Sulphur 421 Nov-Dec 2025

21 November 2025

Sulphur and sulphuric acid in southern Africa

SOUTH AFRICA

Sulphur and sulphuric acid in southern Africa

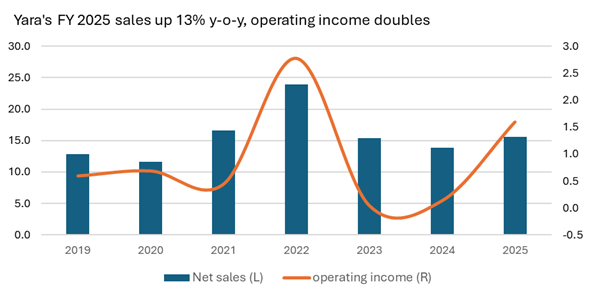

While north Africa’s sulphur demand is dominated by its phosphate industry, south of the Sahara it is copper, cobalt and uranium mining, leaching and smelting that hold sway over acid production and demand.

Sulphur

There is very little domestic sulphur production in the region, and what there is comes from a relatively small refinery sector. Refining capacity in subSaharan Africa is also uneven: there are a few larger, highercomplexity installations, and several small or lowercomplexity refineries, where capacity and reliability are often constrained by ageing equipment, feedstock logistics, and underinvestment. Many countries import refined products despite having refineries because of outages or limited runs. The region produces around 5.5% of the world’s oil, but has only 1.5% of its refining capacity.

Significant sulphur production only comes from South Africa and Nigeria. South Africa had six refineries at the start of 2020, four of which processed imported crude. However, during 2020-22 three of the six closed down – Sapref and Engen in Durban and the PetroSA gas to liquids plant at Mossel Bay, while a fourth – Astron in Cape Town – was shut for a considerable period after an explosion. The outcome is that South Africa has become a massive importer of refined petroleum. The US Energy Information Administration estimates that South Africa produces only 20% of its domestic fuel requirements and is forced to import the rest. The problem was the cost of installing new treatment sections at the country’s ageing facilities to be able to meet a proposed 10 ppm sulphur fuel content. The country’s Central Energy Fund has bought the idled Sapref refinery, with 180,000 bbl/d of capacity, for a token sum, but a planned investment programme for it has failed to materialise. This leaves Astron, Natref at Sasolburg, and Sasol’s Secunda synthetic fuel complex as the last producers in the country. In 2024, South Africa produced around 350,000 tonnes of sulphur from these facilities.

In Nigeria, there are older refineries at Warri and Kaduna, but the largest and most modern refinery belongs to Dangote, and started up in 2023, with a capacity of 650,000 bbl/d. However, in spite of its size, the Dangote refinery produces only 30,000 t/a of sulphur at capacity, as Nigerian oil is relatively sweet and local fuel standards are fairly forgiving of sulphur content.

Mining and metals

Conversely, while the refining sector remains relatively stunted, the region’s metal mining operations continue to expand. Globally, copper supply comes mainly from Latin America (Chile, 23% and Peru, 10%), but Africa is second, with the DRC responsible for 14% of production, and Zambia at 4%. Copper production comes mainly from the central African Copper Belt, which stretches across the DRC and into Zambia. This belt is considered to be the largest mineralised sediment-hosted copper province in the world. There is also a secondary, less explored deposit in the Kalahari, across Botswana and into Namibia.

