Sulphur 419 Jul-Aug 2025

16 July 2025

Australia’s acid conundrum

AUSTRALIA

Australia’s acid conundrum

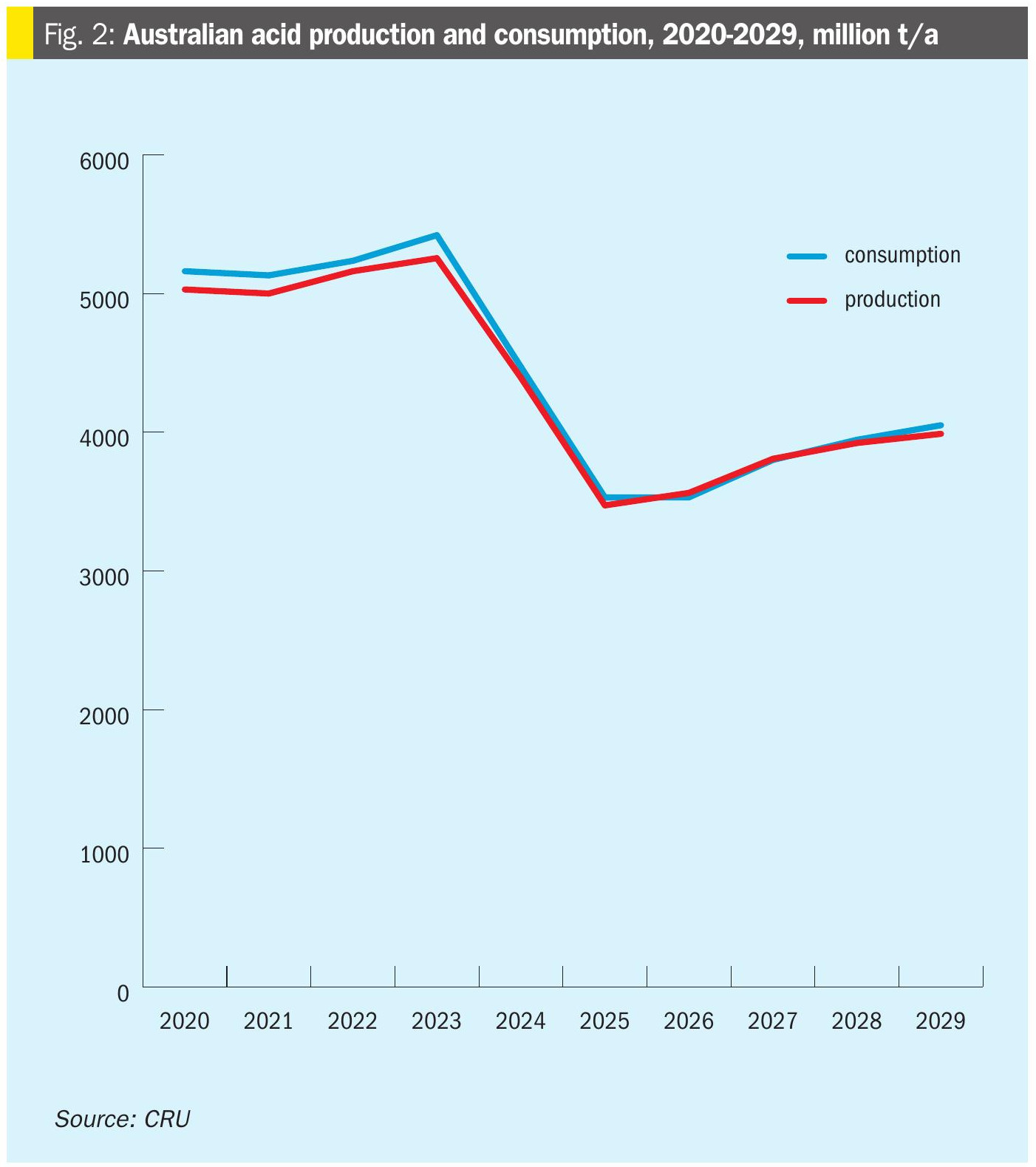

The progressive closure of smelter capacity in Australia poses potential problems for acid consumers across the country.

Last year CRU prepared a study on sulphuric acid supply for the Queensland government in the light of the closure of the Mount Isa copper smelter. At the same time, BHP announced the closure of its Nickel West smelter at Kalgoorlie in Western Australia for at least two and a half years. Other smelter closures or reductions in output are pending, all of which have the potential for major disruptions to flows of sulphuric acid across Australia.

