Nitrogen+Syngas 397 Sep-Oct 2025

16 September 2025

South America’s nitrogen industry

SOUTH AMERICA

South America’s nitrogen industry

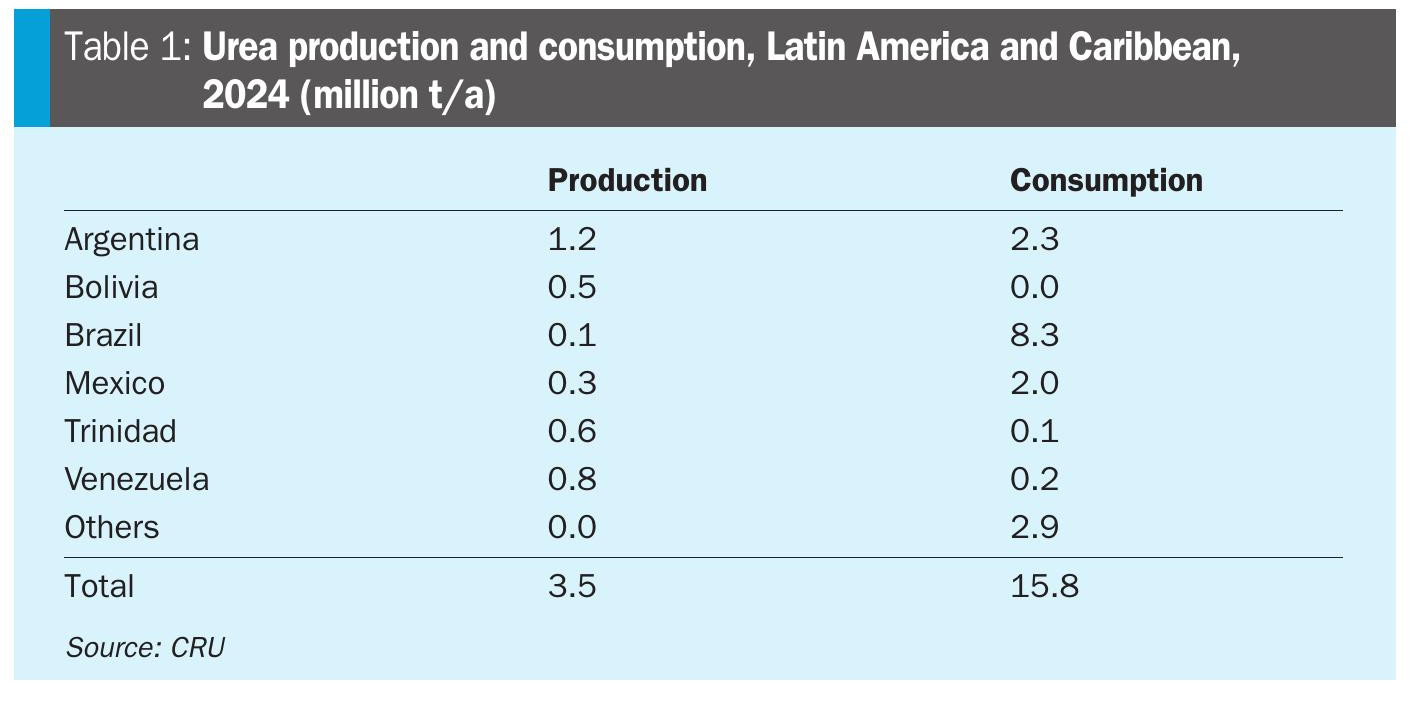

South America has become the largest importing region for nitrogen fertilizers, with Brazil overtaking India as the world’s largest urea importer. While there have been attempts to use local gas to develop a domestic nitrogen industry, these have faced challenges on a number of fronts.

The Latin America and Caribbean region has become the world’s largest net food-exporting region, according to the International Food Policy Research Institute. Its exports help to stabilise global food supplies and reduce food price volatility. Many countries of the region rely upon food exports, for up to 80% of their total export earnings in some cases, and agriculture is an important source of income and foreign exchange for many countries of the region. Fertilizer, particularly nitrogen fertilizer, plays a key part in sustaining this industry, and hence demand for fertilizer is strong across the region.