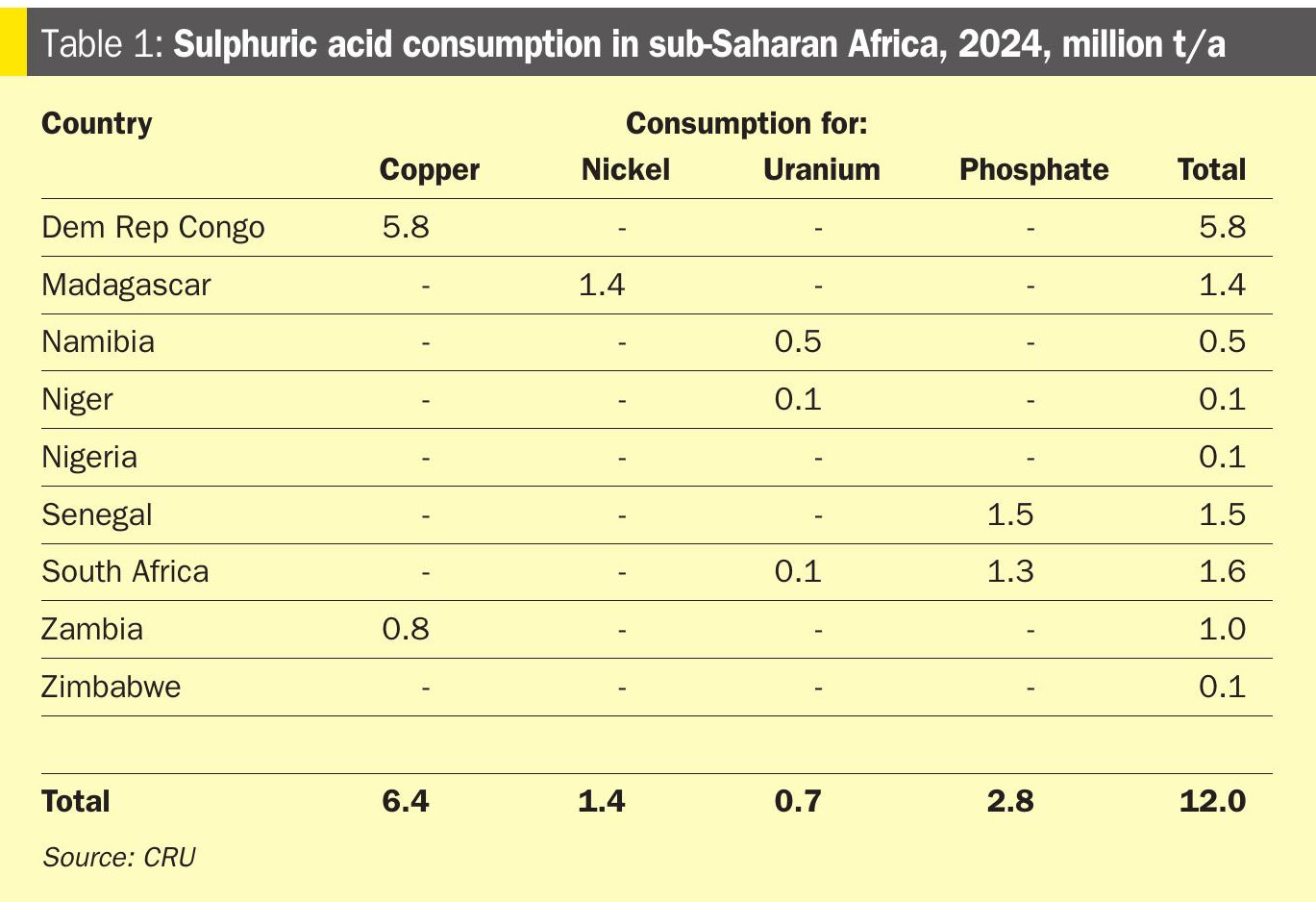

The copper belt also produces cobalt, increasingly important for battery production. Global cobalt production was 300,000 t/a in 2024, 80% of which came from the DRC. Other acid consuming industries include uranium and zinc mining as well as phosphates, and nickel leaching in Madagascar. While there is some industrial consumption, particularly in South Africa, as Table 1 shows, Copper, nickel, uranium and phosphate extraction together represent 95% of all sulphuric acid demand in the region, with consumption concentrated in just five countries: the DRC, Madagascar, Senegal, South Africa and Zambia.

DRC

Although the copper industry in the DRC is more recent than that in neighbouring Zambia, it has been the hot ticket for new copper discoveries and developments in recent years, much of it high-grade ores with copper content of 3-5%, as compared to a typical 0.6-0.8% elsewhere. Almost two thirds of new copper reserves identified worldwide were in the DRC’s Katanga Basin, according to S&P. The largest development has been at Kamoa-Kakula, run by Ivanhoe, which has expanded production to 600,000 t/a of finished copper, following the completion of a third concentrator last year. Kakula is estimated to be the world’s highest grade major copper mine, with an initial mining rate of 3.8 million t/a at an estimated average feed grade of more than 6.0% copper over the first five years of operations.

Other major operations in the country include Glencore’s Mutanda Mining (MUMI) and Kamoto Copper (KCC); CMOC’s Tenke Fungurume; ERG’s Comide and Frontier mines; China Molybdenum’s Tenke Fungurume Mine (TFM); and MMG’s Kinsevere mine. High copper grades have been amenable to leaching via solvent extraction/electrowinning (SX/EW), with consequent higher consumption of sulphuric acid. As Table 1 shows, the DRC’s copper industry consumed nearly 6 million tonnes of acid in 2024, almost half of the region’s total demand.

