Sulphur 422 Jan-Feb 2026

28 January 2026

Catalyst unlocks new performance opportunities

SULPHURIC ACID CATALYST

Catalyst unlocks new performance opportunities

In this real world case study, Martin Ariel Alvarez and Mårten Nils Rickard Granroth of Topsoe A/S demonstrate how cost effective catalyst changes can result in significant production increase without any equipment changes or revamps, all while maintaining compliance with emission limits.

Legislation on SO2 emissions and shifting market dynamics have long been key drivers of innovation in the sulphuric acid industry. For acid producers, the challenge of increasing throughput without compromising emission levels remains a top priority. However, stricter SO2 limits and the high costs of major revamps with lengthy payback periods make this goal increasingly difficult to achieve.

Traditional methods of boosting production eventually reach their limit. Further increase of gas flow is often not feasible due to blower constraints, and no more caesium catalyst can be added to avoid that stronger feed gas causing high emission. So, what options remain for plants that have already implemented all the usual upgrades but still need to push production further?

To address these challenges, Topsoe introduced the VK38+ catalyst in 2020 – a highly potassium-promoted solution designed to tip the scales and meet modern operational demands. Five years later, VK38+ has demonstrated its superior performance, with over a dozen successful references worldwide, some already entering their second campaigns with this catalyst.

This article shows a real-world case study from a sulphur burner unit associated with a large-scale fertilizer complex. The operator had through hard and diligent work succeeded in improving most performance metrics, but being ambitious, they wanted to increase productivity further. As is the case for many debottlenecked plants, the blower was already running at maximum capacity, and the pressure drop across the plant prohibited further flow increases. By working with Topsoe and implementing a solution including VK38+, the plant achieved a significant production increase without any equipment changes or revamps, all while maintaining compliance with emission limits. Best of all, the investment in the catalyst is estimated to be paid back in less than one campaign.

The sulphuric acid plants

In the production of any commodity, operational excellence is key to turning a profit. Sulphuric acid is no exception and across the globe producers are continually seeking to boost production capacity, implement better operational practices and comply with increasingly stringent SO2 emission legislation. This case study reports on the successful implementation of a new Topsoe catalyst to boost acid production at a large-scale fertilizer complex.

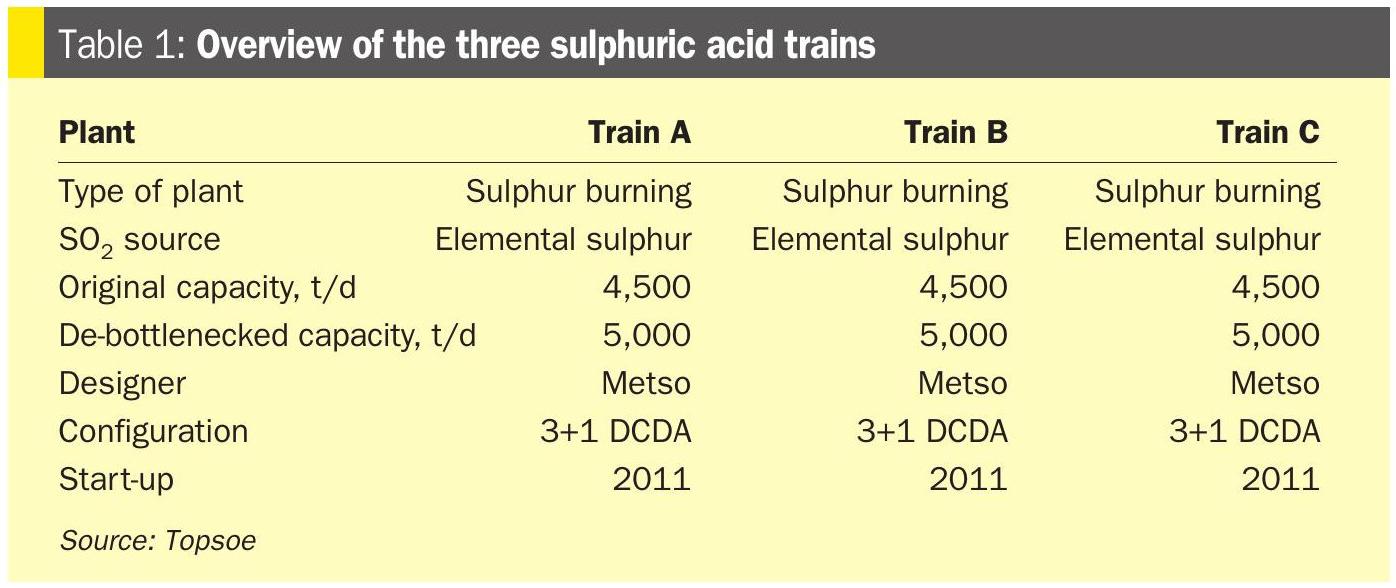

Since its start-up in 2011, the complex – comprising of three world scale production trains (A, B, and C), each originally designed for 4,500 t/d of sulphuric acid – has consistently pushed the boundaries of performance, striving for record-breaking throughput while maintaining a strong focus on sustainability and emission compliance.

