation 11.

Due to the common ion effect, the increasing pH also frees protonated amine molecules by shifting equation 14 to the left.

This gives us one of the uncontroversial benefits of neutralisation: It converts protonated amine (also called bound amine) into free amine, which restores some incremental capacity to hold acid gas.

An unexpected finding from the ProMax® study is that ionic strength does not change appreciably due to neutralisation, and therefore other properties that depend on ionic strength (electrical conductivity, activity of ions, etc.) should not be expected to change very much either. This makes sense upon reflection: As shown in Fig. 5, the net effect of adding NaOH is to convert MDEAH+ into Na+ , i.e., it changes one cation for another cation in a 1:1 swap without any net increase to the number of charged ions in solution. This simulation result is at odds with observations made in Reference 2 where adding NaOH to an HSS-laded amine solution resulted in higher conductivity in the lab. At this time, no explanation for this difference is offered – it could be an area for further investigation.

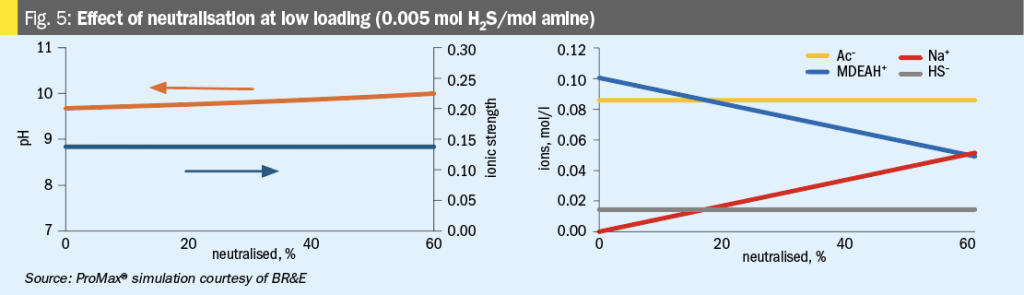

Fig. 6 shows the impact of neutralisation of a solution with the same HSS content, but higher loading (0.1 mol H2S/mol amine). The behaviour of Fig. 5 would be unchanged. However, at higher loading, the H2S dominates the ionic character of the solution, and the pH is essentially unaffected by neutralisation. Again, Na+ ions replace the MDEAH+ ions to provide an essentially unchanged ionic strength throughout the range of neutralisation.

Impact on corrosion rate

The effect of neutralisation on corrosion rate is not completely clear, with some evidence existing on both sides.

On one hand, lab work presented in Reference 7 shows that corrosion rate correlates with pH as shown in Fig. 1. This makes sense considering equation 6, which shows that iron corrosion requires a source of H+ ions, which are generally less available as pH increases. Notably, the experimental work in Reference 7 was done in the absence of H2S, so the protective influence of iron sulphide was not evaluated. Despite this fact, the data confirm that there is an acidic corrosion mechanism which would always be waiting to exert its influence any time fresh iron is exposed to the solution, e.g., when iron sulphide is removed by chemical solubility, flow-induced drag forces, or mechanical erosion.

Also, reactions between sodium and HSS anions, such as equation 16, are known to happen to some extent. For example, calculations done in Reference 9 suggest that caustic neutralisation might chemically bind approximately half of bicine anions. HSS anions which are partially bound to sodium cations will be less available to participate in the iron complexes which accelerate corrosion, i.e., such HSS anions will be less available to participate in reactions like equation 9 and equation 10.

Finally, there are numerous anecdotal stories of operating plants who report lower corrosion rates and longer amine filter life when they maintain controlled levels of neutralisation. Some of these plants have been following this practice for decades. Stories from the field are emphatically not the same as carefully collected data, but neither should they be rejected out of hand. There is a definite subset of our industry – professionals who operate real world process equipment year after year – which is convinced that neutralisation helps reduce corrosion.

On the other hand, the lab study in Reference 2 concludes that neutralising increases (not decreases) the overall corrosion rate in MDEA systems from 20 to 30 mpy before neutralising to 40 to 50 mpy after neutralising. Findings for DEA systems are less clear cut and may show reduced corrosion rate after neutralising. The authors of Reference 2 also emphasise that the best way to reduce HSS-related corrosion is to get rid of the HSS – a conclusion that bears repeating. Even at its best, neutralisation is a coping mechanism not a remedy. It can potentially extend the length of time between reclaiming or purging amine, but it does not remove HSS or other contaminants from the amine.

