Fertilizer International 528 Sep-Oct 2025

13 September 2025

Pioneering CCm – patents, partnerships and production

FERTILIZER TECHNOLOGY SHOWCASE

Pioneering CCm – patents, partnerships and production

A strong driver behind the emergence of low-carbon fertilizers has been the close partnerships between start-ups and major companies looking to reduce Scope 3 emissions in their supply chains. CCm Technologies has been a particularly successful pioneer of this approach. Fertilizer International sat down with Pawel Kisielewski, the company’s CEO, to talk about its innovative fertilizer technology, achievements to date and UK production scale-up.

Introduction – from patents to production

CCm Technologies is a UK-based manufacturer of low-carbon fertilizers. The company was established in 2011 by four founding directors, Professor Peter Hammond, Pawel Kisielewski, Gordon Horsfield and Richard Morse. The company was granted its first patent in 2013 for a fertilizer production process based on carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS). This was followed by a series of other patents (on polymer technology, a heating unit and CO2 power generation, for example) over the next five years.

Innovation and intellectual property (IP) are at the heart of the company. CCm’s extensive library of global patents has grown to 44 granted in more than 50 jurisdictions worldwide. Of relevance to agriculture, its IP includes a technology that creates low-carbon fertilizers by capturing carbon dioxide from industrial power generation and then uses this to stabilise recovered nutrients, such as ammonia and phosphorus, from agricultural and industrial waste streams. Fibrous residues from food waste, sewage sludge and agriculture are also used as a substrate for these nutrients to improve nutrient delivery and enrich soils with added carbon.

Importantly, this fertilizer production process is ‘climate positive’ with an ability to capture and sequester carbon. This improves soil carbon and health – with every tonne of CCm fertilizer sequestering around 1 tonne of CO2 equivalent. Also, by recovering secondary nutrients, emissions from primary fertilizer production are avoided.

A successful Series A funding round led by Wittington Investments in 2019 was followed by a breakthrough year for CCm in 2020. This saw the launch of a project with PepsiCo/Walkers Crisps to cut carbon emissions from potato growing by 70%, and Yorkshire Water’s deployment of CCm’s recovery process to capture ammonia and phosphorus and convert these into fertilizers.

The company has also received a £1 million UK government grant to work with Severn Trent Water on developing commercial products from recycled wastewater and went on to secure £2 million of new funding from Innovate UK’s Sustainable Innovation Fund in 2021. It has also been collaborating closely with Tesco on low-carbon fertilizers since 2022.

CCm raised more equity in the third quarter of last year through a successful Series B funding round led by Frontier Agriculture. The company is currently building two low-carbon fertilizer plants in East Anglia and is continuing to partner with leading global food and drink manufacturers and leading retailers.

CCm has trialled inputs for its low-carbon fertilizer production from the following sites:

• The Nestle/Cargill cocoa shell pilot in York

• PepsiCo potato waste digestate plant (10,000 t/a of 12-4-4)

• Bagley Biogas farm-based digestate plant (2,000 t/a of 10-2-5 and 12-4-4)

• Water utility sewage sludge plant (10,000 t/a of various NPK formulations)

• Kew Technology digestate and biochar plant (1,000 t/a of 6-5-5).

A company powered by innovation

Could you tell our readers how CCm first came about – and how it’s able to transform low-value and variable waste streams into valuable crop nutrient products of consistent quality?

“The origins of CCm were at the school gate because Peter Hammond, our chief technology officer who’s also a visiting professor at Sheffield University, and I had children at the same school. Peter, who’s been working with CO2 for the best part of 30 years, had this eureka moment, turning a problem into the solution, realising that CO2 and ammonia were being attracted onto the surface of fibre.

“So, our primary piece of technology is the natural chemical reaction between CO2 and ammonia. Unlike many other technology solutions, you do not have to put it under pressure, heat to high temperature or add expensive enzymes or catalysts. It is just that ammonia and CO2 will react with fibre as the third input.

“The fibre is purely there as a substrate in the first instance. So, we can use grass, wood chip, straw, compost, any waste fibre, or even biochar. But primarily it is digestate from an anaerobic digester because the fibre lengths are small, which means we’ve got a large surface area to load with ammonia molecules.

“It’s a two-step process. So, in the first chemical reaction, you’ve got fibre with a large surface area, and you put a lot of ammonia molecules on it and then you pass through CO2 to form ammonium bicarbonate. In a perfect world, those ammonia molecules are waste sourced from somewhere within the waste hierarchy.