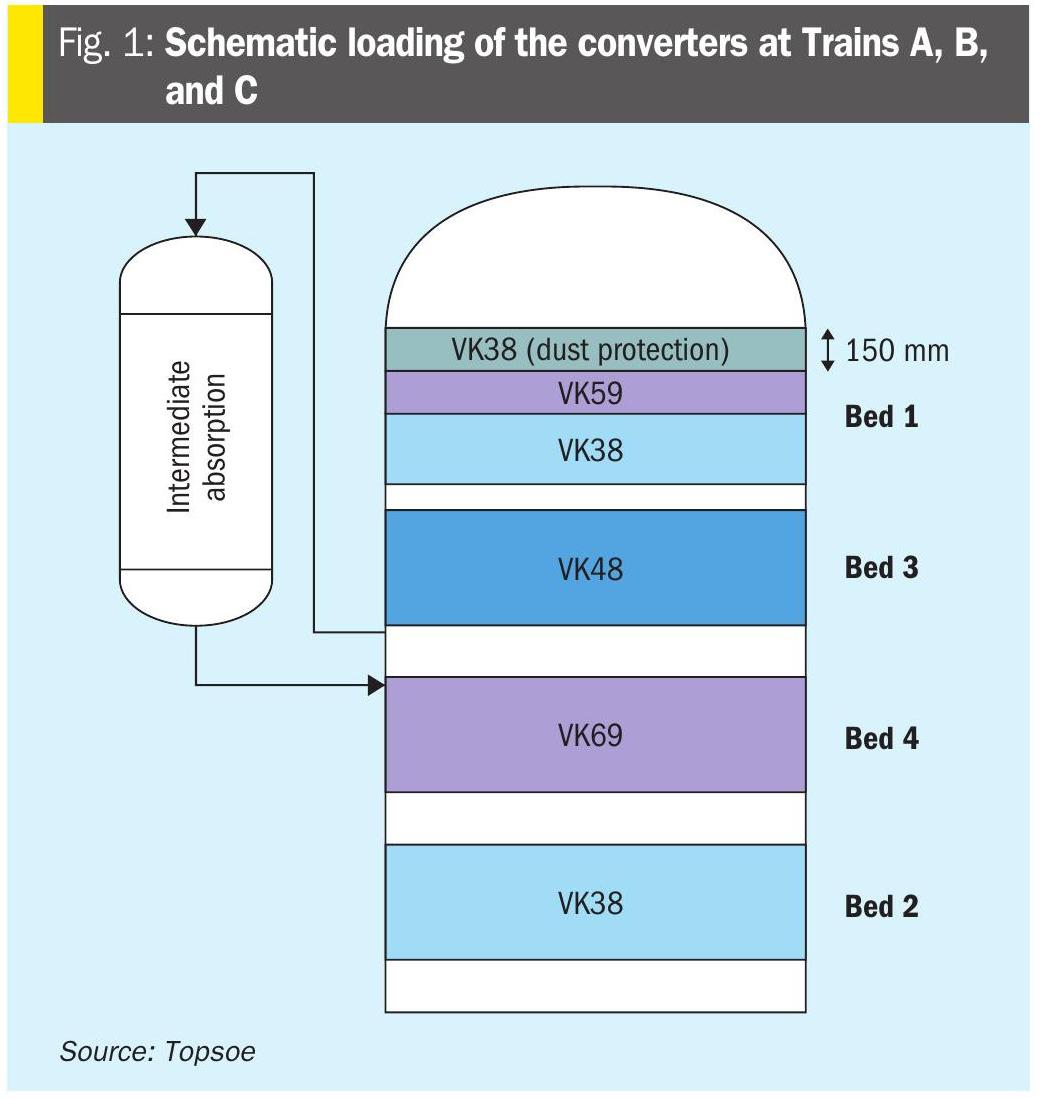

From the very beginning, the fertilizer company relied on Topsoe sulphuric acid catalysts in all three trains and has worked closely with Topsoe to continuously optimise and maximise production in a partnership of over 15 years. The initial catalyst loadings for the trains were specifically designed to achieve maximum capacity, incorporating not only standard products like VK38 and VK48, but also specialty solutions such as VK38 25 mm for dust protection, as well as VK59 and VK69 (see Fig. 1). These advanced catalysts help mitigate factors that could otherwise limit production, such as pressure drop accumulation in bed 1 or increased emission levels.

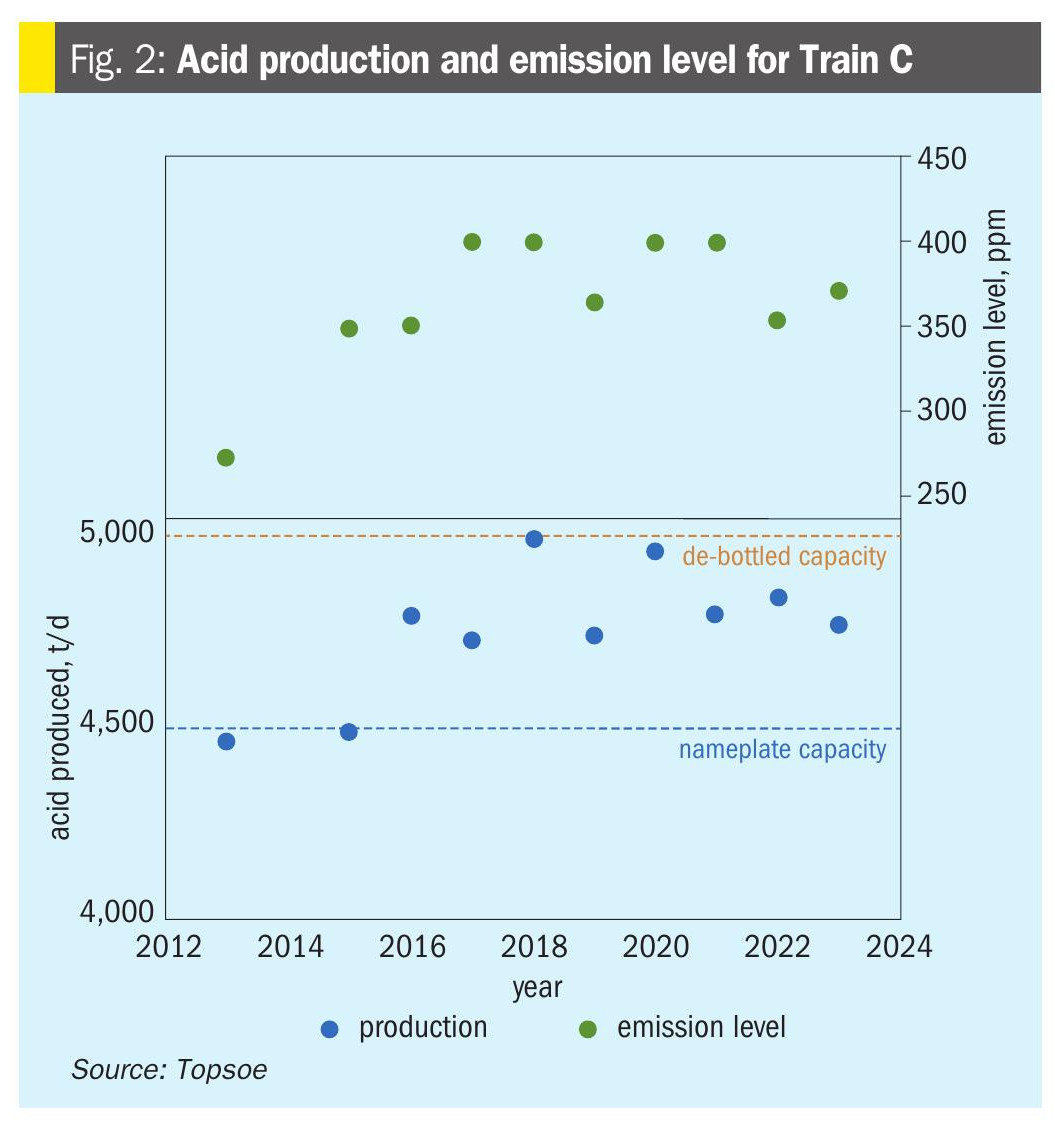

Over these many years, the plant has operated at the limit of emission levels and has been able to achieve production capacities above its nameplate capacity (Fig. 2). All three trains have operated at approximately 4,700 to 5,000 t/d of acid for campaigns lasting 36 months.