Higher lean loading

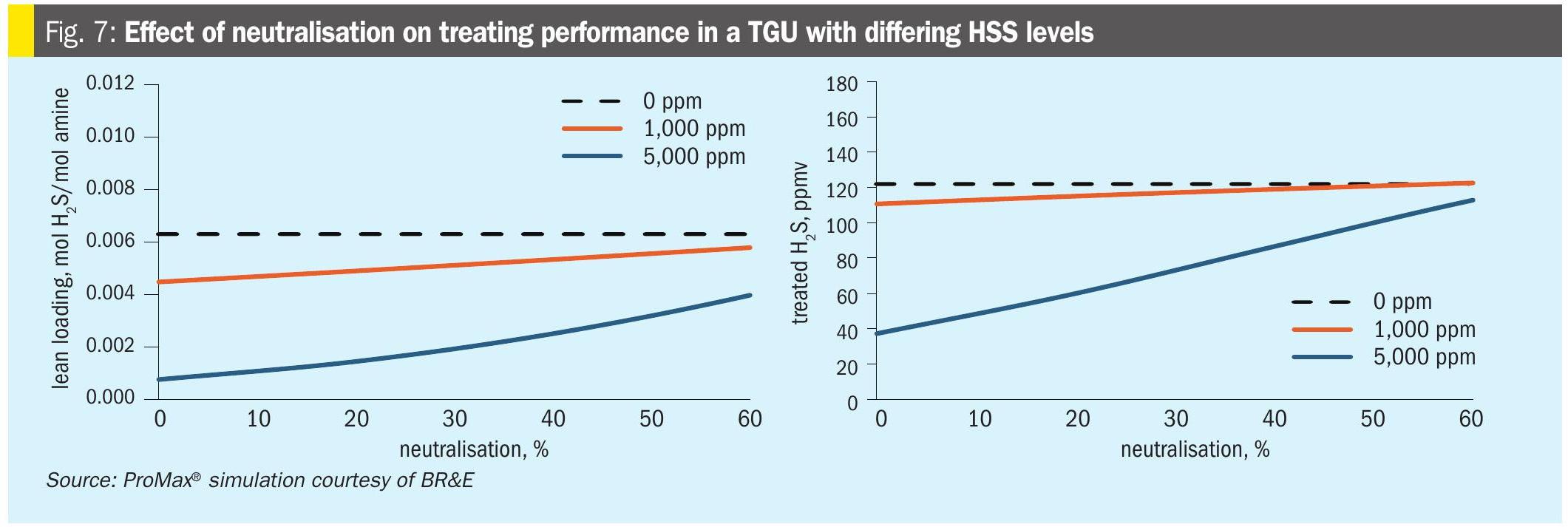

Another uncontroversial effect of adding NaOH is that it leads to higher lean loading. When HSS contaminants accumulate, they contribute additional H+ ions to the solution, which drives Equation 12 to the left, converting more of the dissolved H2S into its uncharged volatile molecular form, which has the net effect of making it easier to strip H2S to very low levels. This effect was previously introduced in Part 1. Fig. 7 shows the impact on a typical TGU of neutralisation at three different levels of HSS contamination. As the neutralisation increases, the beneficial effect of the HSS on lean loading and treated gas H2S is diminished. This represents a fixed reboiler duty. For the case of trying to hold lean loading constant, the reboiler duty would be increasing with increasing neutralisation.

Adding NaOH reverses this effect by supplying OH– ions that tend to consume H+ to make water by equation 11.

Numerous real world plant experiences with both intentional and accidental addition of NaOH to the amine have observed this increase in lean loading.

As long as the solution is not neutralised to 100% or higher, i.e. when the molar quantity of NaOH added is smaller than the quantity of acid equivalents from HSS anions, this effect will be limited to cancelling out the beneficial side-effect of HSS. We will soon see that the effect can become more severe if the solution is over-neutralised to approach or exceed 100%.

Lower soluble iron

In plant data, it is often observed that neutralising an amine solution leads to lower concentrations of soluble iron. The plant data sets below are examples.

Earlier we established two mechanisms whereby HSS anions increase the solubility of iron: i) by reducing the pH, which would affect the equilibrium of equation 3 through equation 8, and ii) by attaching to iron cations as ligands, which increase the solubility of iron through Equation 9 and Equation 10. Both of these HSS effects would be reversed by neutralising, thereby leading to a reduction in iron solubility.

For systems with CO2, another proposed mechanism for this effect was given in Reference 2 which noted that neutralisation raises the solution pH. Higher pH shifts the equilibrium of dissolved CO2, which primarily exists as bicarbonate HCO3–, to have a larger proportion in the form of carbonate CO3–2. The presence of carbonate and dissolved iron encourages the precipitation of iron carbonate.