Sulphur supply

Sulphur production in Australia is relatively limited, and comes from the country’s few remaining refineries. Australia’s oil production has been on a decline in recent years, down to 380,000 bbl/d at the end of 2024, from a peak of 550,000 bbl/d a decade earlier. Most of the oil comes from the North West Shelf off Western Australia, and is heavy but sweet. Heavy sweet crude is in considerable demand worldwide, and the oil producing region of Australia is on the opposite side of the country to most of its refining capacity, so Australia actually ends up exporting most of its oil production, and relying upon imported oil to feed its refining sector, coming from Malaysia, Indonesia and the Middle East.

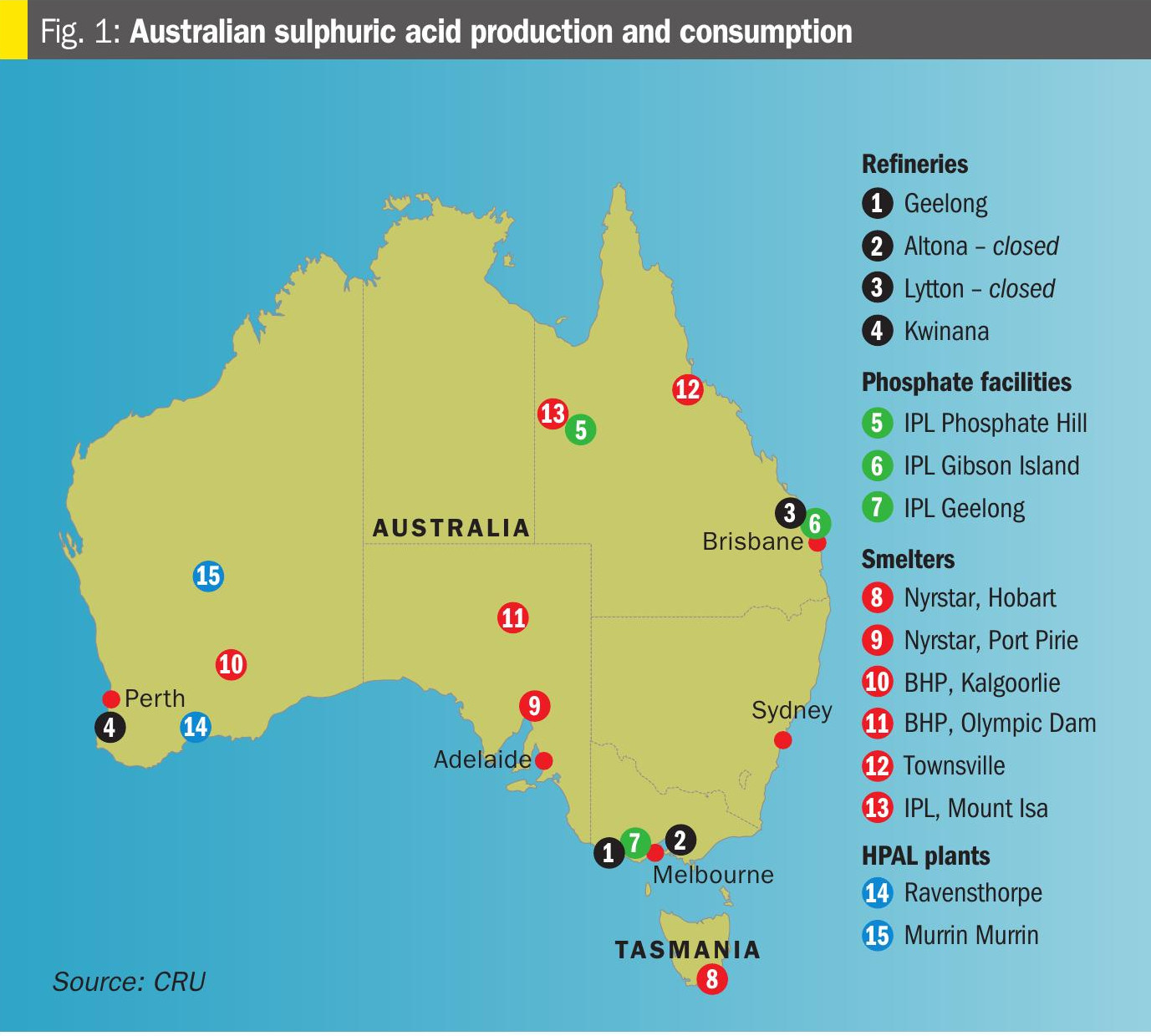

Australia’s refinery capacity has likewise fallen precipitately from around 750,000 bbl/d in 2011 to just 235,000 bbl/d last year due to refinery closures. Only two major refineries remain operational after the recent closures of Altona and Kwinana; Geelong, near Melbourne, and Lytton near Brisbane in Queensland. Others have been converted into oil import terminals, as it has been cheaper to import fuel from overseas than produce it domestically. Australian refineries have also not been set up to recover high volumes of sulphur. The result is that Australian domestic sulphur production is just 23,000 t/a.