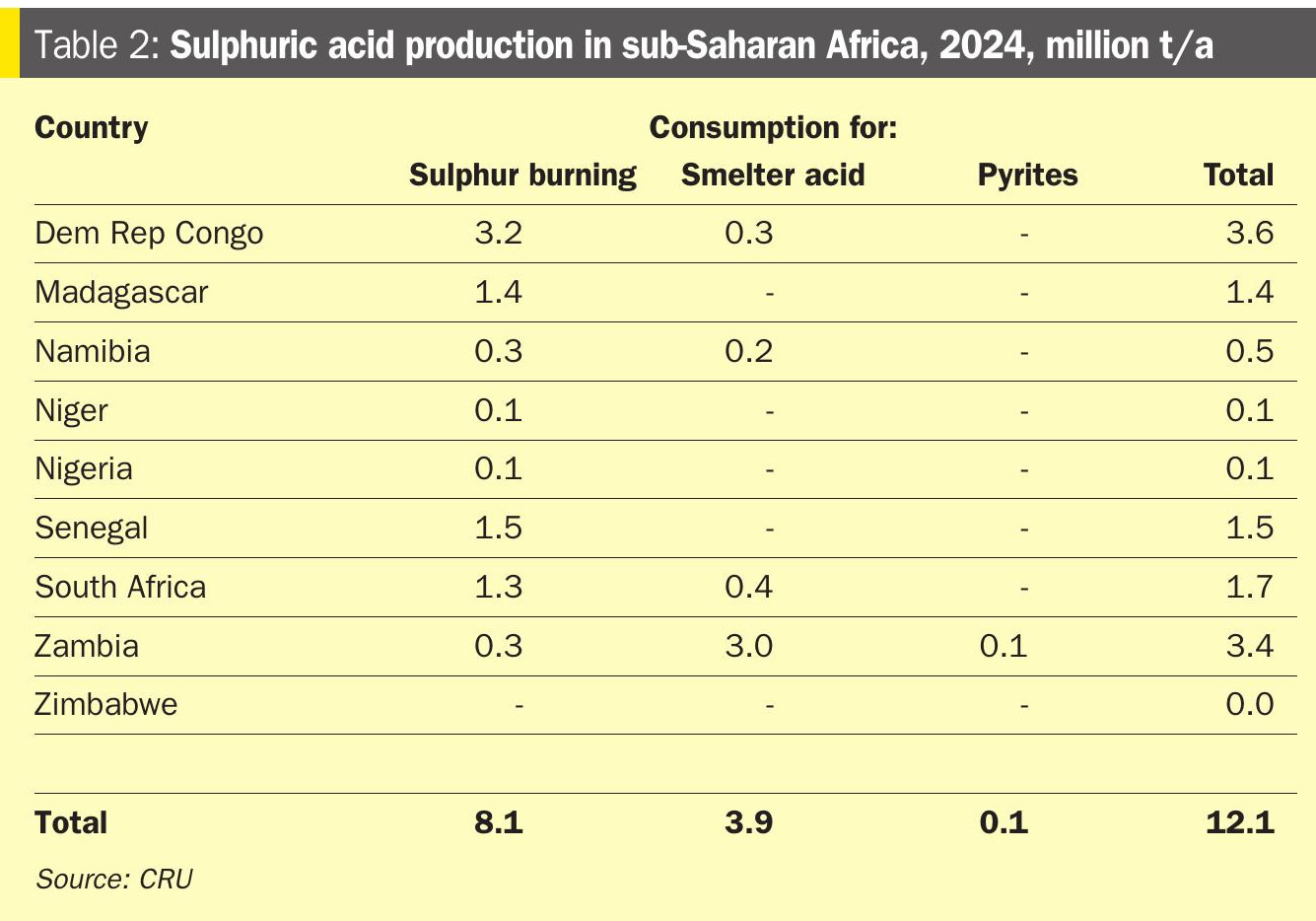

Acid to feed production initially came from smelters across the border in neighbouring Zambia. However, as Table 2 shows, there has been an increasing number of sulphur burning acid plants built in the DRC, and the need for domestic capacity in the DRC became more acute after disputes with Zambia over taxes on copper concentrates, which led to the loss of smelter acid production in Zambia. There are now sulphur-burning acid plants at Sicomines, Gecamines, and Tenke Fungurume. China’s Huyaou Dongfang has a 4,000 t/d plant, and Shalina Resources has 600 t/d of capacity in two plants.

Madagascar

Madagascar’s acid demand comes solely from the Ambatovy high pressure acid leach (HPAL) nickel facility, with a nameplate 60,000 t/a of nickel capacity, which started production in 2012. The plant has had operating issues, which saw Sheritt withdraw from the project, and it currently runs at around 50% of nameplate capacity, operated jointly by Sumitomo and Korea’s KOMIR. Sulphuric acid consumption is about 1.3 million t/a, requiring sulphur imports of 450,000 t/a to feed the sulphur-burning acid plant at the site.