Reduced volatility of acids in reboiler

Spooner and Costelow10 described a regenerator at risk of failure by corrosion due to very high levels of formate at 15,000 to 20,000 ppmw, vs typical max limit of 2,000 to 5,000 ppmw. To extend the service life of the regenerator vessel, they employed a suite of changes to mitigate further damage, one of which was caustic neutralisation. Caustic neutralisation was used in this case to trap volatile formic acid in the bulk amine liquid where it is less corrosive due to the presence of amine. To investigate this claim, a ProMax® simulation was created to roughly match the vapour phase formic acid profiles shown in the paper. The study was not meant to exactly mimic Reference 10, nor to critique the conclusions or methods there, but rather to investigate the claim through detailed analysis of simulation results. The simulated dewpoint liquid for the reboiler vapor was found to have a pH of 7.76 for the base case and

8.15 for the neutralised case. The difference was that neutralisation reduced the volatility of formic acid, as expected. This result shows a directional benefit for neutralisation in cases with severe formate contamination. For more typical levels of HSS contamination, there will be much less volatility of HSS acids, and therefore this effect will not be significant in most amine units – though it is a great trick to keep in mind for extraordinary circumstances.

Plant data

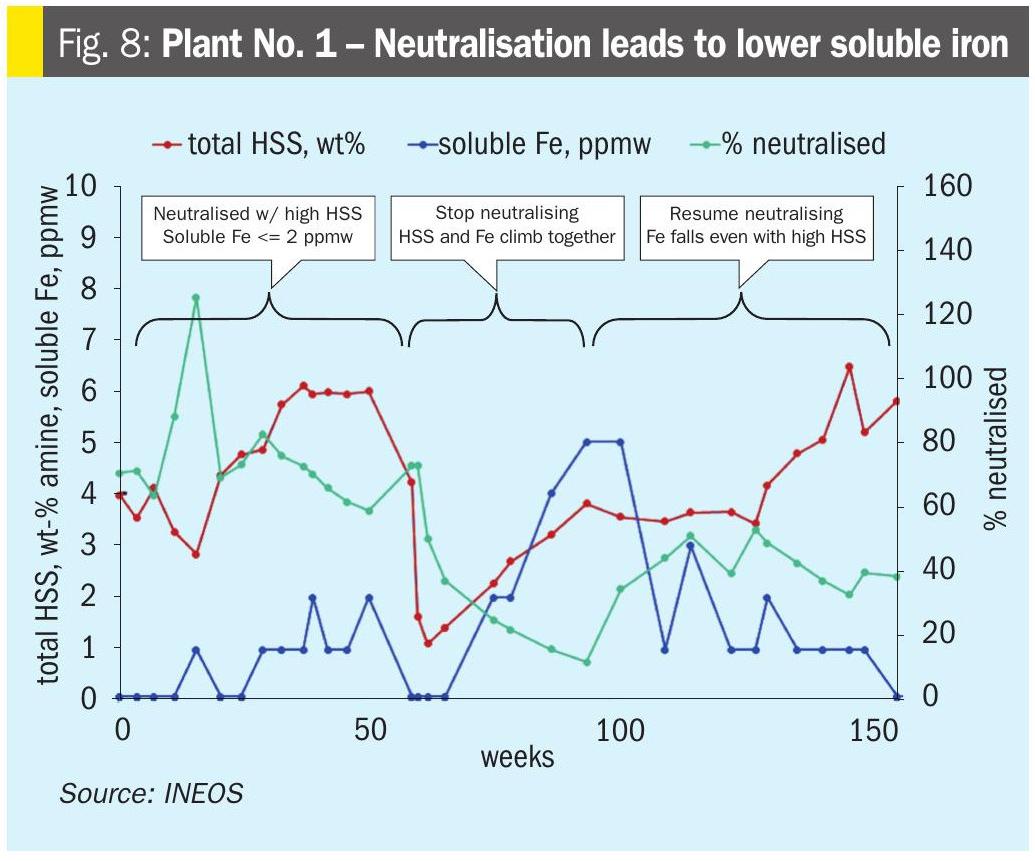

Plant No.1 – Neutralisation leads to lower soluble iron Data shown in Fig. 8 demonstrates a correlation between % neutralisation and soluble iron. Even when Total HSS are high, there is low soluble iron when neutralised. In this unit, HSS are predominantly formate and thiocyanate, which is typical for refinery service.

During the first time period, Total HSS are high at 3 to 6 wt-%, the amine is 60 to 80% neutralised, and soluble iron is low at ≤ 2 ppmw. At the end of this time period, the amine was reclaimed, which resulted in lower HSS and soluble iron.

In the second time period, HSS began to accumulate in the solvent, but the plant did not neutralise the salts. During this time, HSS climb to 3 to 4 wt-% and soluble iron climbs to 5 ppmw.

