Sulphur 422 Jan-Feb 2026

28 January 2026

Zero emission sulphuric acid production

SULPHURIC ACID PLANT DESIGN

Zero emission sulphuric acid production

Recalibrate™ has developed a next generation sulphur burning plant to produce sulphuric acid with ultralow SO2 and zero NOx emissions, designed to derisk the permitting process and increase speed to market for new sulphuric acid plants. In addition, the proprietary process minimises the added capital cost and operational expenses typically associated with pollution control strategies.

Sulphuric acid production maintains its position as one of the most produced chemicals in the world. With an installed base of over 750 units worldwide, these plants process a variety of sulphur sources including solid sulphur (S), metallurgical off gas (MET), hydrogen sulphide (H2S), and spent acid (SAR) to produce over 300 million tonnes of sulphuric acid (H2SO4) annually. Sulphuric acid is used in large industries critical to human growth, including: making fertilizer to grow our food;

- mining metals such as copper, nickel, and lithium critical to making everyday items;

- making steel and other materials used to build our buildings;

- making silicon chips that are the foundation for computers and AI.

As demand grows for these items critical to global infrastructure, demand for sulphuric acid must grow with it.

Regulatory standards challenge new plants

The recent economic climate and the impact of government regulations have caused regional differences in how acid producers conduct operations while staying competitive under new emission standards. Building a new sulphuric acid plant in most of the world has become a formidable challenge. For decades, few new plants have been constructed in the United States. The last large sulphuric acid plant in the US was for fertilizer production and was completed in 2010. A new wave of mining, semiconductor, and re-industrialisation projects is now driving demand for domestic sulphuric acid capacity. From lithium extraction for EV batteries to rare earth processing, semiconductor manufacturing, and fertilizer expansion, industry players need new acid plants quickly but face stringent emissions regulations and lengthy permitting processes that delay and often derail projects.

Current information from industry and environmental consulting firms indicates five to ten years for application approval times. These delays have a profound financial impact: project returns (IRR) can drop by 30% to 50% before production even begins, eroding project value (NPV) by up to 70% compared to initial forecasts.

As an example, the Rosemont Copper Mine in Arizona lost an estimated $3 billion in value after eight years of permitting delays. Certain project components face even greater regulatory challenges. Permitting for sulphuric acid production facilities is known to be particularly challenging.

Learning from the past

Understanding the past can be an important way to understand our future. The US has a rich history with sulphuric acid and shaped many of the technologies and standards used today around the world.

Ducktown Sulphur, Copper and Iron Company

The need for regulatory oversight arose from the manufacturing practices of the 1800s and 1900s where industrial off gases were directly emitted to atmosphere. One of the most well-known cases was the copper smelting operations of the Ducktown Tennessee basin by the Duck-town Sulphur, Copper and Iron Company (DCS&I, 1890-1936, see below).

DCS&I operated an open-roast heap smelting process whereby large quantities of crushed copper ore containing chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), chalcocite (Cu2S) and covellite (CuS) were piled onto a bed of combustible wood soaked in fuel oil. The company would ignite the bed, leaving it to burn for several weeks to drive off the sulphur as sulphur dioxide SO2, leaving a concentrated ore for further processing.

SO2 released by heap smelting, ~80,000 ppm, would react with water in the atmosphere to form acid rain that devastated the surrounding ecology. Following the US Supreme Court ruling in Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co (1907), DCS&I immediately implemented technology to capture and convert SO2 vapour into liquid sulphuric acid. The sulphuric acid stream quickly became a major co-product and eventually influenced the decision to restructure the Ducktown Sulphur, Copper and Iron Company into Ducktown Chemical and Iron Company (DC&I) in 1925. DC&I went on to pioneer the advancement of wet scrubbing, leading to technologies still in use today.