However, while there is plentiful oil and gas across the continent, attempts to develop this into a domestic nitrogen fertilizer industry have had mixed success at best. Brazil’s fossil fuels industry has been mired in corruption and several forced closures; Venezuela’s nitrogen industry – a flagship for the region in the 1990s – has contracted along with the rest of its economy under presidents Chavez and Maduro; Trinidad rapidly expanded ammonia production in the 1980s and 90s but more recently has faced gas shortages and production curtailments; and while Chile has a large domestic methanol industry at its southern tip, it has not managed similar for ammonia. One of the few success stories has been Argentina’s Profertil urea plant at Bahia Blanca.

Brazil

Brazil has the largest economy in Latin America and is 10th among the world’s top economies by nominal GDP, and 8th when measured by GDP purchasing power parity (PPP). It is a major global player in mining, agriculture, and manufacturing, with significant exports of iron ore, coffee, soybeans, and beef. The economy relies on both natural resources and a growing services sector. While recent growth has shown resilience, projections indicate a slowdown in 2025 due to higher interest rates and slowing household consumption.

In terms of fertilizer demand, Brazil’s fertilizer use has been rapidly growing over the past decade, as agricultural land is expanded. Cultivated area in Brazil has risen by 50% in the past 40 years, albeit often at the expense of clearing of rainforest areas. Coupled with increasing intensification of agriculture, this has meant that demand for urea – far and away the most popular nitrogen fertilizer in Brazil – has risen from 5.4 million t/a in 2014 to 8.3 million t/a in 2024. Overall, Brazilian nitrogen demand represents about 60% of that for the whole of Latin America, making it one of the most important consumers worldwide.

Brazil is all the more important in the urea market because it imports more than 90% of its requirement (see Table 1). There are three urea plants in Brazil. Camacari and Laranjeiras, with a combined capacity of 1.0 million t/a were originally owned by state oil and gas company Petrobras but both were closed down in 2018 due to poor production economics. After an abortive sale to Russia’s Acron fell through, in 2019 the plants were leased to chemical company Unigel for 10 years, but Unigel in turn was forced to close the plants down again in 2023, citing high gas feedstock prices making them uncompetitive compared to imported urea. In May this year Petrobras began court proceedings to take the two sites back under its control under a plan by president Lula de Silva to restart them.

The other urea plant, a 720,000 t/a unit at Araucaria, was originally owned by Petrobras but was privatised in 1993 as Ultrafertil. Under this guise it passed through the hands of first Bunge, then mining giant Vale, and then back to Petrobras in 2017, before being idled in 2020 due to economic difficulties at Petrobras. Petrobras approved a restart for the plant last year as part of its 2024-2028 strategic plan. The site’s automotive urea solutions plant began operations this August using imported urea from Yara, but the restart of the ammonia-urea plant is expected imminently, making it the only operational urea plant in Brazil. Aside from these, the only other nitrogen facility is an ammonia and industrial grade AN plant at Cubatao, with 600,000 t/a of capacity, operated by Yara.

In the 2010s, Petrobras tried to develop three new fertilizer complexes, at Linhares, Uberaba and Tres Lagoas, at a total cost of $6.5 billion, with the strategic goal of reducing or ending Brazil’s dependence on nitrogen fertilizer imports. However, a lack of natural gas availability and a recession in the Brazilian economy led to Linhares and Uberaba being cancelled, and work at Tres Lagoas, where a 720,000 t/a ammonia plant and 1.2 million t/a urea were reportedly 80% complete, being halted in 2014. Last year Petrobras approved the revival of the Tres Lagoas project, with work scheduled to recommence this year, and a targeted completion date of 2028.

The push to restart shuttered plants and revive stalled construction projects has come from the Brazilian government’s National Fertilizer Plan, which aims to reduce the country’s dependency on imported fertilizers. How successful this will be remains to be seen, but in theory it could result in 2.9 million t/a of operational urea capacity in Brazil by 2028. Even so, Brazil’s demand for urea is projected by CRU to increase to 9.8 million t/a by 2029, meaning that it will remain the world’s largest importer for the foreseeable future.

Another wrinkle for Brazil’s nitrogen industry has come from the direction of those imports. Prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Brazil imported much of its urea from Russia, but those volumes have fallen due to international sanctions on Russian banks, and more has been imported from the Middle East and Nigeria. A surprising increase has also come from imports of Chinese ammonium sulphate, which have risen rapidly from 2 million t/a in 2019 to 6.1 million t/a in 2024. Ammonium sulphate has increased its share of total Brazilian nitrogen demand from 14% in 2020 to 25% in 2024. Figures for 2025 show a continued increase, with May 2025 imports of AS from China up 47% year on year.