“There’s a plus and a minus to that. The plus is that it’s an exothermic reaction, so you get some heat energy from that. The downside is under relatively high temperature conditions that chemical reaction will reverse. So, we need to do a second chemical reaction, which is to add a calcium salt, to stabilise those nutrients.

“What you end up with is ammonium nitrate, the building block of fertilizer, and calcium carbonate, chalk essentially, all embedded and bound up in the organic matter. So, you can then create a fertilizer, it’s important to say a customised one, for the farmer.

“In our first year with PepsiCo, we did a 12-4-4 NPK, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium formulation. The following year, the farmers in PepsiCo’s supply chains said they wanted a bit more potassium, so we went to a 12-4-6. Then the following year, they wanted the potassium dialled back down. The message here is that it’s customisable.

“This technology is a cool process that uses CO2 as the binding agent for other waste streams and critically stabilises those nutrients. Because phosphates and nitrates in the wrong place – in a river in the West Country or Loch Neagh in Northern Ireland, or the Ganges or the Florida Keys – is not a good outcome. But, if you can stabilise using CO2, then waste nitrates and phosphate become valuable inputs at the front end of fertiliser production.

“For our patent portfolio, the top line number is 44 individual patents, as you rightly say. The actual numbers granted in 64 jurisdictions is 101 now, although there are obviously some repeats in there. Then there are another 29 pending applications.

“So, it’s a massive patent portfolio that costs us a huge amount. Not all of them relate to fertilizer, some of them are applications of the technology to power generation, heat storage and polymers.”

Partnering on decarbonisation

Agricultural decarbonisation and reductions in Scope 3 emissions require collaboration across the whole food system. CCm has exemplified this approach through its projects with PepsiCo, Nestle, Cargill, Tesco and others. How important are partnerships, in your view, for decarbonising agriculture and food products – and what can fertilizer input providers such as CCm offer the major supermarkets and fast-moving consumer goods companies?

“When we first set up the business, bringing a new product to market, we didn’t know who we needed to influence? Is it the consumer, as that’s quite tricky for a small company, or is it the government – and trying to convince them to give you subsidies?

“[Actually,] I think it’s a critical for low carbon fertilizer businesses not to seek government subsidies. It became clear [to us instead] that we were going to have to work [directly] with the regulators and the farmers. But the real drivers, the people leading this initiative, are the corporates.

“That’s because, on average, for global food manufacturers like PepsiCo or Nestle, Scope 3 [supply chain emissions] are about 80% of total emissions. So, as they seek to decarbonise, then Scope 3 is both their biggest and most difficult challenge.

“Then two summers ago, Nestle came out with a statement saying that as a company they would no longer offset – they wouldn’t, you know, be buying forests in the Amazon – and would only do insetting [in future].

“That’s actually made their lives more difficult, which is symptomatic of the leadership companies are prepared to show. I think Ramon Laguarta, the chairman and CEO of PepsiCo, has been the absolute standout leader [on sustainability]. But other people are doing it as well.

“It makes a huge amount of difference when the person committed [to low-carbon fertilizers] is running the show. PepsiCo’s chairman and CEO has absolutely been driving this, along with Jim Andrew, their chief sustainability officer. In the same way, Frontier’s new managing director Diana Overton is totally directing this too.

“We had the same [positive] conversation with Mark Schneider when he was Nestle’s CEO. If he says we’re going to do this, then everybody within the organisation realises they don’t have to use unnecessary political capital to try and force through new technology – because the person at the top has said ‘we want to see this happen’.

“We’re finding the same now at C-suite level with a European brewer. They bought in at the top table and that’s made life a lot easier.

“How does that then filter through [to us as a company]? Data is critical. If PepsiCo or Tesco are going to make a claim [on Scope 3 emissions] we need to be sure that the data we’re giving them is absolutely 100% bomb proof. That’s why we work with the Carbon Trust specifically, because they’re so reputable internationally.”

What is a ‘green’ fertilizer?

Defining what is a sustainable and/or lower-carbon fertilizer is not straightforward, given there’s no agreed standard definition of what a ‘green’ fertilizer actually is. How has CCm approached verification and certification of its processes and products by working with the Carbon Trust and others?

“You’re right, the whole of the climate space, not just within ag, is reliant on robust data which have a high level of integrity. So, data become key, which is the reason why we’re collaborating with Google Cloud who are helping us understand exactly how we can make data even more accessible to decision-makers.