How the industry navigated new regulatory standards in the US

The next regulatory evolution was the implementation of the US Clean Air Act which established New Source Performance Standards (NSPS), capping SO2 emissions at 4 lb per ton of acid produced (approximately 2 kg/t) and acid mist at 0.15 lb/ton. These limits, equivalent to roughly 99.5% sulphur conversion efficiency, were the baseline that all new plants had to meet. In response, the acid industry adopted the double contact double absorption (DCDA) process commercialised in the 1960s and 1970s. The DCDA process uses four reaction beds to achieve the target 99.5% conversion rate. This process was designed to re-route ~2-3% unconverted SO2 gas from the converter (bed 3) through a new interpass absorber tower to remove most of the sulphur trioxide (SO3) as H2SO4. Gas exiting the interpass absorber would be sent back to the converter (bed 4) at conditions far from equilibrium to reach an overall SO2 conversion approaching 99.5%. Today companies that operate in regulated nations have adopted the DCDA process as standard technology; however, this decision comes with increased capital and operational costs from the second absorption tower and supporting equipment. Following the US Clean Air Act, regulators further increased standards though two additional enhancements: (1) the introduction of Best Achievable Control Technology (BACT) criteria, and (2) the ability of US State environmental agencies to enforce stricter limits than the federal NSPS regulation. Under the Clean Air Act’s amendments, BACT means a new plant can be required to hit the lowest emission level “economically demonstrated” anywhere in the industry. In response, many US States have set permit limits well below the federal 4 lb/ton SO2 standard to protect local air quality. While the federal SO2 limit has not changed in over 50 years, meeting only that standard today would fall woefully short of what US state regulators expect.

Improved catalyst to meet lower US state emissions standards

While federal law sets the floor, US states like North Carolina and Nevada have effectively set a higher bar through their permitting. North Carolina’s regulators allowed the large Aurora, NC sulphuric acid plant to be built on the condition it use advanced catalyst to cut SO2 emissions well below 4 lb/ton. The acid industry responded with subsequent enhancements to the DCDA process with the introduction of higher activity catalyst compositions.

