Fertilizer International 530 Jan-Feb 2026

23 January 2026

Bringing balance to blueberries: the power of nitrate and iodine

MICRONUTRIENTS & SPECIALTY POTASH

Bringing balance to blueberries: the power of nitrate and iodine

Blueberry cultivation still holds many secrets and unlocking these requires nutrient strategies that are attuned to every growing region, cultivar, and substrate. Supplying nitrate – a valuable nitrogen source and hormone ‘signalling’ molecule – in combination with the beneficial nutrient iodine has been shown to deliver measurable yield and quality improvements for growers. Katja Hora, SQM’s Research Manager, Iodine Plant Nutrition, outlines the evidence.

The economic rise of blueberries (Vaccinium sp.) has been extraordinary. They may be familiar as an elegant finishing touch on your dessert after a festive dinner in a wintery European city. Yet many don’t realise that these berries will have travelled much further than most diners to reach the restaurant.

In fact, the pursuit by retailers and restaurateurs of a year-round supply of this global ‘superfood’ has sparked growth in blueberry production in horticultural regions across the world. This expansion opens the door to developing advanced nutrition guidance for blueberry growers, especially in places where the local soils and climate are not naturally suited to this crop.

A new arrival on our plates

The story of commercial blueberries is relatively young. The first domesticated high-bush blueberry harvests were recorded in the early 20th century, driven by the desire to make use of the sandy, acidic soils of New Jersey’s pine barrens1 .

While few other crops could grow on these soils, early studies of wild Vaccinium blueberry species revealed just how uniquely adapted these plants were to nitrogen-poor, acidic environments (with ideal soils between pH 4.0 and 5.5). As blueberry cultivation spread to new regions, growers encountered soils richer in clay, more neutral or alkaline in pH, and far outside the crop’s natural comfort zone.

These conditions presented one of the central challenges still faced by today’s commercial blueberry growers: how to optimise nutrient uptake in environments these soft fruit bushes did not evolve to handle. In particular, blueberries possess an extremely fine, fibrous root system and – unlike many crops – they lack root hairs. This trait is believed to reflect their evolutionary reliance on mycorrhizal partnerships in acidic, nutrient poor native soils.

Early agronomists observed that blueberries seemed to prefer ammonium (NH4+) over nitrate (NO3–), especially in high-pH soils where ammonium helped acidify the rhizosphere. Over time, extension literature distilled this into a widely adopted rule of thumb: use ammonium, avoid nitrate. But is this really true?

Modern research, in fact, paints a far more nuanced picture2 . Recent studies show clearly that blueberries can absorb and assimilate nitrate as well as ammonium. Nitric nitrogen can be converted into amino acids in the roots, and nitrogen can move throughout the plant as amino acids, nitrate, or ammonium.

Even more importantly, blueberry plants often perform best when both forms of nitrogen are supplied together.

A mix of NH4+ and NO3– in a 1:1 ratio in a nutrient solution, for instance, has been shown to result in the highest shoot dry weight in blueberries, more flowers and more soluble sugar and starch in leaves, compared to unequal ratios3,4. This realisation opens the door to far more flexible, balanced, and adaptable fertilization strategies – this being especially promising news for growers working outside traditional blueberry soils.

Nitrate, besides being a valuable nitrogen source for plants, is also a ‘signalling’ molecule. It plays a key role in shaping plant hormone balance, by stimulating the expression of genes involved in producing zeatin-type cytokinins, for example5. Similar to their role in other crop species, cytokinins are central to shoot growth and tissue differentiation in blueberry6. Understanding how NO3– influences hormone balance in blueberries is therefore well worth exploring.

Nutrients for quality

Consumers, meanwhile, expect blueberries on supermarkets shelves and dining plates to remain sweet, firm, and visually appealing, even after long-distance transport. Potassium is essential for sugar translocation, while calcium plays a central role in fruit texture and shelf-life. This is, again, where nitrate plays an important supporting role by improving accumulation of K+ and Ca2+ in blueberry4.

As in many other fruits, most calcium enters blueberries during early development. It is well recognised that this is a challenge not easily solved by adding Ca2+ in the nutrient solution. Agronomists are still exploring new ways to enhance calcium uptake and movement to secure longer shelf-life and better fruit integrity during retail.

