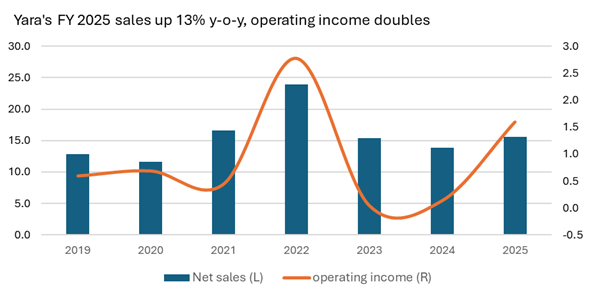

Fertilizer International 530 Jan-Feb 2026

23 January 2026

How to decarbonise coffee? Look at fertilizers!

AGRICULTURAL DECARBONISATION

How to decarbonise coffee? Look at fertilizers!

If decarbonising coffee starts with fertilizers, why don’t they feature more in conversations about sustainable coffee? In this article, Erna Maciulis of Proba outlines practical interventions that address fertilizer emissions from coffee growing. These can unlock significant progress towards Scope 3 emissions reductions – and be easily adopted without disrupting existing farm practices.

Better coffee from Brazil and Vietnam

If you drink coffee every morning, you’re taking part in one of the most global supply chains on earth. Also, did you know that 40% of your coffee’s carbon footprint is from fertilizers?

Most of coffee’s emissions happen long before the beans even reach a roaster. A large part of its carbon footprint can be traced back to the production and subsequent use of fertilizer on coffee plantations.

Regenerative agriculture dominates conversations about sustainable coffee. Shade-grown systems, agroforestry, and soil health practices are widely promoted. Those interventions matter. Yet fertilizer-related emissions are sometimes overlooked – even though they are measurable, cost-effective to reduce, and central to decarbonising coffee supply chains.

Downstream companies often assume these emissions are beyond their control. They’re not. Practical and accessible fertilizer-related interventions are, in fact, already available to reduce fertilizer emissions at scale. What’s more, they can fit naturally into existing farming systems.

Missing from the conversation

Fertilizers are an essential input for coffee production, but they’re also one of the largest sources of nitrous oxide (N2O), a greenhouse gas with a global warming potential 273 times higher than carbon dioxide.

So, why does fertilizer usage receive less attention than regenerative agriculture, deforestation, or social impact programmes?

1. Many downstream actors feel far removed from farm-level decisions. Coffee changes hands several times before reaching exporters and roasters. Buyers often work through traders or aggregators with limited visibility into their upstream partner practices. As a result, fertilizer strategies feel out of reach.

2. Interventions seem unfamiliar or complex to non-agronomists. Supply chain and sustainability teams may know how to support agroforestry or training programmes, but fertilizer optimisation sounds more technical. It isn’t, but the perception persists.

3. Cost concerns and uncertainty over who pays. Many farm-level interventions require upfront investment. Even when the cost is low, the responsibility for financing is often unclear, especially in fragmented markets dominated by smallholders. Proba believes that farmers should not bear the cost alone.

4. Traceability challenges that make impact hard to track. It’s difficult to connect fertilizer use to specific coffee volumes without systems to capture field-level data. This has made companies hesitant to rely on fertilizer interventions in their Scope 3 strategies, even when the impact is clear.

5. The narrative has long focused on land use and deforestation. Coffee companies have spent years addressing deforestation. This remains important, but the emphasis on land use has overshadowed fertilizer-related emissions, which are sometimes treated as secondary despite their scale.

All of this has resulted in fertilizer interventions being underrepresented in sustainability strategies. Yet addressing fertilizer emissions is one of the fastest, most measurable ways for coffee companies to make progress.

Brazil and Vietnam reveal the scale of the opportunity

Brazil and Vietnam produce nearly half of the world’s coffee. While having different farming systems, different regulatory environments, and different agronomic challenges, they share a reliance on fertilizers and a need for scalable climate solutions.

Looking at these two countries of origin should help downstream actors understand how fertilizer interventions can make an immediate difference and create a realistic picture of how these can be delivered.

Vietnam: high fertilizer intensity and water use pressures

Growing practices in Vietnam, the world’s largest producer of Robusta coffee, are highly fertilizer-dependent. Farmers often apply:

• Urea

• Phosphate fertilizers

• NPK blends.

Fertilizer rates per hectare tend to be high, sometimes higher than crop needs. Combined with over-irrigation, this puts pressure on groundwater in the country’s Central Highlands and increases nitrous oxide emissions from soils.