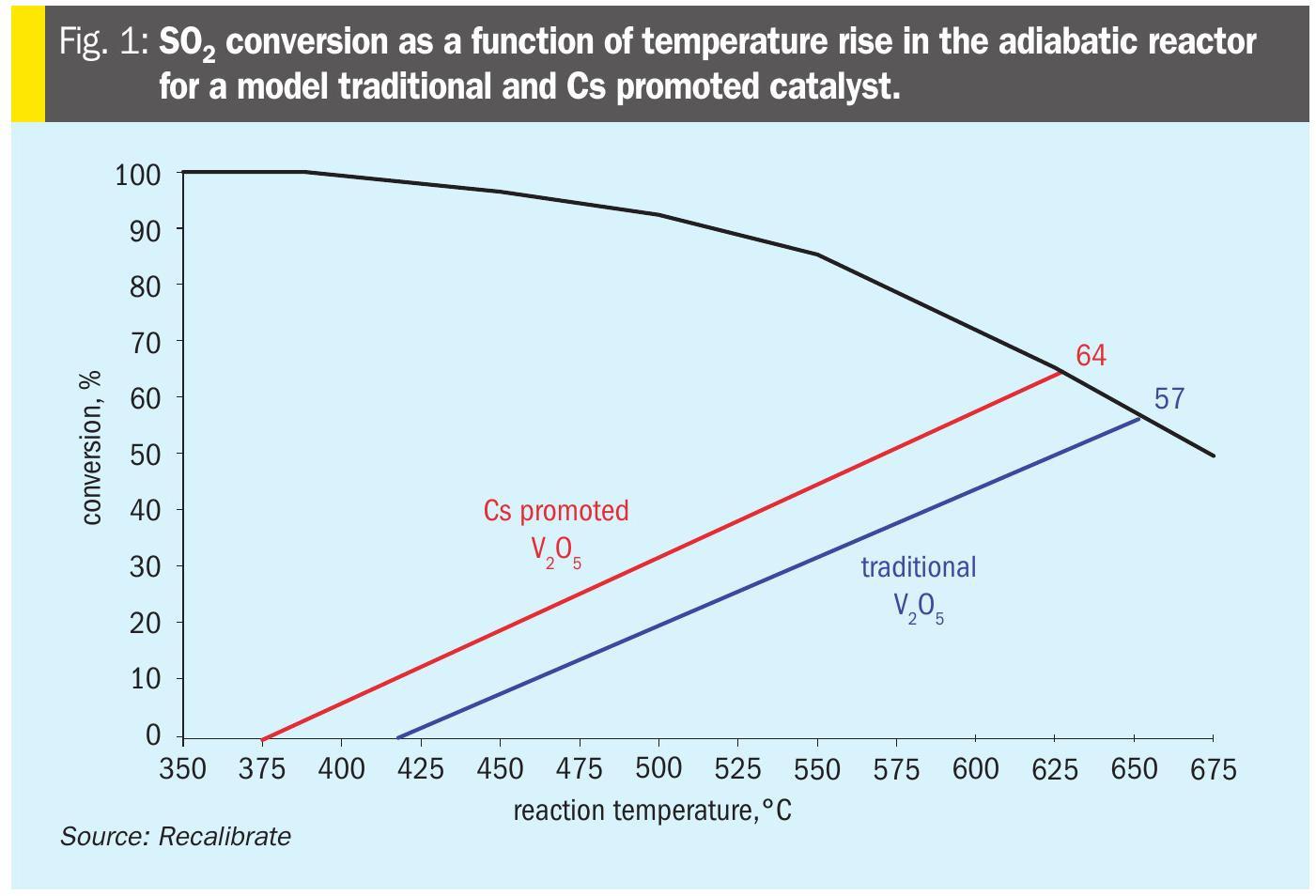

Here caesium (Cs) and other proprietary elements are added to the vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) base catalyst to lower the starting temperature for a sustained reaction by ~40-60°C. Because the SO2 oxidation releases heat and the reaction is limited at high temperature, this lower starting temperature enables more SO2 to be consumed per bed. For example, a caesium promoted catalyst would reach 64% SO2 conversion in the first pass where the previous generation catalyst would only reach 57% conversion (see Fig. 1). These catalysts enable modern plants to obtain conversions as high as 99.7% SO2.

Adding equipment for even lower emissions

In Nevada, the new Thacker Pass DCDA acid plant had to include a tail-gas scrubber unit to achieve SO2 emissions far under the federal limit. For highly regulated environments, tail gas scrubbers are the last line of defence for meeting stringent emission requirements and have been selected as a lower cost alternative to retrofitting single absorption plants with double absorption technology. They are also used in regulatory environments where emissions must be tightly controlled during abnormal plant operations such as upsets, start-ups, or in cases where high SO2 feed gas compositions must be processed. Tail gas scrubbers are offered in several variations whose selection depends on the plant operator’s tolerance for capital costs, operational expenses, and operability. Ultimately, tail gas scrubbing does not eliminate waste SO2, it only transfers a gaseous pollutant into a liquid or solid stream that must be treated appropriately. For a 1,000 t/d acid plant, caustic costs for the tail gas scrubber could exceed $600,000 per year. This is equivalent to $30 million over the life of a 50-year plant.

Case studies

In the following section three modern US case studies are detailed to illustrate the role of environmental regulation on acid plant construction, operation, and the pollution control technology owners choose to adopt.

Freeport McMoRan

The earliest modern acid plant construction project took place at the Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Mine in Safford, (AZ) between 2007 and 2011. The $150 million project was implemented on remote privately held land ~250 miles east of Phoenix AZ. This facility burns elemental sulphur to supply 1,250 t/d acid for leaching operations and produces power that enables the site to run completely isolated from outside sources. Peroxide tail gas scrubbing was selected early in the design process to target SO2 levels below 20 ppm and permitting was completed between 2007 and 2009. Two years is a remarkably fast permit time and a testament to what is possible when operators select BACT and are supported by regulators to implement that technology. The site continues to operate and has upgraded its acid capacity to 1,550 t/d as of this writing.