A newcomer to the discussion on improving calcium uptake is iodine. This halogen is now recognised as a ‘beneficial nutrient’ by ISO standard 8157 (2022)7 using the following definition:

“Elements, other than those defined as primary nutrient element, secondary nutrient element or micronutrients, that are known to be needed for plant growth and development or for the quality attributes of the plant product, of a given plant species, grown in its natural or cultivated environment. Known beneficial nutrient elements include Si, Se, I, Co, Na, Al, and others as demonstrated.”

The benefits of iodine relate to its capacity to bind covalently to plant enzymes that are essential for photosynthesis, assimilation and stress mitigation. Notably, iodine seems to be involved in the sensitive, calcium-dependent signalling process that determines the ability of plants to react to environmental stress.

“European findings highlight the potential of beneficial nutrients such as iodine to fine-tune nutrient programmes and help fruit plants respond to shifting climate conditions.”

Across Europe, agronomic studies have now demonstrated the effect of iodine on calcium translocation in tomato fruit. In the Netherlands, in plants where iodine was applied during fertilization, round tomato showed higher calcium levels following a series of summer heatwaves. This suggests that the presence of iodine during extreme weather is influencing nutrient movement during fruit development in ways we are only beginning to understand.

In Spain, meanwhile, researchers observed elevated calcium concentrations in the fruit and leaves of cherry tomatoes grown during the darker, colder months of the season.

These European findings highlight the potential of beneficial nutrients such as iodine to fine-tune nutrient programmes and help fruit plants respond to shifting climate conditions.

Improving growth, yield and resilience

With this in mind, researchers are looking to improve fertilizer strategies for blueberries, with a focus on two promising elements: nitrate and iodine. This includes a recent two-year randomised complete block (RCB) trial carried out in Poland on soil-grown ‘Bluecrop’ bushes, originally transplanted in 2006 and inoculated with mycorrhizae.

These mature, commercially productive blueberry plants provided an ideal setting to evaluate how subtle but strategic nutritional adjustments could translate into better crop growth, yield, and resilience. The Polish trial explored three key improvements to the prevailing local practice:

• Enhancing acidification of the drip solution by replacing monoammonium phosphate (MAP) with urea phosphate as the phosphorus source. This should create more favourable rhizosphere pH for better nutrient availability.

• Rebalancing the nitrogen ratio by increasing the proportion of NO3– from 22% to 56% of total N. This was accomplished by shifting from potassium sulphate (SOP, K2SO4) to potassium nitrate (NOP, KNO3) as the primary K source. The aim was to support stronger nutrient uptake and fruit quality and prevent accumulation of excess sulphate in the root zone.

• Introducing iodine into the nutrient solution in proportion to the applied KNO3, with the aim of strengthening root development, improving fruit calcium and boosting plant resilience to abiotic stress.

By embracing new scientific insights and incorporating these into the reality of commercial fruit production, these refinements offer a forward-looking approach to blueberry nutrition.