In the third and final time period, the plant resumes neutralising. As the plant comes up to 40 to 60% neutralised, the soluble iron again falls to ≤ 2 ppmw.

Plant data

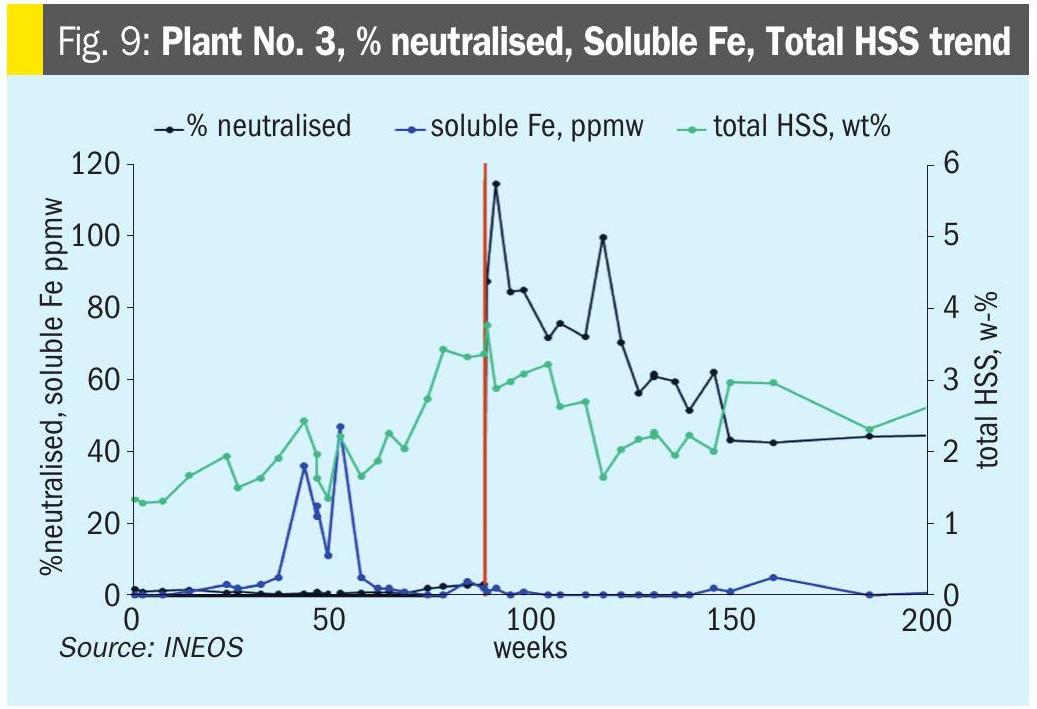

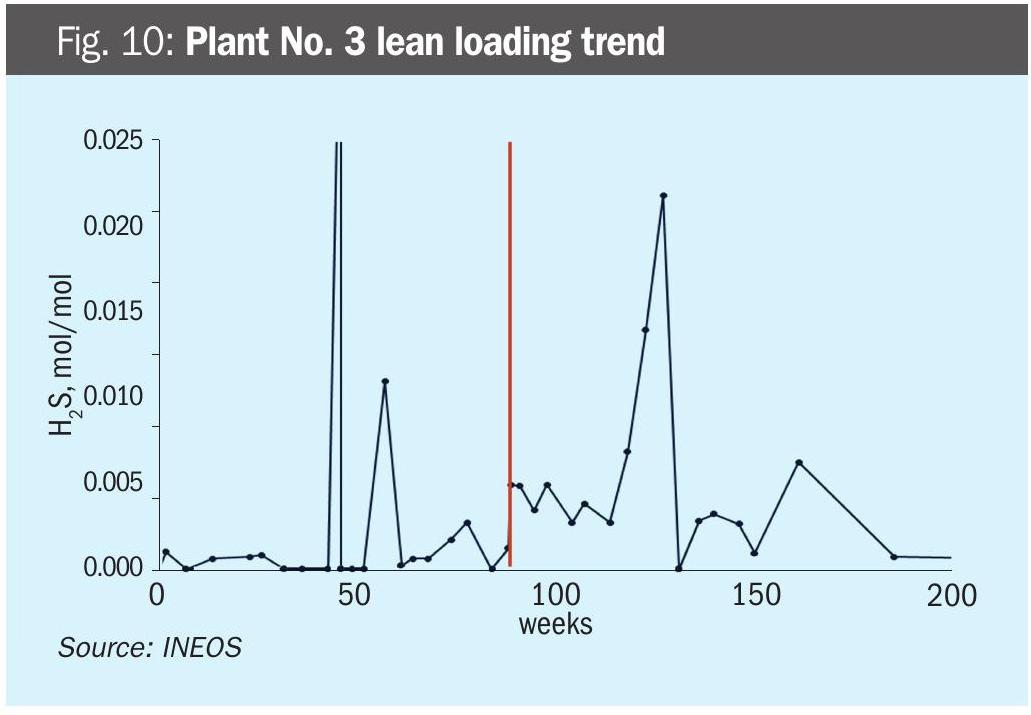

Plant No. 3 – Neutralisation leads to less corrosion and longer filter life (anecdotal) In this H2S and CO2 system, the plant reported experiencing corrosion failures and frequent filter changes. They added NaOH to reach 7,000 ppmw Na+ and 100% neutralised (Fig. 9). The plant reported fewer corrosion issues and longer filter life. There was a noticeable increase in lean loading (Fig. 10), but soluble metals did not have a clear response (Fig. 9).