Nutrien Aurora

Near the end of the Freeport project, Nutrien Aurora, NC, formerly Potash Corp of Saskatchewan (PCS), was beginning work to replace its No. 3 and 4 sulphur burning units which were nearing the end of their ~40-year lifetime. The new No. 7 plant was planned to produce 4,500 t/d of acid for downstream manufacturing of phosphate fertilizer and carbon free power for the grid. Like the Freeport facility, Nutrien also chose to operate BACT in the form of caesium (Cs) promoted catalysts and DCDA to reach emission levels below federal and state regulation. Project permitting was simplified due to the site having existing acid plants and the project resulting in a net reduction in total emissions. The No. 3 and 4 plants relied on less efficient 1970s technology and were replaced with a modern unit using BACT. Nutrien continues to operate the No. 7 unit with world class environmental standards to this day.

Lithium Americas Thacker Pass

Most recently, Lithium Americas announced a 2,250 t/d plant in Thacker Pass in Nevada. This first unit is phase one of four planned for the location as part of a $2.23 billion loan from the US Department of Energy.

Each phase will use 2,250 t/d of sulphuric acid for leaching operations to produce 40,000 t/a of Li2CO3. The high-profile project has attracted numerous challenges from local objectors including cattle ranchers, indigenous tribes, and environmental groups resulting in immense pressure on regulators. Tail gas scrubbing and DCDA were just some of the many elements that contributed to satisfying air quality requirements and ultimately, presidential power under Donald Trump was required to authorise the permit in a timely manner. Unlike the Nutrien or Freeport sites which had existing industrial operations, greenfield sites like Thacker Pass must often meet even more stringent requirements to operate.

Regulations drive sulphuric acid plant technology

The common thread is that each project had to push emissions as low as feasible at the time of construction. Freeport’s peroxide scrubber; Aurora’s caesium-promoted catalyst; and Thacker Pass’s scrubber, were responses to the same underlying pressure – meet or exceed BACT requirements. History has shown that US federal and US state regulators will continue to pass more stringent regulations to further reduce emissions as a result of public pressure.

The next solution: ultra-low emission

Recalibrate is offering a next generation sulphuric acid plant with zero NOx and part per billion (ppb) SO2 and emissions. This is achieved by integrating an air separation unit (ASU) with a patented acid plant of reduced footprint but equivalent acid output. The Recalibrate technology uses pure oxygen from the ASU instead of air. Where enhanced oxygen combustion is a known strategy for lowering emissions, the technology has not been widely adopted due to the cost of generating elemental oxygen (O2). Through direct integration of the air separation unit (ASU) with the sulphuric acid plant, both processes have been concurrently optimised lowering ASU costs while maximising acid output, steam, and power generation from the acid plant. In a standalone ASU, energy is converted into cryogenic capacity used to separate purified streams of nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2), and argon (Ar) by distillation. Both product purity and composition can be tuned for a trade-off in capital costs and power consumption – the main cost driver for oxygen from the ASU. Furthermore, heat and steam losses have been reduced by integrating the operations together, instead of operating as separate processes.

Recalibrate technology versus a traditional DCDA design

Producers can expect comparable outputs to a traditional DCDA process with heat recovery, and the ratio of outputs can be varied depending on user preferences or geographical requirements. Operators conditioned for today’s state-of-the-art DCDA process will find the Recalibrate process easy to adapt and can expect competitive steam, power, and acid outputs. Investors will find an increase in speed to market for new plants due to lower environmental barriers.