Sulphuric acid

Until recently it had been a different story for sulphuric acid. Australia is a major minerals producer and had developed domestic smelting capacity to process some of these. A number of base metals smelters generated considerable volumes of sulphuric acid. Nyrstar operates two smelters in Australia; a zinc smelter at Hobart in Tasmania and a lead smelter at Port Pirie north of Adelaide with a total capacity of around 450,000 t/a of acid. BHP Billiton has a nickel smelter at Kalgoorlie in Western Australia with a capacity of 740,000 t/a of acid, and a copper smelter at Olympic Dam in South Australia with a capacity of 530,000 t/a of acid. Sun Metals, a subsidiary of Korea Zinc, operates a zinc smelter at Townsville in northern Queensland which produces 360,000 t/a of sulphuric acid. Finally, at Mount Isa in Queensland, Glencore operates a copper smelter which sends its off-gases to a sulphuric acid plant operated by Incitec Pivot Ltd with the capacity to produce 800,000 t/a of sulphuric acid. A further 400,000 t/a of acid can be generated additionally from a sulphur burning plant at the same site, usually when the smelter is not in operation. In total, there is around 3.5 million t/a of sulphuric acid capacity from smelting in Australia.

Closures

However, many of these smelters face economic and environmental challenges, and in recent years announcements and proposals for closures have been coming thick and fast. BHP suspended operations at Kalgoorlie in October last year due to low prices and overcapacity in the nickel market, with an announcement that the closure would last for at least two and a half years. Glencore announced last year that the Mount Isa copper smelter would be closing, with mining operations ceasing this year and the smelter running on imported concentrates until its closure in 2030. Nyrstar has also been facing economic difficulties and has reduced operating rates at the Hobart smelter by 25% and is looking to sell or close the Port Pirie smelter. All of these closures would remove nearly 2 million t/a of acid capacity from Australia.

Acid consumption – nickel

Australia has the largest reserves of nickel in the world, with estimated resources of 20 million tonnes, just under one quarter of the world’s total, most of it (>90%) in Western Australia. Australia was a pioneer of high pressure acid leach production in the 1990s via Anaconda Nickel at Murrin Murrin, Preston Resources at Bulong and Centaur Mining at Cawse. Bulong and Cawse were fed in large part by acid from the Kalgoorlie smelter, but a 1.45 million t/a sulphur burning acid plant was built to feed production at Murrin Murrin. However, all struggled with technical issues, and Bulong closed in 2002, Cawse in 2008 and Anaconda Nickel went through a financial restructuring, re-emerging as Minara Resources, which was eventually bought by Glencore. A new project also opened in 2008 at Ravensthorpe, run by BHP, which also included a 1.45 million t/a sulphur burning acid plant, but this was sold to First Quantum Minerals, who refurbished and reopened it in 2011, before it was idled again in 2017. The revitalisation of the nickel industry by the electric vehicle battery market did lead to a restart at Ravensthorpe in 2020, but the recent decline in nickel prices led to the plant being idled again in 2024. Glencore has continued to successfully operate Murrin Murrin during this time, however.

“While there have been a number of new phosphate projects in development, proceeding to production has so far proved an insurmountable barrier.

In the late 2010s and early 2020s there were a number of plans for new HPAL capacity in Australia, but some of the plans were predicated on acid output from smelter capacity which now looks doubtful, and the flood of Chinese investment into neighbouring Indonesia’s nickel HPAL industry looks to have brought prices even for Class 1 nickel to lows which do not currently justify investment in Australia. One possible exception is the Sconi Battery Minerals HPAL project at Greenvale, QLD, which has secured offtake agreements for 71,000 t/a of nickel production.

Acid consumption – uranium

Australia is also the world’s largest holder of uranium reserves. It is the world’s fourth largest producer, though output has fallen to 4,800 t/a of U3O8 in 2022 with the closure of the Ranger mine. Almost all production now comes from two mines; Olympic Dam and Four Mile. BHP uses an acid leach to recover the uranium from the ore at Olympic Dam; about 80% of the uranium is recovered in a conventional acid leach of the flotation tailings from copper recovery and most of the remaining 20% is from acid leach of the copper concentrate also produced at the site, with the acid coming from the nearby smelter.

Acid consumption – phosphates

Australia’s large acreages of farmland make the country a significant consumer of fertilizer. There is only one major phosphate producer, however; Incitec Pivot Ltd. The company’s largest site is at Phosphate Hill, Queensland, where it has the capacity to produce 950,000 t/a of finished phosphates. Phosphate rock comes from Australia’s only operating phosphate mine, the Duchess Mine 150km north of Phosphate Hill. Ammonia for MAP/DAP manufacture is produced on-site, and sulphuric acid is brought in from the smelter at Mount Isa, 160 km north.