Vietnamese coffee growing is also highly fragmented. Millions of smallholder producers manage small plots, each with different fertilizer practices. While this makes coordination challenging, it also highlights the potential for intervention: even modest fertilizer efficiency gains across such a large number of farms can deliver substantial reductions.

Brazil: scale, intensification and climate stress

With plantations spanning roughly 1.9 million hectares, coffee growing in Brazil is vast in scale and notable for its large farm sizes and an increasing focus on irrigation. Fertilizer use is necessarily high – to supply adequate nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus to plants grown in nutrient poor soils – with many products imported.

Brazil has also faced historic deforestation linked to agricultural expansion, though producers today operate under the Forest Code and increasingly invest in soil health, agroforestry, and water conservation.

When it comes to coffee decarbonisation, what makes Brazil a standout for fertilizer solutions is the combination of:

• Strong focus on yield

• Increasing climate stress (especially droughts)

• Growing adoption of irrigation systems

• A willingness among many producers to innovate and adopt improved technologies.

Brazil shows how fertilizer efficiency can operate at scale – benefiting both farmers and downstream buyers that source large, consistent volumes.

“Fertilizer interventions are underrepresented in sustainability strategies. Yet addressing fertilizer emissions is one of the fastest, most measurable ways for coffee companies to make progress.

Which fertilizers are used most for coffee?

Across most coffee plantations, urea fertilizer is the primary nitrogen source. When urea is applied to soil, it can lead to:

• Direct emissions: N2O released during nitrification and denitrification.

• Indirect emissions: volatilised ammonia that later contributes to N2O formation.

Because urea breaks down quickly, much of its nitrogen can be lost rather than absorbed by plants.