Argentina

Argentina is Latin America’s other major agricultural producer, and consumer of fertilizers. Argentina’s agriculture is a pillar of its economy, making it a global power in the export of commodities like soy derivatives, corn, beef, and wheat. The fertile Pampas region is particularly important for large-scale production. Argentina is the world’s third largest food exporter, with the agricultural sector accounting for 15.7% of gross domestic product (GDP), and around 25% of Argentina’s net exports.

Urea consumption was 2.3 million t/a in 2024, and though this figure rose during the 2010s, it has been relatively stable since 2020. It is expected to grow modestly to around 2.5 million t/a in 2029. Domestic nitrogen production comes from a single 1.3 million t/a urea plant, Profertil at Bahia Blanca, co-owned by Argentinian oil and gas firm YPF and North American fertilizer produce Nutrien, which almost exclusively produces for the domestic market. This leaves a shortfall of around 1.1 million t/a (see Table 1) which is made up with imports from North Africa (mostly Algeria and Egypt) and Nigeria. Various plans for a second urea plant have circulated over the past decade, but there is as yet no firm commitment.

Bolivia

Bolivia is not a major consumer of fertilizer but has large natural gas reserves, discovered in the late 20th century, which attracted numerous ammonia/urea project ideas. Bolivia supplies natural gas via pipeline to Brazil, and a site on the pipeline at Bulo Bulo, in the centre of the country, was chosen to build an ammonia/urea plant, under the auspices of state oil and gas company YPFB. After a long and difficult development process, the 726,000 t/a urea plant finally became operational in 2017, but was forced to close in 2019 due to high production costs. After maintenance was carried out to replace damaged equipment items it restarted in September 2021, and has operated successfully since then, though it has struggled to reach capacity. Production was 350,000 t/a in 2023, but rose to 545,000 t/a in 2024, with exports going to Brazil and Argentina.

Chile

Chile has no nitrogen fertilizer company, but explosives producer Enaex operates 850,000 t/a of ammonium nitrate production at Mejillones for explosives production. The site began operating in 1983, and has grown to four AN trains over the succeeding decades, the most recent capacity increase being in 2010. Aside from a small (15,000 t/a) electrolysis based plant using hydroelectricity, there is no domestic ammonia production, however – 350,000 t/a of ammonia is bought in from Nutrien to feed the site’s downstream nitric acid and ammonium nitrate production after the site’s ageing ammonia plant was sold, dismantled and transported to be rebuilt in China in 2013.

Enaex has become interested in the possibility of using renewable energy in Chile to generate ammonia. An 18,000 t/a ‘green’ ammonia demonstrator plant is under development, licensed by KBR, with completion expected in 2025.Spain’s Ignis Energy has also been developing a large-scale green hydrogen and ammonia project in Chile’s southern Magallanes region, with some of the strongest winds in the world. Ignis has been planning 2.25 GW of wind power network at Tierra del Fuego on Chile’s southern tip, with associated electrolysers to facilitate the production of green hydrogen and ammonia. In 2023, the company signed lease agreements for around 50,000 hectares of land for the project. However, the company recently signalled that it is slowing development until a market for green hydrogen and ammonia emerges, and has ended several agreements with local land owners in the face of an increasingly slow development process.

“Even though we firmly believe that this industry will develop and mature, the company is considering a longer time frame than initially planned and a reduction in the project to adapt it to this new reality,” Ignis said in a recent statement.

Mexico

Mexico is the third largest consumer of urea in Latin America, at 2.0 million t/a in 2024. As with many countries in the region, this runs far ahead of domestic production, which totalled 280,000 t/a in 2024. State-owned Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) operated several 1950s vintage ammonia and urea plants at Cosoleacaque, Chihuahua and Salamanca, and in 1996 Mexico produced 2.5 million t/a of ammonia and 1 million t/a of urea, but as with Brazil high gas prices led to the closure of much of the ammonia production by 2005. Attempts to refurbish plants and restart production at Cosoleacaque have been stymied by Mexico’s gas pipeline network, which does not connect the ammonia production sites in southeastern Mexico to the more extensive pipeline network in the north of the country, which is able to import cheaper natural gas from the United States.

The solution was to build a new urea plant at Topolobampo in Sinaloa state, on Mexico’s west coast, but the project, initiated back in 2014, has faced local environmental opposition and legal challenges, and was not given final approval until 2021. The site has been cleared and prepared and developer Proman achieved financial closure on the $1.5 billion project in 2023 and engaged thyssenkrupp Uhde to design and build the 2,200 t/d ammonia plant. However, the project remains controversial, and in June this year the Mexican government announced a review of the project’s permits.