Having a highly active catalyst available is an important enabler for ensuring maximum capacity; however, it is not the only one. Many other factors have also been addressed by the company to achieve this goal.

Boosting acid production even further in Train C

Even though for more than ten years the plant has been able to operate above nameplate capacity, when the new highly active catalyst, VK38+, was introduced the fertilizer company requested Topsoe to conduct a study on the feasibility of utilising the extra activity of this new catalyst to increase production even further.

Topsoe worked together with the company to evaluate different alternatives and analysed the various bottlenecks that would need to be addressed in order to increase acid production for Train C, which was scheduled to be the next one to have its turnaround at that time.

The sulphuric acid trains are S-burning plants, which for a double absorption plant effectively means that production can only be increased by burning more sulphur:

- If more sulphur is burned and the airflow is increased simultaneously, production will increase and the SO2 concentration of the feed gas will remain at the same level.

- If more sulphur is burned but the airflow remains constant, production will increase, but the SO2 concentration of the feed gas will also increase (and the O2 level will decrease).

If the catalyst loading is not upgraded, SO2 emissions will increase in both cases. However, the pros and cons of each option are different. Which option is best, depends on the specific case and plant.

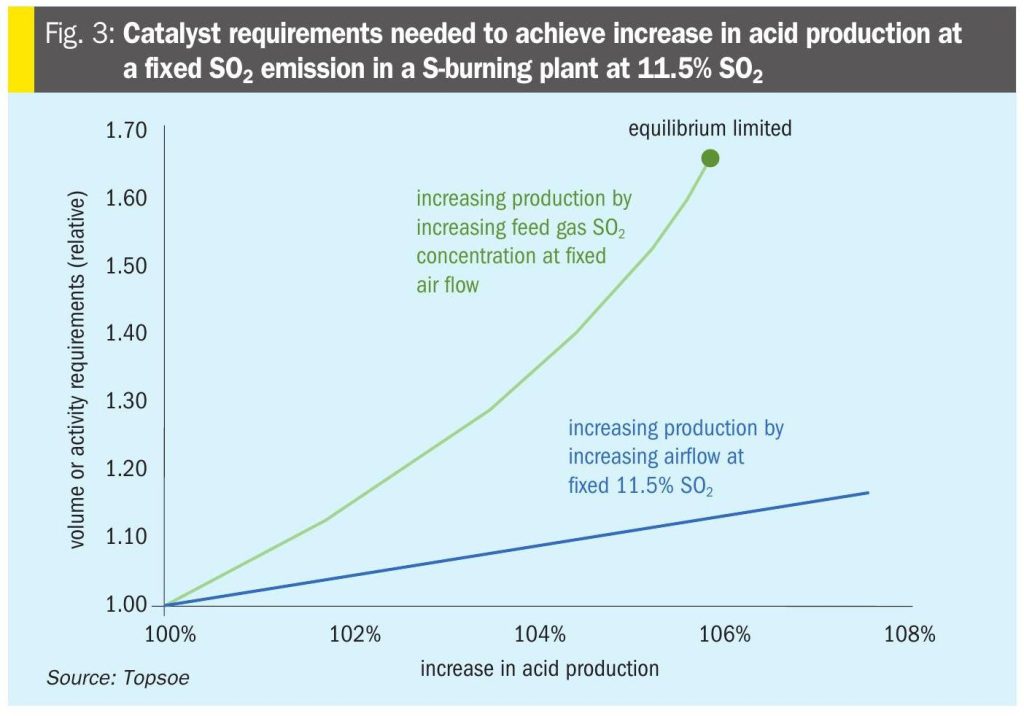

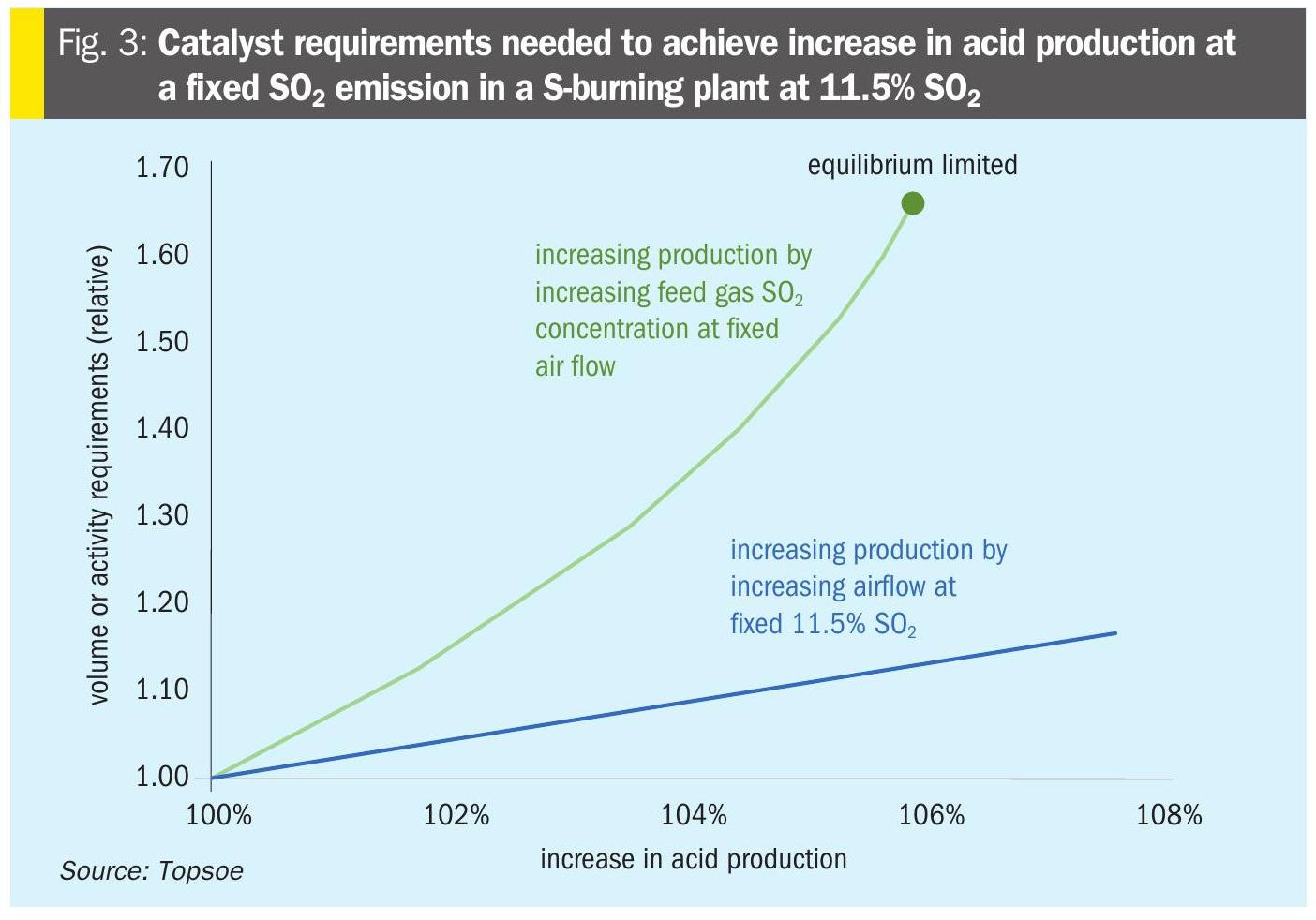

In general, for S-burning plants operating above 11.5% SO2, the first option (increasing production by increasing airflow) will require some catalyst upgrade (more catalyst volume or more active catalyst), but not as much as the second option (increasing production by increasing the feed gas SO2 concentration). However, increasing the flow results in a higher pressure drop across the unit, which may not be possible for the blowers to accommodate.