This rather inconclusive example was included in the paper to represent a typical real-world case: plant personnel report a benefit for neutralising, but supporting data are thin.

Effects of adding too much NaOH

Simulation study

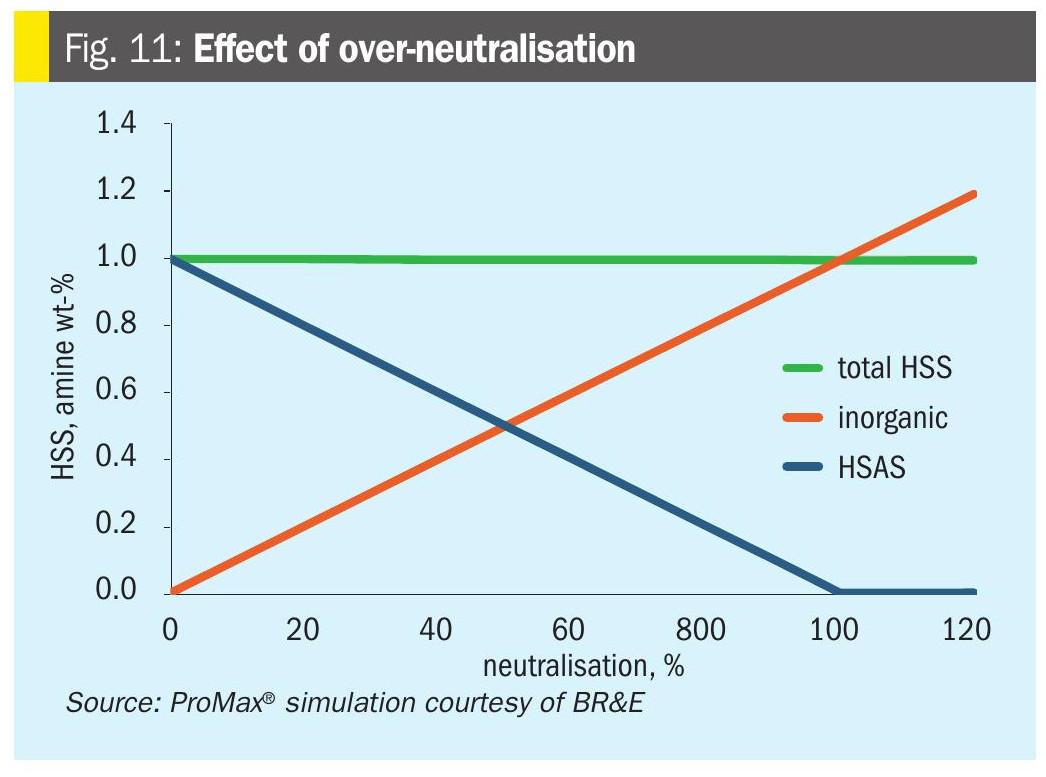

If some neutralisation is good, is more better? Not usually. Fig. 11 shows a ProMax® simulation HSS chart for the 34% MDEA system with 5,000 ppmw acetate, extended to 120% of neutralisation. Eventually the HSAS drops to zero, meaning that no amine is ‘bound’ as HSAS.