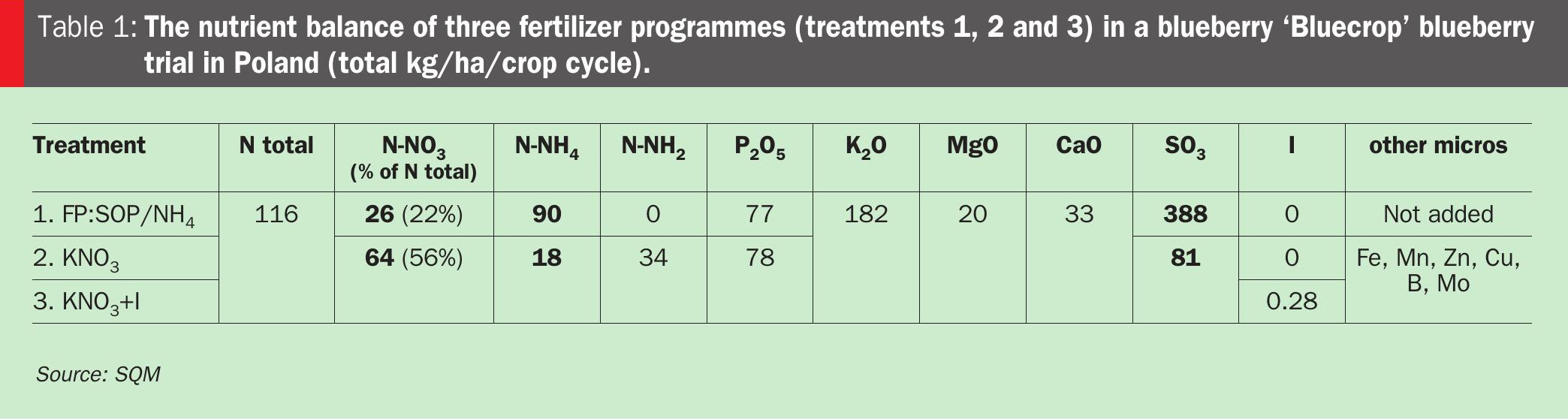

The following three fertilizer programmes (treatments 1, 2 and 3) were tested in the two-year Polish trial (Table 1):

• Treatment 1: Farm practice with application of potassium sulphate (SOP) with an ammonium nitrogen source.

• Treatment 2: Application of potassium nitrate (NOP) plus micronutrients (Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu, B, Mo).

• Treatment 3: Application of NOP and iodine (SQM Ultrasol®ine) plus micronutrients (Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu, B, Mo).

In the first year, the total season berry yield was a stunning 29% and 36% higher in treatments 2 and 3, respectively, compared to the farm practice yield of 16 t/ha. In the second year the same plants still gave a higher yield: being 4% and 12% higher in treatments 2 and 3, respectively, compared to the farm practice yield of 16 t/ha. The benefit compared to the farm practice was due to a statistically significant higher number of fruits per plant.

Moreover, the berries showed a better shelf life during 6 days of cold-room storage followed by 10 days of room temperature storage. In the first year, for example, only 22-24% of the berries displayed grey mould in treatments 2 and 3 compared to 34% mouldy fruit found with the farm practice. In the second year, fruit was 21 percentage points less mouldy using treatment 3 (SQM Ultrasol®ine with iodine) compared to 57% mouldy fruit found using farm practice.

‘Spectacular’ hydroponic results

High density hydroponic cultivation methods, by taking blueberries out of the soil, can eliminate the challenges and complication of blueberry cultivation on unsuitable soil types. This can deliver quite spectacular increases in yield potential.

While only about 5% of the total blueberry hectares in Peru were grown hydroponically (‘in pots’) in 2016, this share had grown to 19% by 2022. The cocoa-fibre based substrates used in Peru offer an excellent growing medium that can realise the high production potential of modern cultivars. Nutrients can also be regulated hydroponically at a precise pH and balanced to optimally match the ancestral root zone solution of blueberries. Additionally, hydroponic technology, if managed well, can reduce nitrogen leaching and improve water use efficiency.

It is standard practice to combine the application of nitric nitrogen with ammonium nitrogen in substrate-grown blueberries in both Peru and Mexico. The addition of iodine with potassium nitrate has also been evaluated.

An on-farm trial was carried out in Mexico on blueberries (var. Biloxi) grown in a cocoa-chip substrate. The addition of iodine to the nutrient solution (9.5 Meq./L NO3– vs 4 Meq./L NH4+) resulted in 1 degree C Brix increase (from 6.1 to 7.1) and extra fruit calcium (1.2 mg/100 g) in the tunnels, where this was applied with potassium nitrate (SQM Ultrasol® ine).