Nitrogen stabilisers (inhibitors) as an intervention

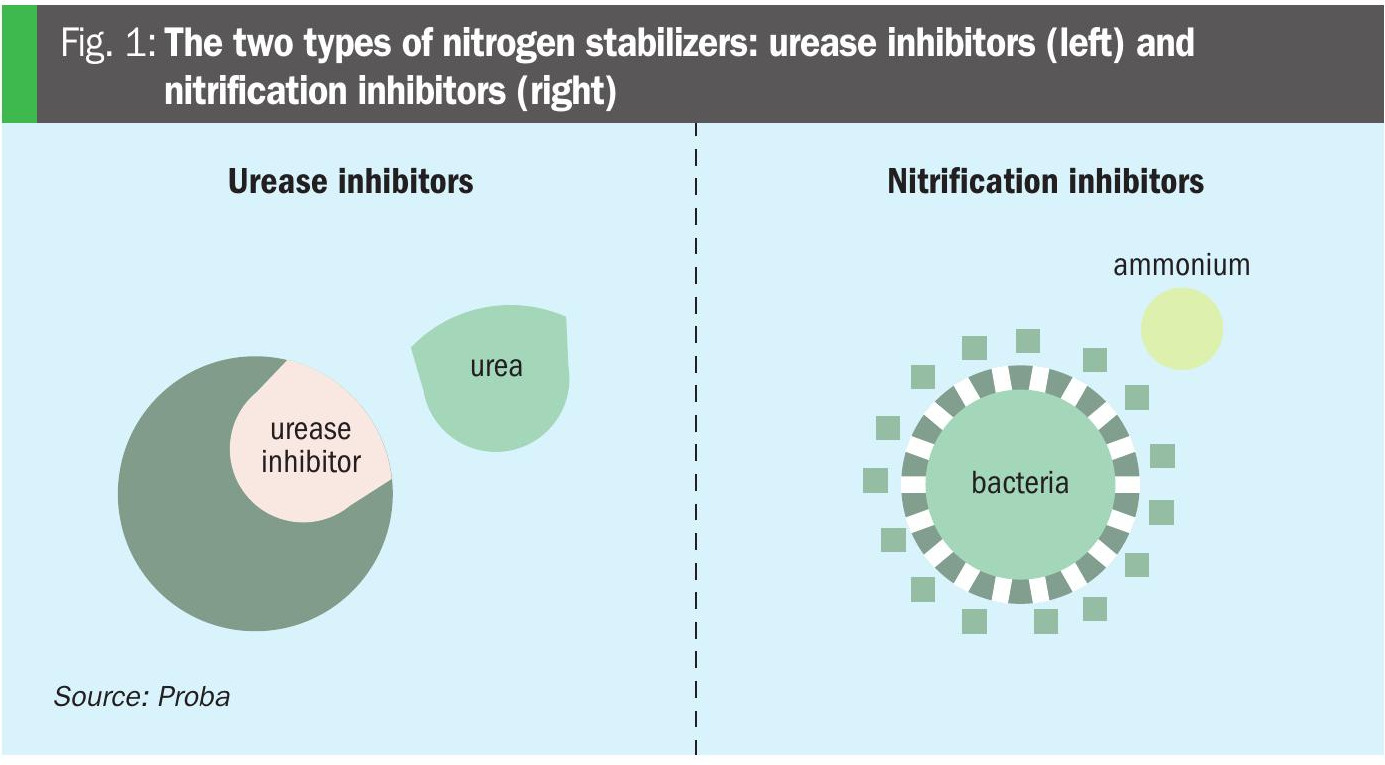

Nitrogen stabilisers are agricultural additives applied alongside fertilizers to reduce nitrogen losses and lower emissions. There are two types of nitrogen stabilizers: urease inhibitors and nitrification inhibitors (Figure 1).

Urease inhibitors slow the breakdown of urea, cutting ammonia loss, while nitrification inhibitors delay the conversion of ammonium to nitrate, reducing leaching and nitrous oxide emissions. By keeping more nitrogen in the soil for crops to use, stabilisers boost efficiency and help cut unnecessary greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

In coffee systems, nitrogen stabilisers can reduce N2O emissions by up to 50%, and even as high as 70% in some favourable cases.

Nitrogen stabilisers consistently demonstrate:

•Lower direct N2O emissions

• Lower indirect emissions from volatilisation

• Improved nitrogen-use efficiency (NUE)

• Stable or improved yields.

From a practical implementation standpoint, stabilisers:

• Fit easily into existing fertilizer practices

• Require no major equipment changes

• Are relatively low cost per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) avoided

• Can be adopted at both large and small scale.

For downstream companies, therefore, stabilisers represent an intervention that is accessible, affordable and measurable.