The second option (increasing production by raising the feed gas SO2 concentration) could, in principle, be attractive because it does not increase the pressure drop. S-burning plants do not experience the catalyst high-temperature limitation that some other types of plants have, as they operate with SO2 concentrations around 10–12%. However, this does not mean the SO2 concentration can be increased indefinitely, as there may be other equipment limitations (e.g., the furnace) that cannot operate at much higher SO2 concentrations and temperatures than originally designed.

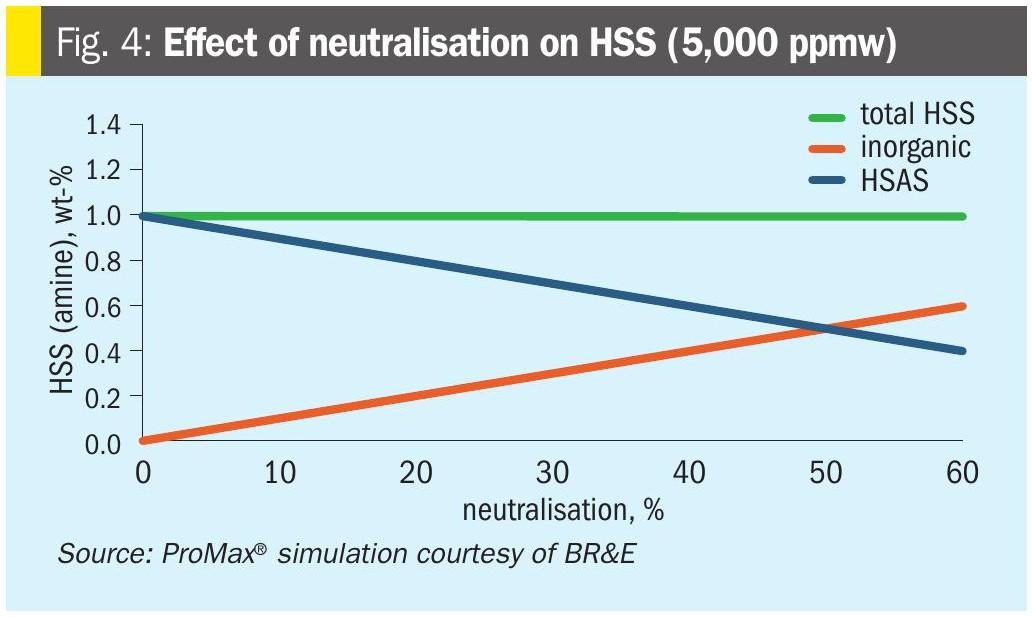

Fig. 3 showcases in the X-axis the increase in production for a plant operating originally at 11.5% and a maximum emission level that cannot be exceeded.

If the increase in production is made by increasing the airflow (blue line) and keeping the feed gas at 11.5% SO2, the catalyst volume/catalyst activity requirement increases linearly.

However, If the increase in production is made by increasing the SO2 concentration and keeping the airflow constant in its original value (green line), the increase in catalyst volume / catalyst activity turns quickly exponential. For S-burning plants, very high SO2 concentrations could not be thermodynamically possible, due to the equilibrium not permitting high enough conversion in the temperature where the catalyst is active.

In many cases, one would utilise a high activity caesium catalyst in the last bed to counteract the less favourable gas composition. In this particular case, this solution had, however, already been employed during the original design of the plant to allow it to achieve the high name plate capacity with a somewhat smaller plant than otherwise would have been possible. Furthermore, the company had already taken advantage of the highly active caesium catalyst VK69 in bed 4 when pushing the production well over name plate capacity, resulting in plants operating close to the emission limit.

The plant in this case was therefore a case of a unit operating at the maximum capacity permitted by emissions, with the last bed fully loaded with caesium-promoted catalyst. Traditional approaches would have indicated that the limit had been reached. However, with the new highly active catalyst VK38+, there was an opportunity to boost the production further.

The Topsoe team used their proprietary simulation models and found that there was still room to further increase acid production by combining an increase in SO2 concentration to around 11.9% to 12.0% (from 11.7 to 11.8%) with an increase in airflow to approximately 400,000 to 410,000 Nm³/h (from 370,000 to 385,000 Nm³/h). These new conditions would result in an acid production increase of around 6%, without raising emission levels if the catalyst loading was upgraded. The additional activity required for the new conditions of higher SO2 and higher flow would be provided by using VK38+ in bed 1 and a top-up with fresh catalyst for bed 2 (20% make-up VK38), bed 3 (10% makeup VK48) and bed 4 (10% make-up VK69).

When this option was presented to the fertilizer company, they confirmed that there was some room to increase the SO2 concentration to 11.9% to 12.0% (from 11.7 to 11.8%), but not beyond that due to plant and equipment constraints. On the other hand, the blower had adequate capacity for the new airflow, but there was a concern that under the new, higher flow conditions, the pressure drop across bed 1 could limit capacity for the latter half of the campaigns.