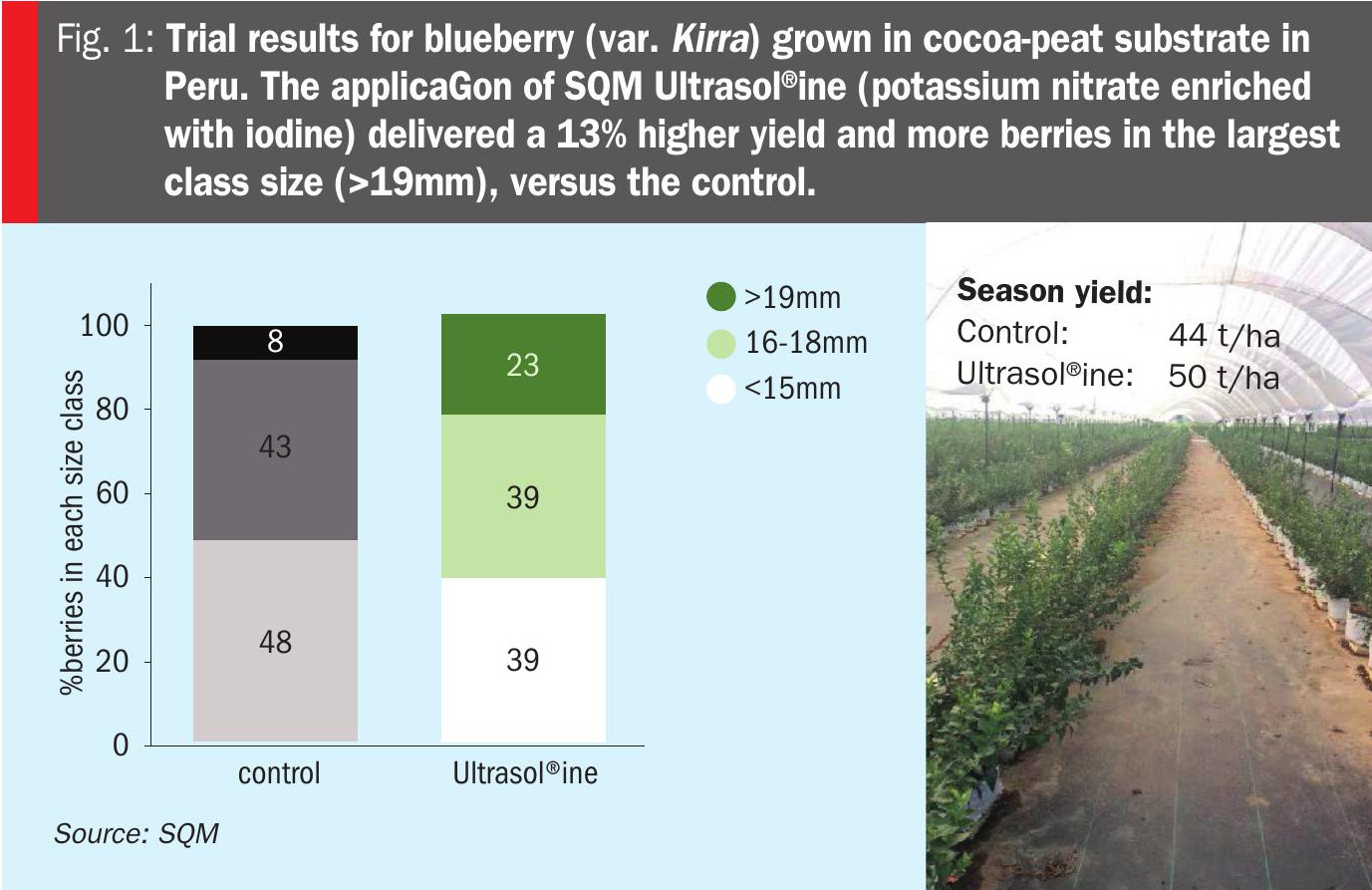

Highly positive results were also recorded in a trial on blueberry (var. Kirra) grown in cocoa-peat substrate in Peru. The use of iodine with potassium nitrate (SQM Ultrasol® ine) in a nutrient solution delivered a 13% yield increase, as well as bigger berries with more in the largest >19 mm size class (Figure 1).

Summing up

Blueberry cultivation still holds many secrets and unlocking these requires nutrient strategies that are attuned to every growing region, cultivar and substrate. In practice, that means leaving behind old beliefs and approaching blueberry crop nutrition with curiosity, innovation, and an open mind. The rewards? Consistently delicious berries that will delight consumers season after season.

References