Senegal

Senegal imports around 3-400,000 t/a of sulphur to generate acid for its phosphate production at Industries Chimique du Senegal, owned by Indorama since 2014. ICS is the largest producer of phosphate fertilizer in sub-Saharan Africa. Phosphate mining has been conducted since 1960, with phosphoric acid capacity added in the 1980s. The phosphoric acid plants are located in Darou and have a production capacity of 600,000 t/a. The downstream 250,000 t/a fertilizer plant is located in Mbao, which is close to the capital Dakar. ICS exports the majority of its phosphoric acid to India, while it sells its fertilizer products in West Africa and international markets.

South Africa

As well as being the only significant regional sulphur producer, South Africa also produces acid from the ageing Palabora copper smelter in Limpopo province, which produces around 60,000 t/a of copper and 180,000 t/a of acid. Anglo American’s Polokwane platinum smelter also generates 55,000 t/a of acid from a wet sulphuric acid (WSA) plant installed in 2018, and the Implats platinum smelter at Rustenburg has another 65,000 t/a of production. Sulphur-burning acid capacity is mainly dominated by phosphate fertilizer production. DAP and phosphoric acid producer Foskor buys in acid from local smelters as well as operating sulphur burning acid capacity in three large trains at Richards Bay. Sasol also produces sulphuric acid at its Secunda CTL plant.

Zambia

Zambia was once the largest copper producer in Africa, but has seen itself eclipsed in recent years by the DRC. Copper production actually fell to 700,000 t/a in 2023, the lowest level for 14 years. The government has ambitious plans to reverse this decline, and there are large new investments planned. Zambia has focused on copper smelting. Copper smelters operational in Zambia include Chambishi Copper at Chambishi, with 660,000 t/a of acid capacity, First Quantum Minerals at Kansanshi (1.0 million t/a), Glencore’s Mopani Copper at Kitwe and Mufulira, with a total of 760,000 t/a of capacity, ZCCM at Chambishi (90,000 t/a) and Vedanta’s subsidiary KCM at Nchanga and Nkana (total ca 1.0 million t/a of capacity). There are also sulphur burning acid plants at Solwezi (FQM)and Kitwe (Metorex), with a combined 300,000 t/a of capacity. All told, this brings Zambian acid capacity to 3.9 million t/a, far in excess of its approximately 1 million t/a of consumption. While excess acid is exported, mainly to the DRC, its requirement was only about 2.2 million t/a in 2024, which means that not all of the smelters can operate at capacity.

New copper mine capacity is planned in Zambia. Barrick’s $2 billion expansion at Lumwana will see production grow from 118,000 t/a to 240,000 t/a in 2028. In 2022, FQM also announced a $1.25 billion expansion at Kansanshi, which would expand the life of mine until 2040. The Canadian miner accounts for most of Zambia’s copper production – its Sentinel mine produces over 200,000 t/a and Kanshansi over 130,000 t/a. The Kansanshi expansion includes additional capacity at the smelter, which began operating in August 2025. Vedanta also wants to restart the Konkola underground mine, where operations had halted through a long legal battle with the previous government, and has announced a major refurbishment of its smelter.

Other consumers

Namibia is home to the region’s main uranium mining activities, at Roessing and Husab. Roessing takes sulphuric acid from the Tsumeb metal smelter to dissolve uranium ores, occasionally buying import tonnages via Walvis Bay. At peak production, consumption is up to 260,000 t/a of sulphuric acid, although it is typically lower. Huseb has its own dedicated 1,500 t/d sulphur burning acid plant.

Namibia’s other sulphuric acid plants are operated by Vedanta Zinc, which runs the Skorpion Zinc mine and NamZinc processing facility, and Dundee Precious Metals, which runs the Tsumeb copper smelter.

Infrastructure issues

One of the major issues that the region faces is a lack of transport infrastructure, which can lead to long lead times for sulphur or acid transport and high end-user prices. Sulphur has to be brought in from out of the region via ports at Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, Beira in Mozambique, Richard’s Bay near Durban in South Africa, Walvis Bay in Namibia, and Lobito in Angola. However, as Figure 1 shows, these are 1,600 – 3,000 km from the copper belt along poor roads and crossing several borders, often involving long queues and bureaucracy, tolls and bandits. Even so, taking sulphur on an outward trip and copper cathode or cobalt hydroxide on the return is proving to be a profitable operation for regional trucking companies. The DRC alone now imports over 500,000 t/a of sulphur. And with the world’s appetite for copper seemingly endless and copper demand projected to rise from 21 million t/a to 25.5 million t/a by 2030, leading to a potential shortfall of up to 6 million t/a from existing projects, it seems likely that Africa will be seeing more acid production and more sulphur demand over the coming years.