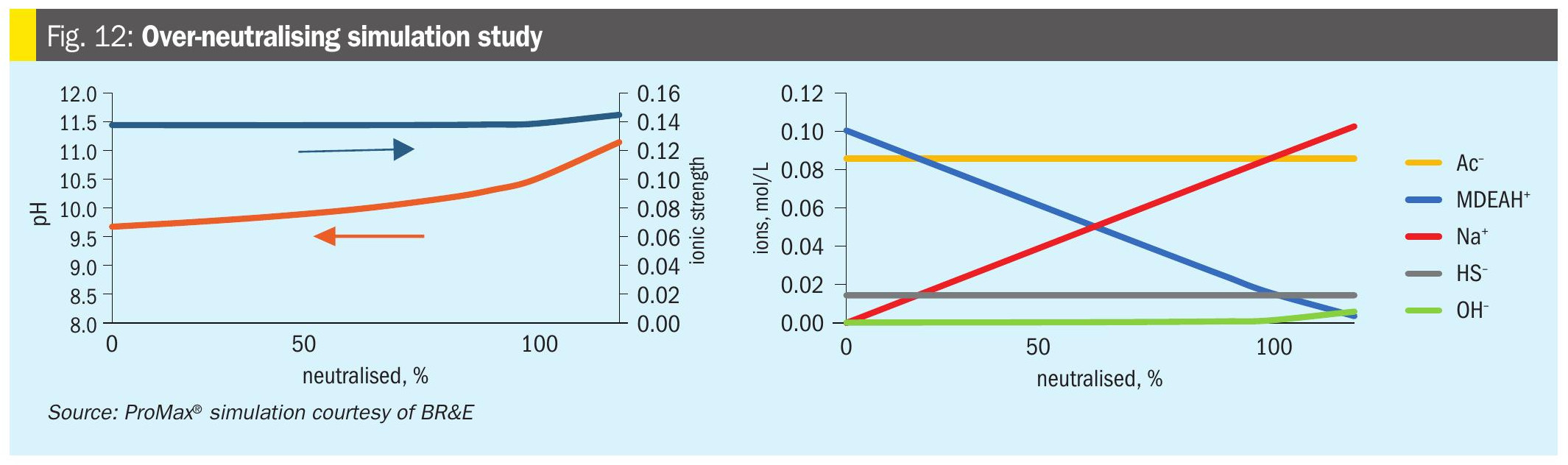

Fig. 12 explores what is going on with the chemistry for a lower H2S loading solution. As we continue to increase % neutralisation, the solution pH continues to rise and ultimately the ionic strength also begins to rise as more [OH–] ions are present. These effects would be expected to correlate with increasing conductivity and will directionally increase the risk of alkaline stress corrosion cracking. While the amine is technically ‘unbound’ from the HSS at 100% neutralised, the MDEAH+ does not completely disappear, even at 120% neutralisation, due to the presence of the HS– and OH–.

In the case of a more highly loaded solution, over-neutralisation does not change the ionic character of the system substantially. The HS– dominates relative to the acetate, so neutralisation only increases the pH by 0.1 and the ionic strength remains essentially unchanged.

Increased lean loading, potential for plugging

With respect to lean loading and potential for plugging, the trends which were explained above earlier are extended even further when too much NaOH is added. As the solvent approaches and exceeds 100% neutralised, the impact on lean loading becomes more pronounced. As the amount of excess NaOH increases, it begins to irreversibly trap H2S in solution as NaHS, which – thanks to the common ion effect and equation 12 – also affects the ability of the solvent to pick up additional H2S. Therefore, there is a further increased risk of more H2S slip through the absorber and inability to reliably hit treating targets. Note that the impact on treated gas is not always observed, depending on the operating regime of each amine contactor. The effect on lean loading is shown in the following plant data example.