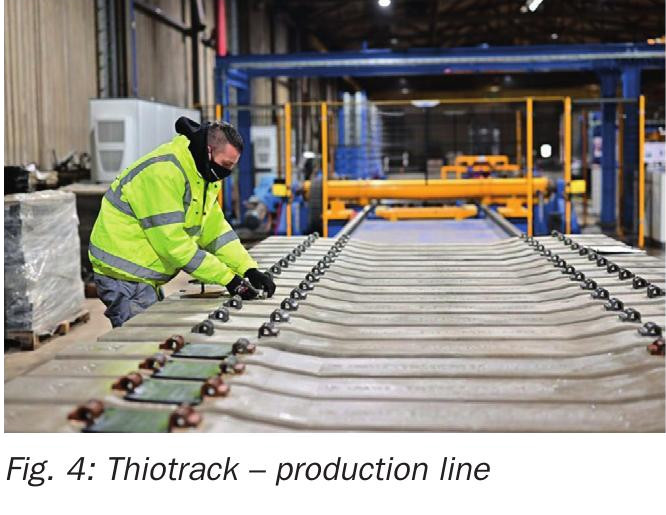

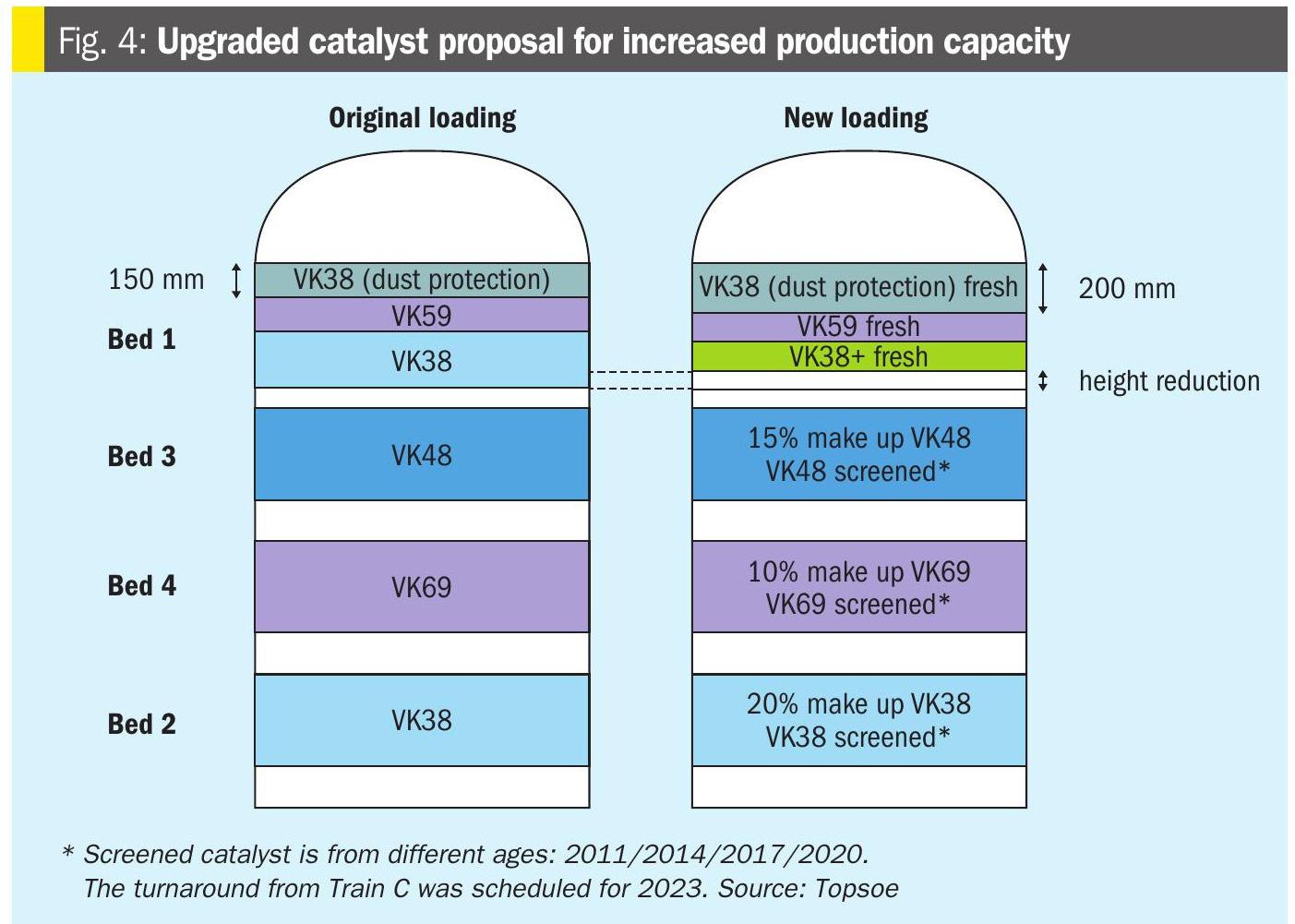

To address this concern, Topsoe showed that since VK38+ has higher activity than VK38, the bed 1 could be short loaded even for the new, more demanding, conditions, thereby reducing the pressure drop over bed 1. Additionally, although 150 mm of dust protection catalyst in the first pass has worked very well previously in these plants, it was proposed to capitalise on the extra available height and increase the dust protection layer to 200 mm to increase dust capacity further. The 150 mm layer used to this point had allowed the trains to achieve three-year campaigns on multiple occasions, however with the larger dust capacity the intention was to be able to increase this further. Extra dust capacity could also come in handy should the capacity boost lead to an increased dust load. The final proposal for increasing production is shown in Fig. 4.