Equipment comparison

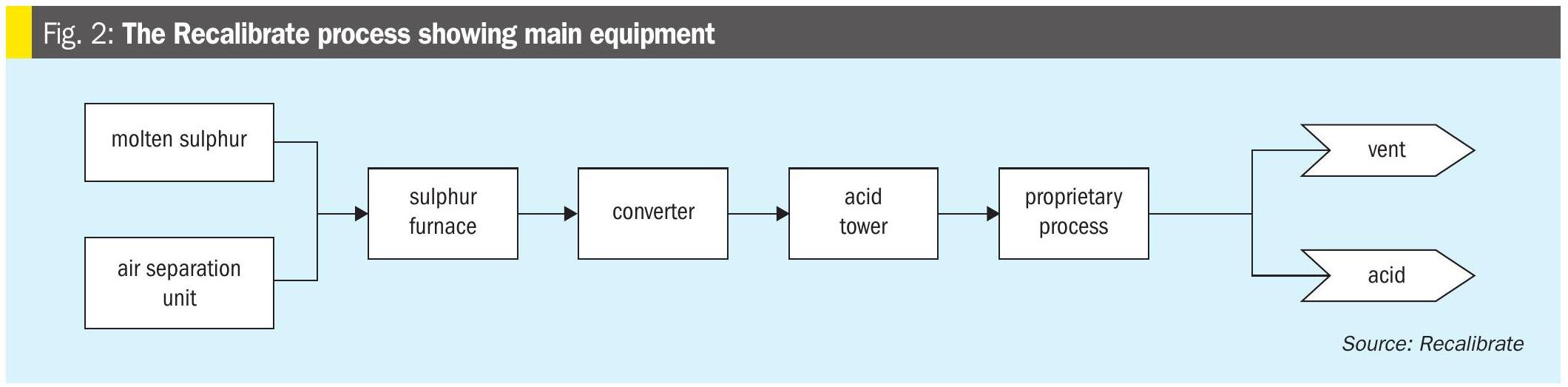

Equipment for the acid process remains similar in function to traditional plants (Fig. 2). Operators can still expect a process that feels familiar although the plant layout and unit operations have been modified for an improved design.

Improved operations: Single pass converter and lower catalyst costs

Recalibrate’s next generation converter has been engineered to provide better kinetics for SO2 conversion and improve heat transfer efficiency. The new converter can be expected to cost half that of traditional plants. In conjunction with a proprietary catalyst, an operation can save ~$15 million over 50 years in catalyst for a 1,000 t/d plant.

Low emissions for better operations and public relations

Any experienced acid plant owner will say that the appearance of the stack is one of the key factors in maintaining good public relations, and there are numerous operational issues contributing to poor stack visibility. The most common problems are stack spitting and acid mist formation. Stack spitting occurs when solid sulphate deposits are formed on carbon steel and then dislodged by fast flowing gas. This is often recognised by the surrounding community when discoloration is noticed on buildings and vehicles. That damage must then be repaired by the plant operator at both a financial and political loss. Acid mist formation is the phenomenon whereby a visible cloud of acid vapour is emitted and usually results from high moisture contents in stack gases. Moisture can be introduced from several upstream operations in the dry section of the plant including:

- mist eliminator damage or gasket leaks;

- poor performance in the drying tower;

- acid mist formation from hot gas entering the absorber tower;

- poor performance of the absorber tower due to an out of balance acid concentration;

- mechanical failure of tower packing;

- steam leaks from economisers, coolers, and other acid / water contact points in the process.

These issues are often difficult to identify and even more difficult to correct. Some problems may require a prolonged reduction in rates or sustained downtime to perform repairs. Like stack spitting, acid vapour results in negative externalities for the surrounding community and will come at an immense cost to plant owners. Recalibrate’s technology eliminates the risk of visible stack emissions as the process emits strictly oxygen, nitrogen, and trace argon. There is little risk for SO2 and acid mist, and no risk of stack spitting or NOx emissions as these are eliminated elsewhere in the process. Even a small traditional DCDA technology plant has a stack with a diameter several feet wide. Recalibrate’s technology is much smaller, roughly four inches in diameter for the same capacity plant. Recalibrate’s stack visibility is greatly reduced, reducing concerns from the public. Several other key pieces of process equipment have also been engineered with the goal of reducing the visible operating footprint for surrounding communities. Recalibrate’s technology enables companies to be persuasive to regulators on technical merits where projects are proposed that beat the strictest emissions rules in the country. Early adopters of this technology will likely find that regulators become allies rather than adversaries. This means faster permitting times, reduced project risk, and faster speed to market.