“But if we go back to the fundamental challenge, fertilizer emissions divide between those that come from the manufacturing, the Haber Bosch process in the main, and those that happen in field. The Carbon Trust did an analysis in 2023 measuring the production emissions of our 12-4-4 NPK fertilizer. They said to us that a synthetic fertilizer with a comparable formulation had manufacturing emissions of about 1.2 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per tonne of product.

“[For our product] we were hoping to be, I don’t know, 70% better. The actual number they gave us for CCm fertilizer – which is verified and certified – is minus 0.9 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per tonne, mainly driven by the use of renewable energy and other embedded factors in our process. Critically, the ‘delta’ [numerical difference] between that CCm fertilizer formulation and the equivalent synthetic product was over two tonnes.

“The delta does change slightly for different NPK formulations. We think the latest NPK formula that we’ll be producing out of the two new [East Anglian] plants will have a delta closer to 1.5 tonnes.

“If you look at large food manufacturing companies, their supply chains are using well over half a million tonnes of fertilizer just in Europe [annually]. If you’re then multiplying that by a delta of 1.5 the difference [with synthetic fertilizers] is huge – and that’s just on the manufacturing emissions.

“The second piece of the equation is infield emissions, which are pretty difficult to scope properly because there are two elements. One is the nutrients lost to leaching and runoff into rivers and groundwater and the other one is NOx gases emitted to air. A two-year study of in-field emissions paid for by Nestle and Cargill found, in simple terms, [that CCm’s NPK fertilizer delivered] a reduction of about half in comparison with synthetic [fertilizers].

“Why is that the case? Well, first of all, you’ve got a lot more organic matter in a CCm pellet. That is organic matter being fed back into the soil and therefore reversing the decline in soil fertility from decades of industrial farming.

“What the CCm pellet also does, with calcium carbonate present, is act like a [fibrous] sponge that holds the nutrients. The lignin which is present in many of those fibrous materials, particularly straw-based materials, is really increasing nutrient [retention and] availability.

“One of the things that we’re working on is the ability to apply less CCm fertilizer but get the same yield outcomes – that came from a study five years ago. We’re in a position where not only are we starting to feed the soil and build up the soil organic matter but also finding – particularly around cereal crops – the ability for farmers to apply less nitrogen. Going forward, we want to apply less nitrogen to the ground if we possibly can, while maintaining yields.

“We also had a eureka moment talking to livestock producers who are huge buyers of animal feed. Now, if you use ultra low carbon fertilisers – it’s actually a negative number but it’s easier to say ultra low – to grow the corn, oats or barley to feed their animals, you’re decarbonising the front end. Then, if you can take animal waste to make the fertilizer, you’ll basically be decarbonising both the front end and the back end of livestock production.”