Business case

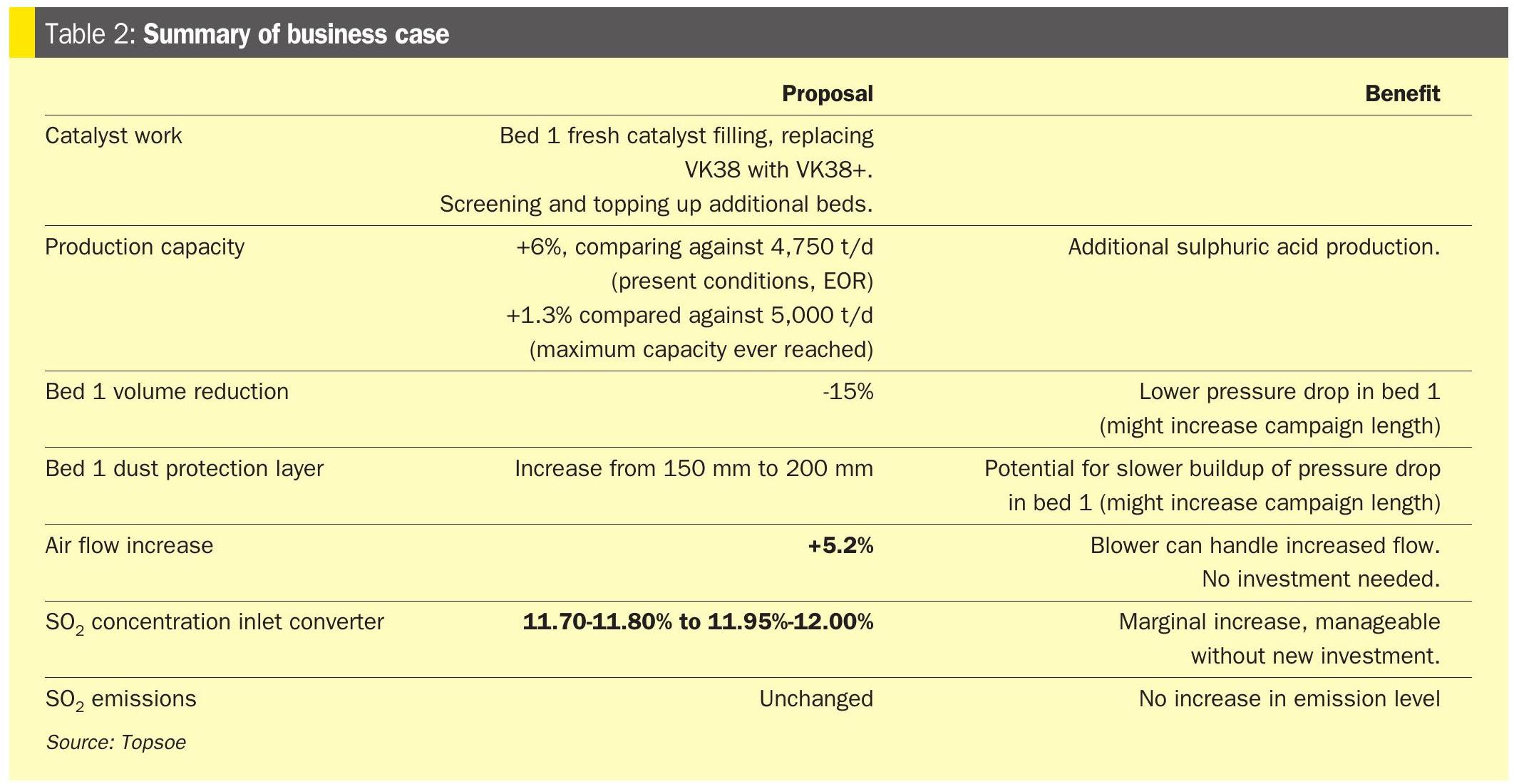

The fertilizer company prepared a business case to evaluate the benefits and payback period of the new catalyst upgrade. In other words, they calculated how long it would take to recover the cost of the new catalyst through the additional earnings from increased acid production (see Table 2).

A very conservative return on investment, considering an increase of +64 t/d per day (compared to the maximum capacity ever reached for Train C, 5,000 t/d), was calculated by the company. They determined a payback period of 1.5 years.

This return on investment is conservative, as it does not account for savings from reduced pressure drop or extended campaign durations. Furthermore, it compares the new, higher production level to the previous maximum output. In reality, when compared to the plant’s current operating level, the increase would be more than 300 t/d, not just 64 t/d. In any case, even under those conservative assumptions, the payback period was very attractive (the investment would be recovered in half a campaign).

The proposal was approved by the fertilizer company, and the catalyst loading was upgraded.

Results from real operation of Train C WITH VK38+

The fertilizer company started up Train C with the new loading at the beginning of 2024 and shared the production results.

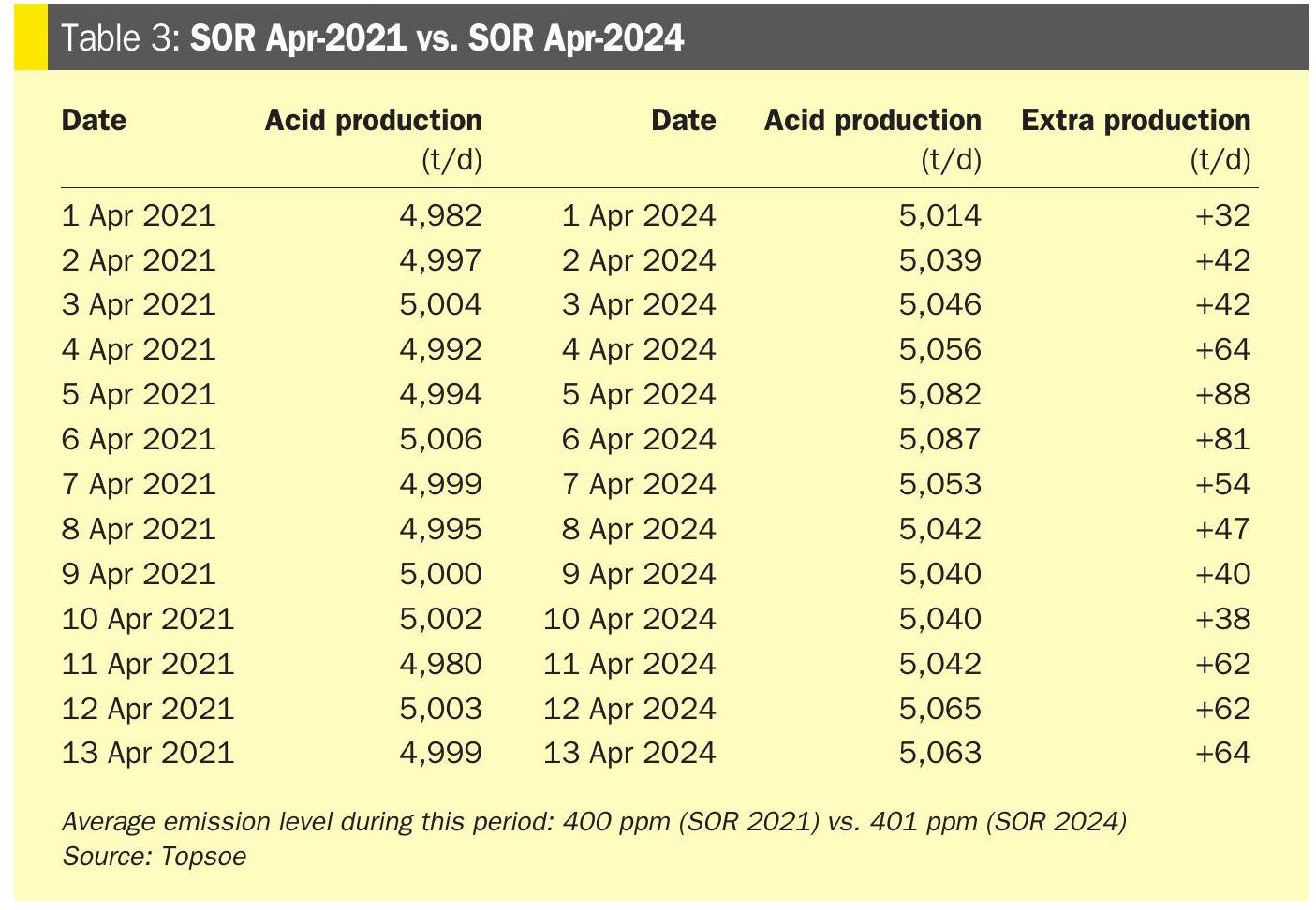

The new production with the upgraded loading at start-of-run (SOR) in April 2024 is compared against the value at the same time during the last turnaround (last SOR, April 2021) in Table 3.