Steam output comparison

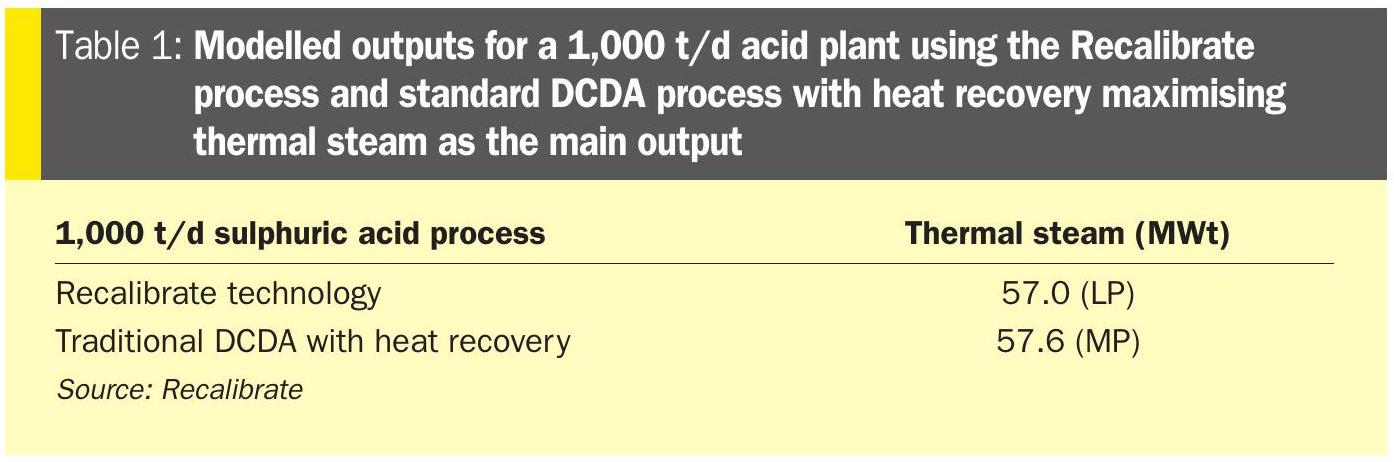

Steam and power are both important co-products of sulphuric acid production. The process is highly exothermic, so capture and use of that energy as steam or power is critical to the economics of a plant. Two, simplified, base case scenarios are presented comparing the Recalibrate technology against the traditional DCDA design using a 1,000 t/d acid plant basis where either power or steam is the desired coproduct. Steam and power are compared by first addressing the power generation for each case and comparing them. The net power is calculated as the “net power export”. The steam only case assumes the only power generated is what is needed to supply both the ASU and acid process (Table 1), resulting in net power export of zero (consumption equals production). The rest of the steam is exported at lower pressure, which can be used as process heat on site.

Here the steam output from the standard technology is nearly identical to the Recalibrate technology, but a cost for higher conversion efficiency is paid in steam pressure. Operators in regions with lower energy costs or with high value use for thermal steam will find the Recalibrate process flexible to fit their needs.