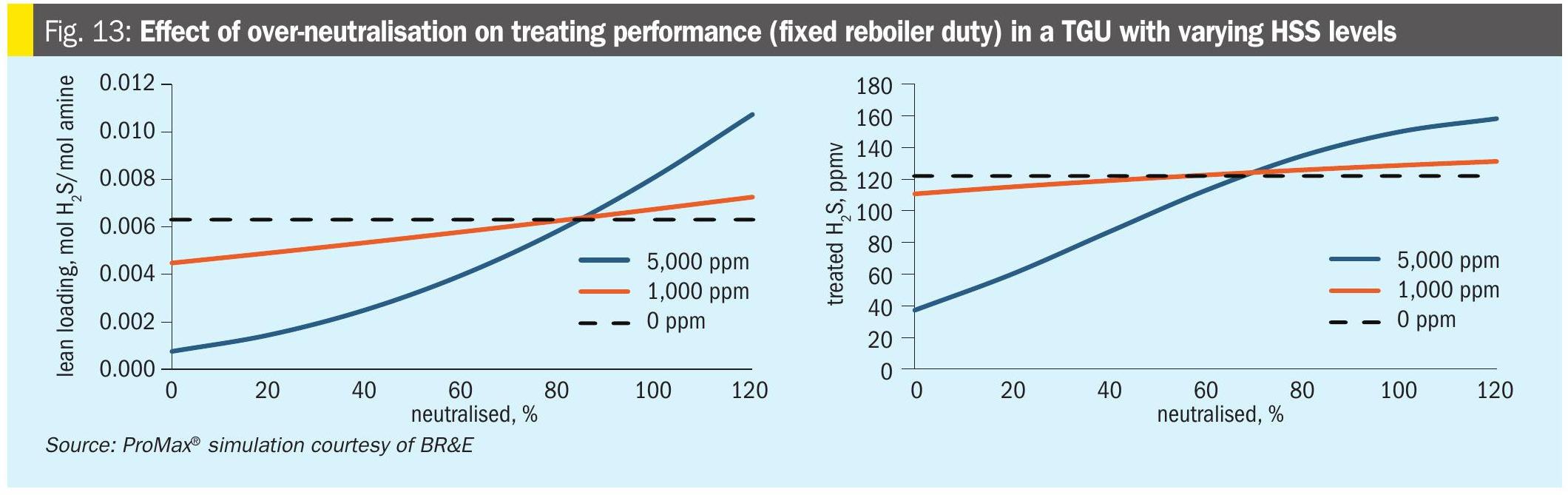

Fig. 13 shows the simulated impact of over-neutralisation on lean loading and treated gas H2S in a typical TGU. At roughly 85% neutralisation, the lean loading has returned to the level for the case without HSS. Above this point, continued neutralisation leads to further increases in lean loading and H2S in treated gas.

Potential risks of plugging also increase if a system is neutralised beyond 100%. Precipitates could include sodium salts (e.g., NaHCO3, Na2 CO3), iron salts (e.g., FeCO3), or corrosion products like FeS which may tend to sluff off during neutralisation2. INEOS has direct experience with a refinery which over-neutralised to > 7000 ppmw Na and > 100% HSAS neutralised. This plant experienced severe plugging in their carbon bed which took considerable effort to clean out.