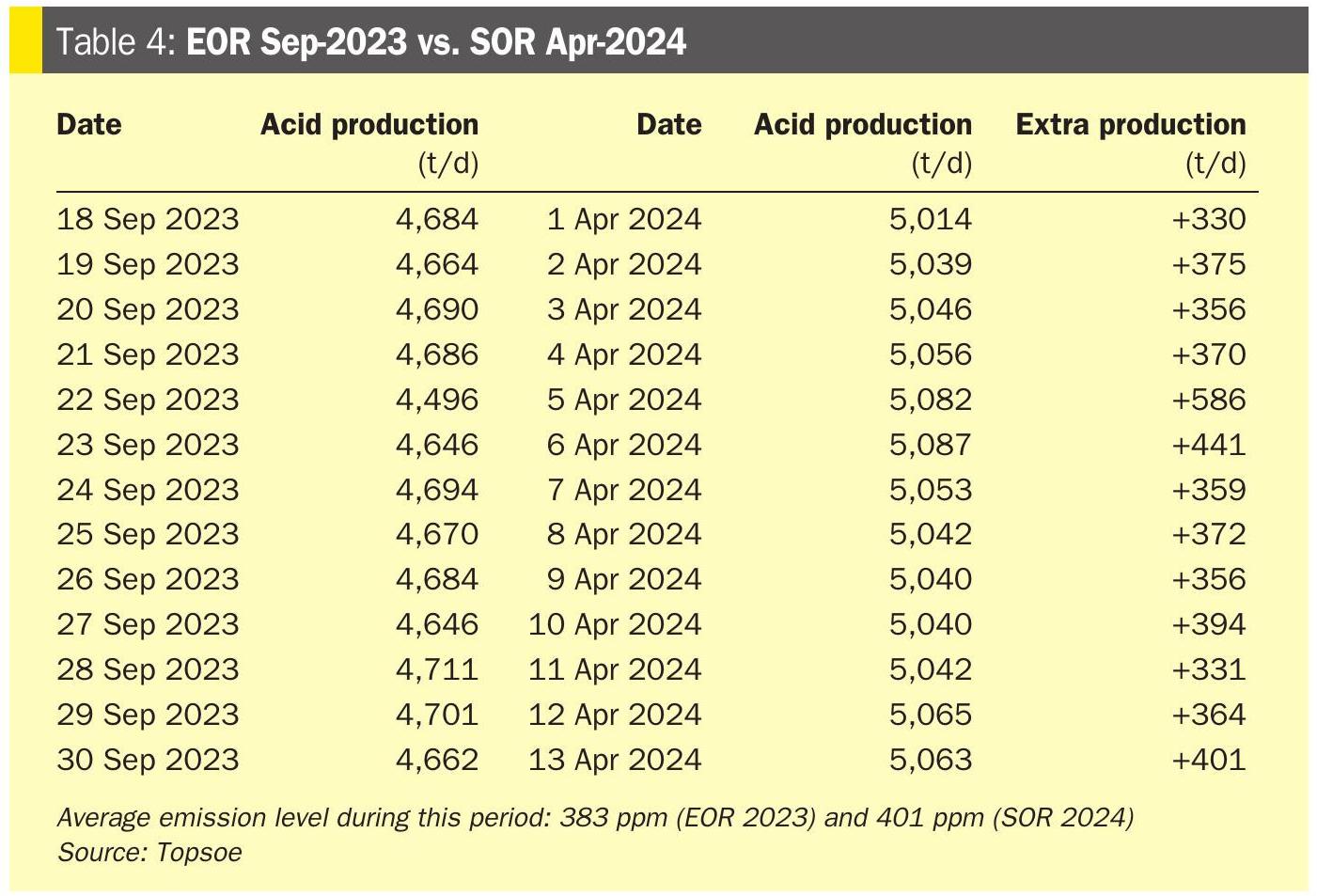

The new production with the upgraded loading at SOR (Apr 2024) is also compared against the production before the turnaround (September 2023) in Table 4:

As can be seen above, the upgraded VK38+ loading has significantly increased production after the turnaround (average: +387 t/d).

The improvement is also evident when compared to the maximum capacity period at SOR in April 2021 (average: +55 t/d).