Scaling-up to meet demand

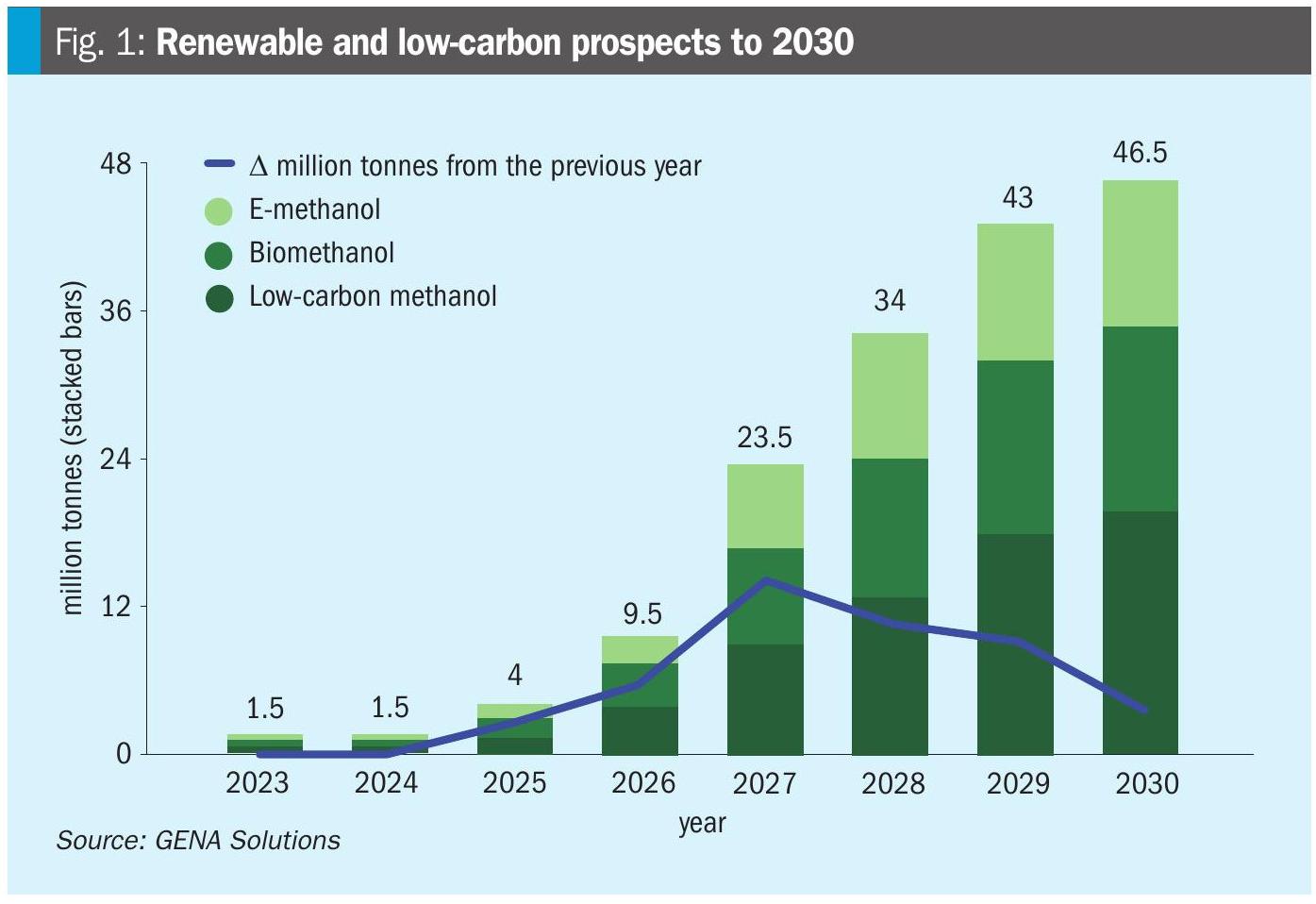

While largely viewed as a demonstration market currently, agricultural demand for ‘green’ fertilizer is scaling up as food manufacturers and retailers roll out regenerative farming and strive to meet their decarbonisation targets. How is CCm scaling up production and supply of fertilizers to meet current and future market demand?

“We have a distributed ‘hub and spoke’ business model. In East Anglia, we’ll have a couple of plants producing in the fourth quarter of 2025 within 30 miles of each other, drawing on waste resources that exist within the hub and spoke area. On their own, the [fertilizer production] capacity those two plants will provide will be about 53,000 tonnes by May 2027 – and upgrades mean that’ll be up to about 77,500 tonnes the following year.

“Then, in addition, we’ve got a Northern Ireland licensee with another 30,000 tonnes for May 2028 and we’ve also got a contract manufacturer that is likely to produce another 30,000 tonnes. So [CCm’s fertilizer production capacity] will be somewhere in the region of about 126,000-130,000 tonnes – through both our own facilities and from people who are licencing this technology.

“[Producing] about 126,000 tonnes [of fertilizer] by May 2028 is about five percent of UK current demand. That’s appreciable from a standing start. Those amounts I’m giving you are for the spring application season when fertilizers are most needed.

“In the main, we will be licencing the technology internationally. Firstly, because that’s the quickest way of doing it and, secondly, because customers like PepsiCo want us to do this to supply their overseas agricultural supply chain. We don’t want to be building a huge operation that will need managing beyond our own capability. So, licencing through partnerships is crucial.

“On funding, we did the Series B raise [last year] successfully led by Frontier Agriculture. Frontier have been around for about two decades, half owned by Cargill and half owned by AB Foods, which is ultimately owned by the Weston family. They’re basically the leading distributor of grain, seeds and fertilizers in the UK.

“That [Series B] round was really around the financing of the first production plant. Potentially, it’s possible we’ll do another equity round towards the end of this year, because the second plant emerged more quickly and is going to be bigger than we’d anticipated.

“But after that we then move into a position where we don’t necessarily have to use equity because the off takers – not just from people like PepsiCo who’ve been incredibly generous and supportive – but other customers who are either food manufacturers or retailers.

“[They’re] giving us long-term offtake over a 10-year time frame from which we can comfortably use debt funding. So, we’re looking at one of our last equity runs at the end of this year – and that’s probably us done!”