In the meantime, another $1.3 billion project in Mexico’s northeastern Tamaulipas region appears to have begun construction earlier this year. The Oleum facility, situated close to the town of Reynosa near the Mexico-US border, will have the capacity to produce around 330,000 t/a of ammonia and 700,000 t/a of urea. Operations are expected to begin in late 2027, according to the company.

Casale has also been awarded a licensing and engineering services contract by Pemex for a new fertilizer complex at Escolin, Veracruz, including a 1,200 t/d ammonia plant and 2,125 t/d urea plant. Detailed engineering studies were conducted at the end of 2024, with production scheduled for 2028.

Mexico also has a number of green ammonia project proposals circulating, including CIP’s project Helax, Hy2gen, Asian Energy Capital and Tarafert. As yet there do not appear to be any final investment decisions, however.

Venezuela

Venezuela developed a gas-based urea industry at three complexes on its northern coast in the 1980s and 90s; Nitroven at El Tablazo in Zulia state in the west, Fertinitro at Jose in the east, and Pequiven’s Puerto Moron in between the two. The country’s total production capacity totalled 2 million t/a of urea in the early 2000s. Most of the plants were state-owned, but Fertinitro, completed in 2002, was a joint venture between state petrochemical major Pequiven (35%), Koch Nitrogen (35%), Snamprogetti (20%) and Empreseas Polar (10%). Koch became involved after PCS Nitrogen pulled out of the project in the late 1990s.

However, the advent of president Hugo Chavez in 1999 and his ‘Bolivarian revolution’ saw Venezuela’s economy slide. Much of the oil, gas and downstream industry was nationalised, including Fertinitro in 2010, and corruption and mismanagement left plants badly maintained. Pequiven did complete a replacement, 2,200 t/d ammonia-urea plant at Moron with financial support from China, which began production in 2014, but production at all of the sites continues to be dogged by interruptions in electricity and gas supplies. Venezuelan urea continues to be a valuable source of foreign earnings, but production was only around 800,000 t/a in 2024 out of a total capacity of 3.0 million t/a. President Maduro, successor to Chavez, announced a new 1.6 million t/a urea project last year, part funded with Turkish money, for the Fertinitro complex at Jose, but there is no sign of progress as yet.

Trinidad

Trinidad is an interesting adjunct to the Latin American nitrogen industry. Its boom years were in the 1980s and 1990s, when its relatively cheap natural gas prices made it attractive for suppliers to the United States, which was facing high gas prices. Ten ammonia plants with a combined capacity of 5.7 million t/a were developed on the island, as well as 1.3 million t/a of urea capacity and urea ammonium nitrate (UAN), most of these intended for export to the US.

However, Trinidad’s fortunes took a turn with the US shale gas boom, which led to the restart of idled capacity in North America and the construction of new plants, while Trinidad’s cheap gas prices had not been sufficient to develop new gas reserves at the pace that gas was being used for ammonia, methanol and LNG production, and consequently Trinidad’s ammonia plants have faced production curtailments due to gas supply shortages.

The shift in US trade flows also forced Trinidadian exporters to seek alternative buyers, including Europe, Morocco, and markets east of Suez. While these markets absorbed some volumes, they typically offered lower netbacks due to longer shipping distances. Moreover, Europe-bound ammonia will soon face additional costs under the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism from 2026.

These challenges are reflected in Trinidad’s declining exports. Between 2010 and 2024, ammonia exports fell from 5.2 million t/a to 3.2 million t/a, and its global exports share dropped from 27% to 19%. The forecast through 2029 points to stagnation, as growth in low-emissions capacity from the US and Middle East is expected to capture market share, particularly in Europe and Asia. Nonetheless, with Trinidad still supplying around one-fifth of the merchant market, its role remains significant.

Overall, Trinidad’s ammonia production has fallen from 5.4 million t/a in 2016 to 4.1 million t/a in 2024, and this latter level of production is expected to be maintained out to 2029.

A major importer

Overall, in spite of some returning and new capacity in Brazil and Mexico, and the possibility of some low carbon based capacity in Mexico and Chile, the Latin American region is expected to continue to be a major importer of nitrogen over the next few years, particularly Brazil, as well as Argentina to a lesser extent. Mexico may achieve some measure of self sufficiency using US imported gas, while Trinidad and Venezuela will continue to be net exporters, albeit at relatively lower levels compared to historical rates.