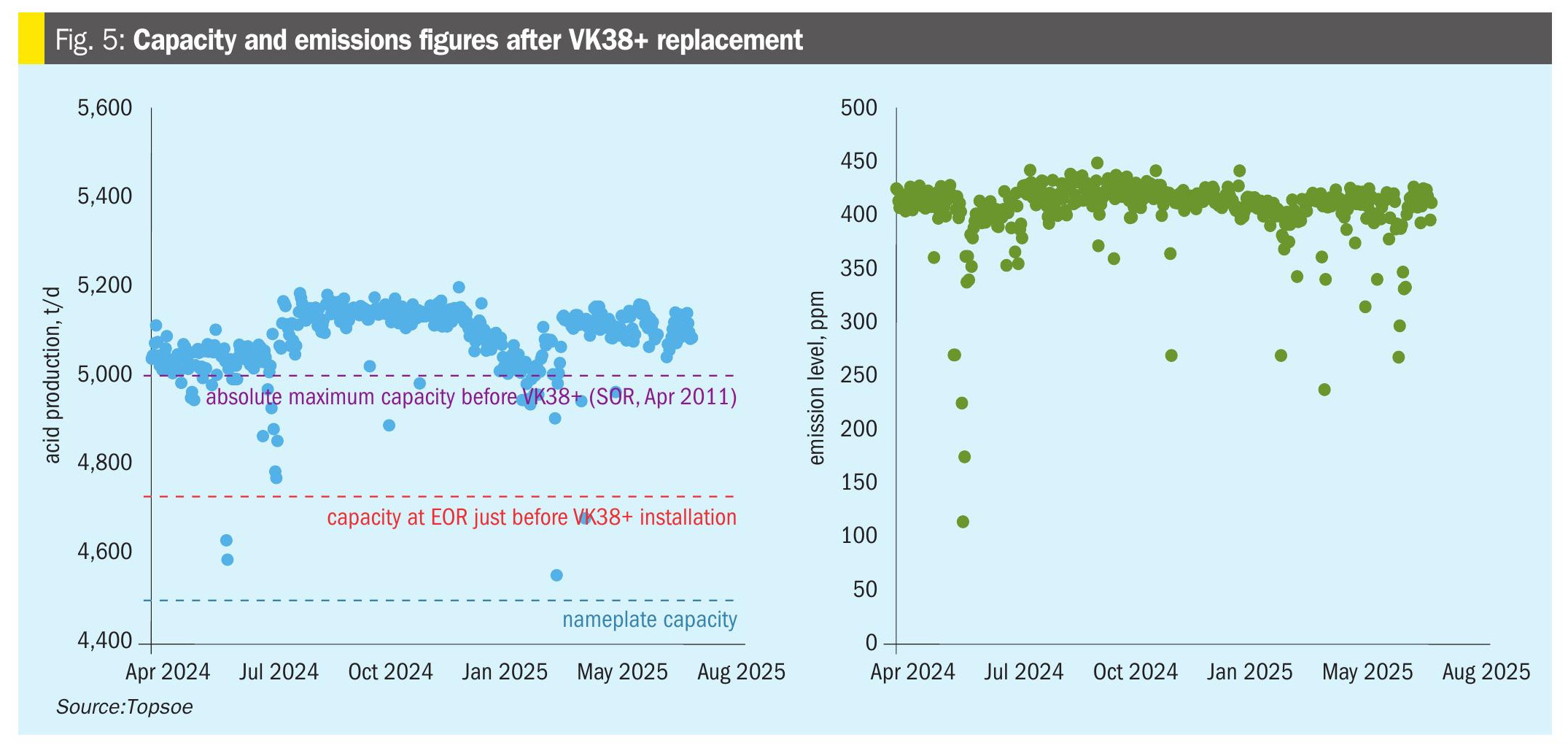

This increased acid production has been sustained to the present day. Fig. 5 shows how the new capacity has consistently remained above the previous maximum throughout the campaign, while emission levels have remained practically unchanged around 400 ppm, in compliance with the environmental legislation.

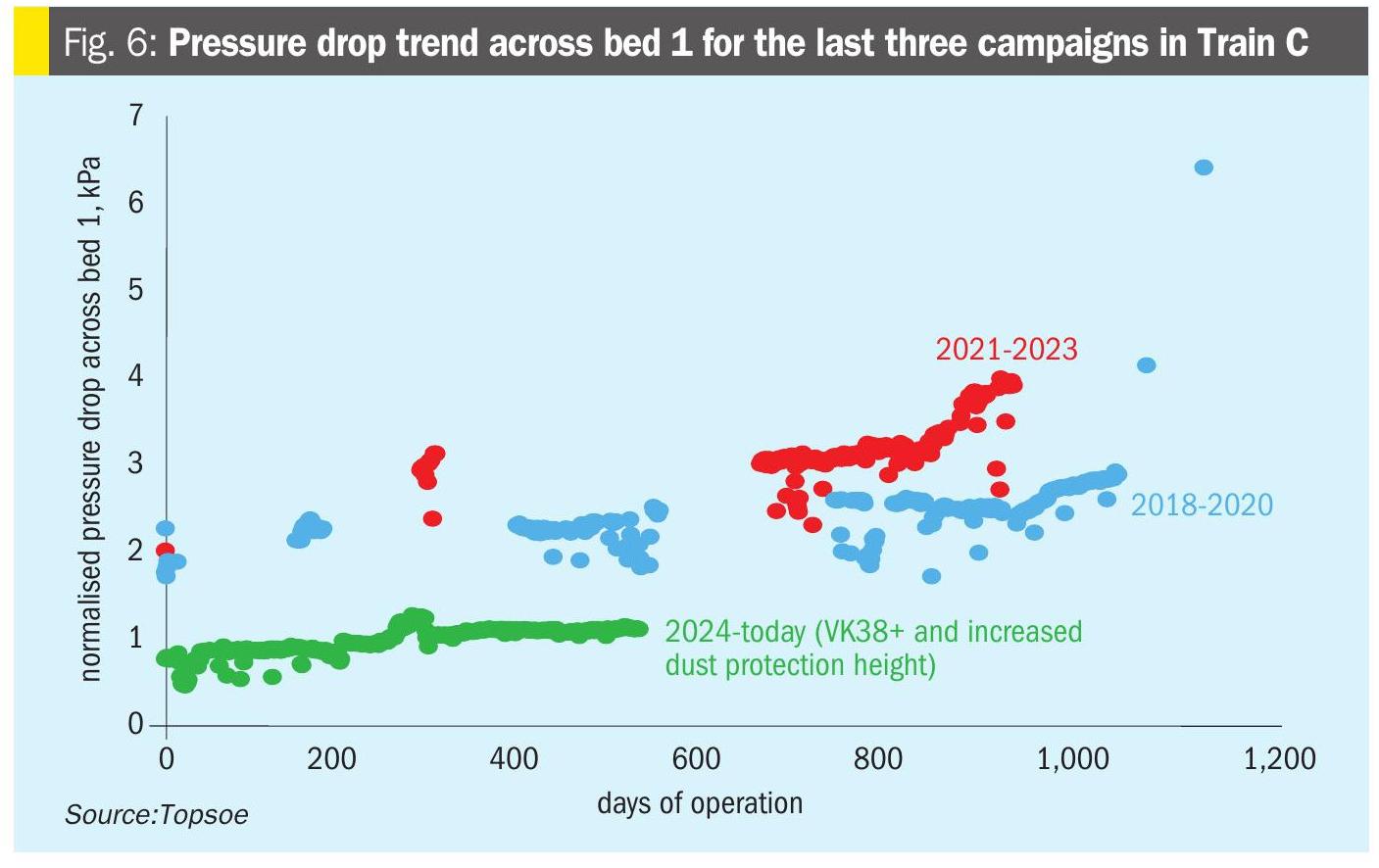

The pressure drop for the current campaign across the first pass with the new loading featuring a higher dust protection layer and a short-loaded VK38+ bed compared to the last two campaigns is shown in Fig. 6 (the values have been normalised using the design flow for comparison purposes):

After the full bed catalyst replacement and short-loading with VK38+, the pressure drop across bed 1 is considerably lower than the original values (1 kPa vs 1.9 kPa at SOR).

As a result, the operational team at the fertilizer company expect to be able to run Train C for approximately 3.5 to 4 years, taking advantage of the lower pressure drop.

Conclusions and future plans

The catalyst upgrade using VK38+ has proven to be a significant success the fertilizer company, enabling higher production rates and lower pressure drops in a plant that was already operating at its maximum capacity. These improvements were achieved without the need for important modifications in the plant – only by changing the catalyst type.

This case demonstrates how VK38+ can unlock new performance opportunities, even for S-burning plants operating with high SO2 strength and with full converters and Cs catalyst beds, where conventional approaches would suggest that further increase are not possible without major revamps.

The success of this project was rooted in strong collaboration and partnership between Topsoe and the fertilizer company. Open communication, thorough information sharing was essential to realising these benefits. The company’s proactive approach to plant improvement and their commitment to achieving the best possible performance were also key factors.

The payback period for the catalyst upgrade was fast, further validating the business case for VK38+. Following this success, the same strategy has been applied to Trains A and B, achieving similarly positive results.