IPL also operates a single superphosphate (SSP) plant at Geelong, Victoria, with a capacity of 350,000 t/a. Sulphuric acid to operate the SSP plant comes from Nyrstar’s zinc smelter at Hobart in Tasmania.

As with nickel, while there have been a number of new phosphate projects in development, proceeding to production has so far proved an insurmountable barrier. The Ardmore phosphate project in Queensland was to have produced 800,000 t/a of phosphate rock concentrate at capacity, but went into receivership in March this year. Verdant Minerals’ Ammaroo phosphate project, sited 300km north-east of Alice Springs, Northern Territory is also aimed at producing phosphate rock concentrate for export. Permits have been secured, but financing for the project remains an ongoing issue. Avenira’s Wonarah phosphate project in the Northern Territory, one of the largest known phosphate deposits in Australia, has also received mining permits, and Avenira says that it will begin mining operations in Q4 2025, with a final targeted capacity of 1.3 million t/a of phosphate rock, though this will all be for export with no processing in Australia.

Impact of smelter closures

The wind down of BHP’s Nickel West operations will remove acid supply from the company’s Kalgoorlie nickel smelter, representing around 550,000 t/a of acid. Given the remote location of the Western Australia acid market from alternative global supply, the question is whether it will be possible to replace the lost supply to allow demand to continue. BHP has internal acid consumption of around 250,000 t/a at the Kwinana refinery with by-product ammonium sulphate generated from the waste acid stream. BHP has also been directing acid to its nickel sulphate production line, although demand has only small as the operation has yet to reach full capacity. Third-party acid demand is split between lithium-based acid consumption around Kwinana, the Lynas rare earth operation at Kalgoorlie, and other industrial end uses, for a total of 170-200,000 t/a. This has left the operation exporting up to 100,000 t/a to the international market. It is assumed that the nickel sulphate production will end due to the loss of feedstock, reducing the net-supply impact to 300,000 t/a. Lynas is the only demand not located at the coast, and so has a greater logistical challenge to replace the lost supply. However, Lynas has announced that BHP will source acid to fulfil its supply arrangements to Lynas, with the initial term of the contract running until June 2027. This and other demand around Kwinana will require acid inflows from outside of the region, either sourcing acid from smelters in southeast Australia or via imports from the international seaborne market.

As far as Mount Isa goes, demand for sulphuric acid in the region has historically been dominated by phosphate fertiliser production at Incitec Pivot’s Phosphate Hill operation, with relatively minor demand coming from minerals processing (e.g., leaching of oxide copper ores) and industrial applications (e.g., water and wastewater treatment). Total demand for sulphuric acid in 2023 was approximately 1.23 million t/a, 95% of which was consumed by phosphate fertiliser production.

This demand has largely been met by Glencore’s Copper Smelter at Mount Isa and Sun Metals’ zinc smelter in Townsville. Some sulphur is also imported to feed sulphur burning acid capacity.

While the Mount Isa smelter is intended to continue operating beyond 2025, this is contingent on capital being available to maintain the asset, including the capital-intensive smelter re-brick every 4 years. It is unclear if the supply of economically viable third-party concentrates is sufficient for the smelter to operate at full capacity, and thereby supply sufficient acid feedstocks to meet current demand. In addition to potential supply chain disruptions, demand for sulphuric acid is expected to surge. A host of new critical minerals projects which fundamentally rely on sulphuric acid are in various stages of development across the State, including a suite of vanadium projects around Julia Creek, battery electrolyte manufacturing in Townsville, a large nickel-cobalt project near Greenvale and a host of copper oxide developments across the northwest. Total demand for sulphuric acid in 2035 could reach 2.86 million t/a from operating, committed and probable projects, and if all current speculative projects were to be developed, the total demand in 2035 could be as high as 5.23 million t/a. Options for additional supply of sulphuric acid include the importation of solid sulphur through the port of Townsville to feed additional sulphur burning acid capacity, and/or, potentially, the import of seaborne acid through the same route. The ability of Townsville to tranship sufficient volumes remains an open question, however. The CRU study did also examine the local production of sulphuric acid through the reprocessing of mine tailings to produce a pyrite concentrate that can feed either a pyrite roaster acid plant or a sulphur burner acid plant operation to produce sulphuric acid. A hybrid of this option produces sulphur prill directly from pyrite feedstocks. This technology is currently being developed by Cobalt Blue, who have demonstrated that it can recover valuable minerals, such as cobalt, from pyrite concentrate. The process produces elemental sulphur as a by-product, which can be granulated into sulphur prill and distributed to end users for sulphuric acid generation via a sulphur burner acid plant at the end user site.