Plant data

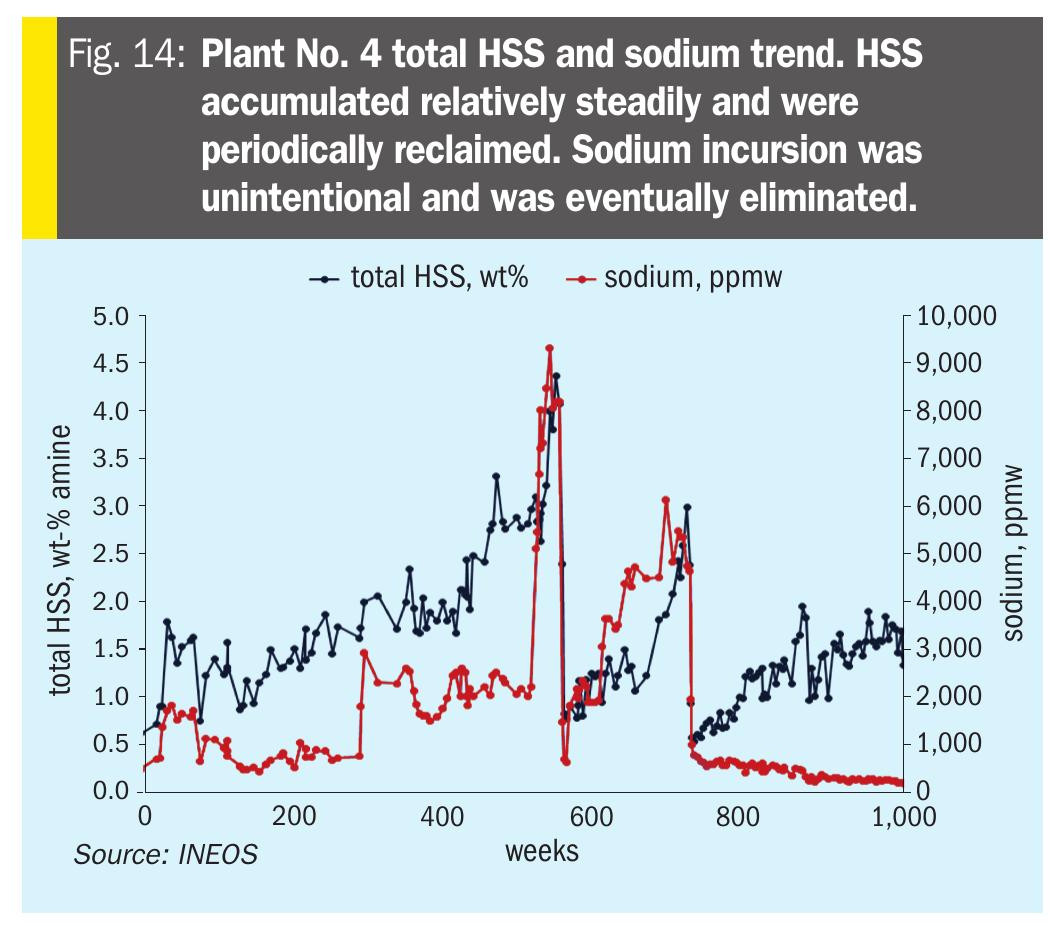

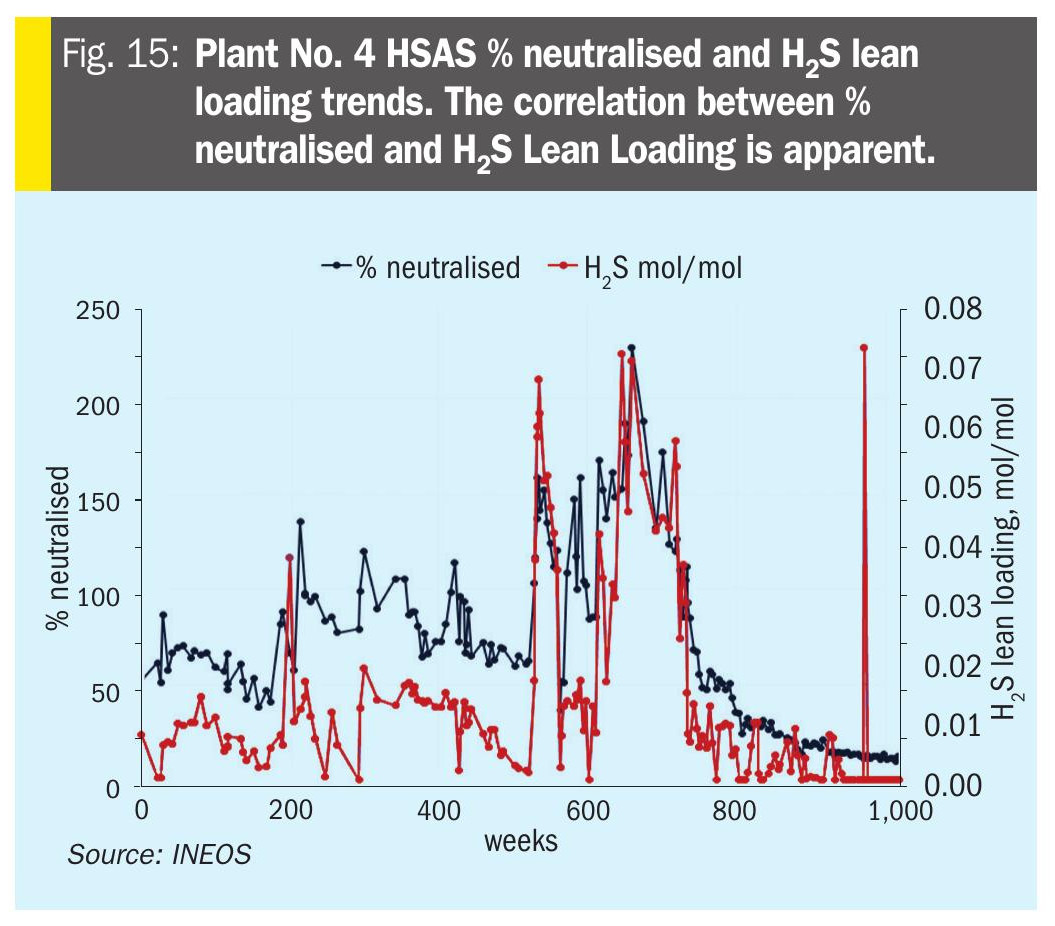

Plant No. 4 – Over-neutralisation leads to higher lean loadings This refinery ARU had unintentional Na+ and K+ incursion (Fig. 14) leading to > 100% neutralised solvent. The issue was eventually resolved.

Soluble metals were low during the entire time. There was a clear correlation between over-neutralising and higher lean loadings (Fig. 15).

Conclusion

Neutralisation is not a panacea for all problems related to heat stable salts, but it continues to be practiced in industry with positive results. It would also be most advised for systems that are well-monitored with personnel who know their systems and the phenomenon of acid-base chemistry and its ramifications.

Benefits of neutralisation:

- restores amine’s capacity for acid gas pickup;

- lowers corrosion rate (not unanimously agreed);

- can extend time until purge or reclaim is needed;

- low cost, quick to implement, uses materials that are often on-site already.

Potential drawbacks of neutralisation:

- total HSS level does not change, HSS anions are not removed;

- injecting too much or too quickly can lead to plugging and increased risk of alkaline stress corrosion cracking;

- system now has Inorganic HSS to deal with;

- can increase lean loading which can sometimes hurt acid gas pickup (this is not unique to neutralisation – it can happen with purge and reclaim too).

References