Power output comparison

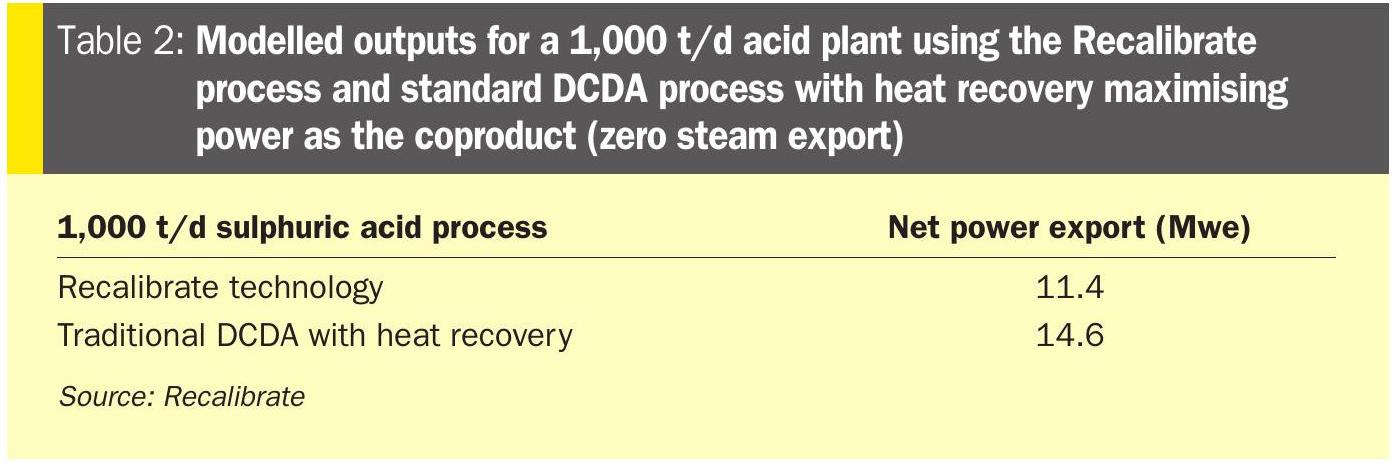

Table 2 also uses the net power export to compare the technologies for the power only case: all high-pressure steam from the acid plant is converted into electrical power using a steam turbine.

The net power export shows a net power penalty of 3.2 MWe for the Recalibrate process from operating the ASU and resulting higher conversion rate. However, consideration should be given to the scenario where oxygen is already available onsite or where a traditional plant is undesirable due to emissions regulations. The cost of operating the ASU can be offset if oxygen is needed for other onsite processes. Another consideration to remember is speed to market. Speed to market is a significant concern as obtaining mining permits can take eight to nine years on average, and often longer for complete operations. As stated earlier, these delays can cause project returns (IRR) to drop by up to 50% before production begins, eroding project value (NPV) by up to 70% compared to initial forecasts. The Rosemont Copper Mine in AZ lost an estimated $3 billion in value after eight years of permitting delays. The benefits from faster permitting processes offset the impact of reduced power production.

Conclusion

Recalibrate has developed a next generation sulphur burning plant to produce sulphuric acid with ultralow SO2 and zero NOx emissions. The main features of the technology are:

- smaller and simpler acid plant with a single adsorption tower;

- no NOx emissions from the pure oxygen;

- higher SOx conversion from the pure oxygen and proprietary process and catalyst, leading to almost no SOx emissions;

- small stack (4-inch diameter compared to 4 ft diameter for a 500 t/d sulphur burner);

- no acid mist concerns due to small SOx emissions;

- lower failure risks due to low amount of SOx gas in the system;

- thermal efficiency from integration with an ASU or other form of pure oxygen compared to other enhanced oxygen methods;

- the design scales linearly, no big jumps in capital cost for larger scale systems;

- flexibility to design the plant to tailor the steam or power output to customer requirements;

- potential additional byproduct sales (nitrogen, argon, oxygen) with an integrated ASU.

Recalibrate is actively looking for partners for a demonstration plant, plant number one. The plant is currently configured only for sulphur burning. However, there is a product development pipeline that expands the sulphur feeds to H2S, sulphuric acid recovery, metallurgical off gas, and industrial SOx.

Recalibrate’s development pipeline also includes the ability to produce ultrapure acid and add core elements of the technology to retrofit existing plants to reduce SOx emissions and enhance conversion rates instead of adding a scrubber. The company is also looking for operators in these areas interested in supporting these product development efforts.

This article is based on the white paper “Recalibrate™ – to zero emission sulfuric acid production” by Ben Egelske, Rick Davis, Ron Cloud, Tony Miles, Gerry d’Aquin, Billy Barron, Kris Van Damme, Bob Gulotty, Lee Mitchell.