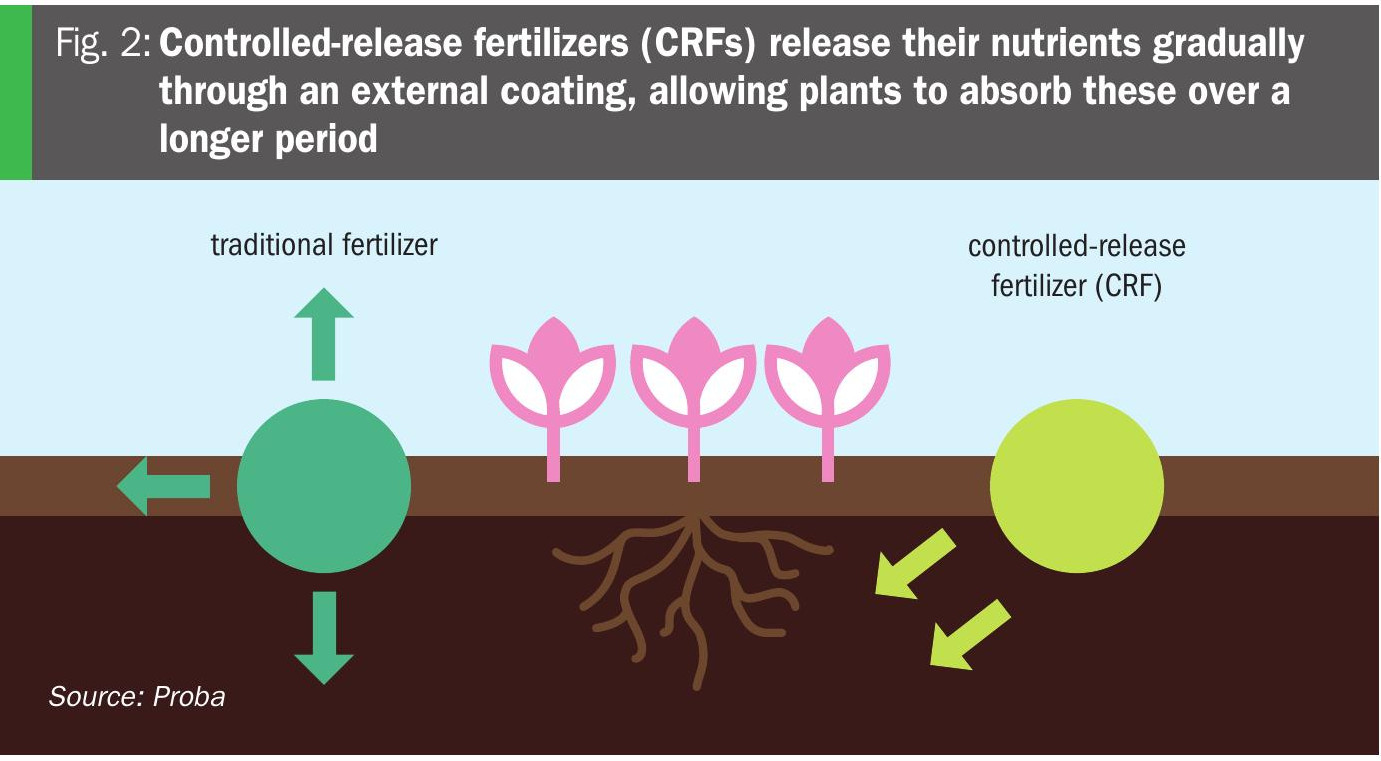

Controlled-release fertilizers as an intervention

Controlled-release fertilizers (CRFs) release nutrients gradually from granules through an external coating, allowing plants to absorb nitrogen over a longer period (Figure 2). This reduces losses through leaching or volatilisation and can reduce excess N2O emissions. The advantages of using CRFs include:

• More consistent nutrient availability

• Reduced labour (fewer applications)

• Improved NUE

• Potential for higher yields

• Lower environmental losses

• Measurable reductions across both direct and indirect emissions.

Like stabilisers, CRFs require minimal changes to farm operations. They are gaining traction in several high-input agricultural systems and are increasingly relevant for coffee production where irrigation and climate stress affect nutrient availability.

While CRFs can be more expensive per bag than conventional fertilizers, the overall cost as a decarbonisation option (per tonne of CO2e reduced) is competitive with other Scope 3 interventions, especially when combined with their crop yield benefits.

“Proba works with supply-chain partners to quantify and reduce fertilizer-related emissions across agricultural value chains. We help companies identify emission hotspots, choose effective interventions and support their implementation at farm level.

Reporting, traceability, and Scope 3 credibility

Fertilizer interventions are compelling for downstream actors because the results can be monitored and reported with confidence. When supported by verification frameworks, digital data collection, and clear quantification methodologies, companies can link reductions at farm level or sourcing region to their own Scope 3 claims.

Downstream companies can support fertilizer-efficiency interventions through:

• On-the-ground partnerships with cooperatives, agronomists, and local organisations.

• Carbon insetting models that link farm-level improvements directly to Scope 3 outcomes.

• Co-financed projects with traders or cooperatives to derisk adoption for farmers.

• Using recognised quantification and reporting frameworks to ensure reductions are credible and auditable.

These approaches help align incentives between buyers and producers, ensuring farmers are compensated for adopting interventions, while companies can report credible Scope 3 reductions.

Proba’s role in the sector

Proba works with supply-chain partners to quantify and reduce fertilizer-related emissions across agricultural value chains. We help companies identify emission hotspots, choose effective interventions, model the expected impacts, and support implementation at farm level.

Proba’s platform tracks adoption, quantifies results, and supports credible Scope 3 reporting. By focusing on proven technologies, like nitrogen stabilisers and controlled-release fertilizers, and tailoring deployment to local farming realities, Proba makes it possible for buyers to achieve measurable emissions reductions while supporting farmer productivity.

A practical path for coffee buyers

Coffee companies face lots of pressures: tighter regulations, expanding climate disclosures, and demand from customers and investors to provide sustainable coffee and meet climate targets. In our view, impactful solutions exist that are relatively easy to implement.

In particular, interventions that address fertilizer emissions:

• Can unlock significant progress towards measurable and verifiable Scope 3 reductions.

• Be easily adopted without disrupting existing farm practices.

• Complement regenerative agriculture rather than compete with it.

Encouragingly, coffee doesn’t need to wait for future technologies or complex overhauls. Practical tools are available today to reduce emissions, strengthen supply chains, and build long-term resilience.

Practical, confidence-building partnerships

Proven, farmer-ready solutions already exist, and companies that act now can secure measurable Scope 3 reductions while strengthening relationships with producers. Proba works with coffee buyers, traders, and cooperatives to design practical interventions, implement them with agronomists on the ground, and quantify the impact with clarity and credibility.

If you’re ready to explore what this could look like for your sourcing regions, Proba can help you identify the right interventions, model their impact, and build a practical plan with your local partners.

References