Nitrogen+Syngas 395 May-Jun 2025

3 May 2025

Will energy uses drive future methanol demand?

METHANOL

Will energy uses drive future methanol demand?

Methanol demand is rising again after a few years of relative stagnation, but with the Chinese MTO boom largely over, it looks to be energy uses which will drive most future demand.

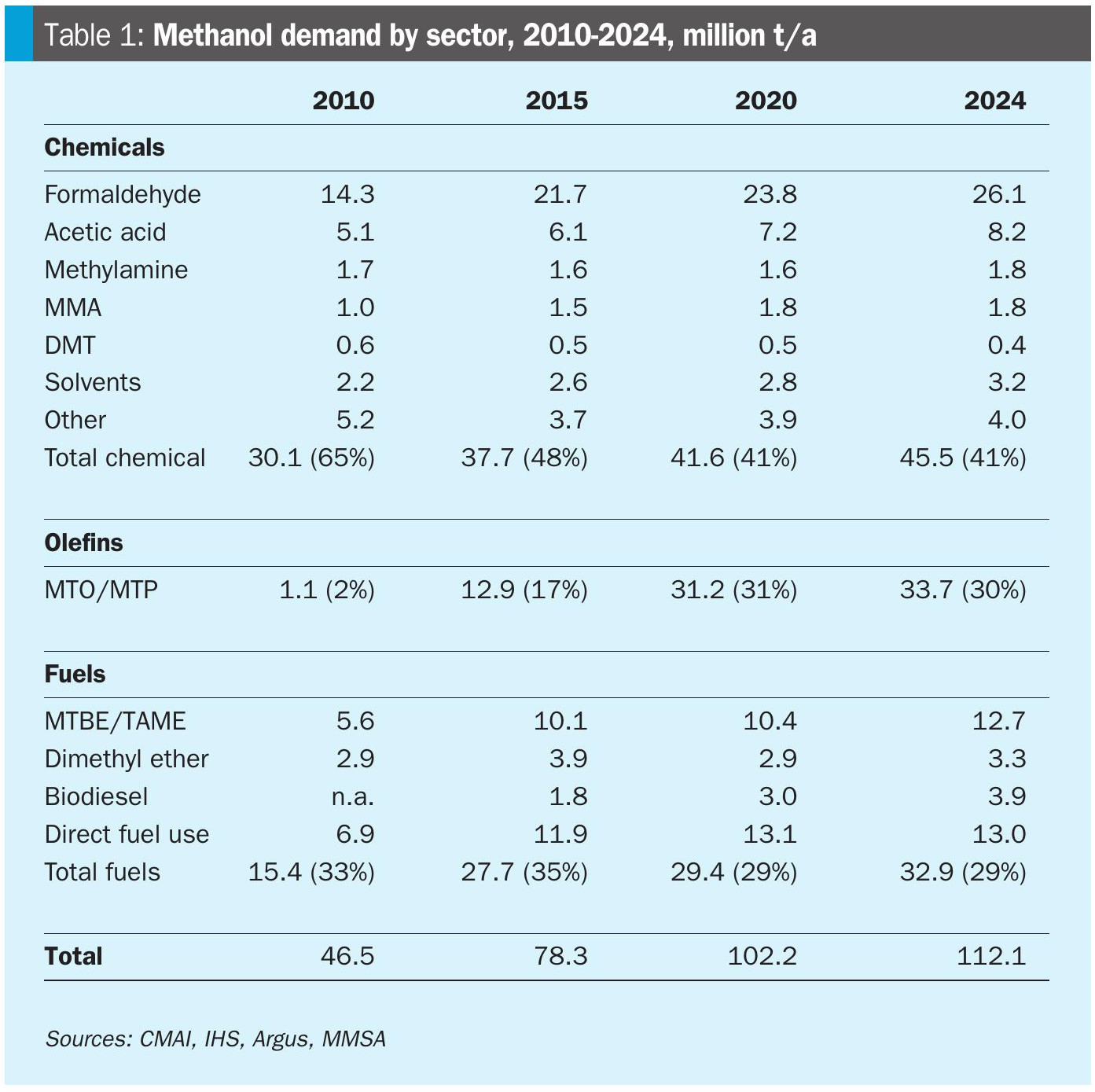

The world market for methanol is around 112 million t/a, about 55% of the size of the ammonia market. Around 40% of this is represented by traditional chemical uses such as formaldehyde and acetic acid, around 30% by olefins production, and around 30% by fuels uses (see Table 1).

Historically, methanol demand was almost exclusively used for downstream chemical production, mainly formaldehyde for resins, acetic acid, methyl methacrylate, methyl chlorides and other solvents. Because it was easily transported, as a bulk liquid at room temperature and pressure, production migrated to ‘stranded’ gas locations as a use for gas reserves that could not otherwise find a market, in places such as the Middle East, Trinidad, and at the tip of Chile.

The methanol market first began to shift away from this in the 1990s, mainly due to the development by Davy Process Technology (now part of Johnson Mat-they) and Lurgi (now owned by Air Liquide) of large scale methanol flowsheets. The move to 5,000 t/d and up plants allowed for economies of scale in methanol production which brought the cost down, and allowed it to compete with oil and gas derivatives both as a fuel and as a feedstock for olefins production. The methanol to olefins (MTO) process was developed by Union Carbide in the 1980s and commercialised by UOP in the 1990s, and Lurgi developed its own parallel methanol to propylene (MTP) process at the same time. This period also coincided with larger scale take up of methanol ether derivatives such as MTBE and TAME as clean burning gasoline additives, initially in the US, but increasingly spreading elsewhere.

But it was the large scale adoption of these technologies by a rapidly industrialising China in the 2000s that made the decisive shift in the methanol market. China sought to use methanol as a bridge from coal – of which it had an abundance – to fuels and olefins, which China otherwise had to import. Methanol derivative dimethyl ether (DME) became a widely used blendstock in liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), used for domestic heating and cooking in China, and methanol was also blended directly into gasoline at up to 10% to eke out gasoline supplies. In the 2000s, this was followed by methanol to olefins plants, either using domestic coal-based methanol, or even buying methanol on the open market.

As Table 1 shows, the impact of this on the methanol market was profound. Methanol use more than doubled in the decade 2010-2020, with more than half (ca 55%) of this increase coming from Chinese methanol to olefins plants. China also expanded both fuels and chemicals uses for methanol. However, as can also be seen in Table 1, the past few years have seen the rapid expansion of the methanol industry slow back to a more ‘normal’ level, with the covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine both disrupting markets. At the same time, Chinese coal prices have risen, and oil prices have fallen, making coal-based MTO plants less competitive. The Chinese methanol fuel and DME blending markets have reached saturation and China’s refiners have managed to slow the adoption of national fuel methanol standards, meaning only certain provinces permit it. There has been a large-scale build of domestic steam crackers to produce ethylene, in competition with olefins from MTO plants, and the slowdown in the Chinese economy has throttled back the need for ever-increasing volumes of plastics and other olefin derivatives, though demand from traditional chemical uses continues to rise.

US shale gas

Methanol production shifted decisively towards China during 2000-2020, mainly based on coal-based production. China now has 60% of all methanol capacity, though it operates at much lower rates than the rest of the world (around 58% compared to around 75% ex-China). But at the same time, the US methanol industry has had a remarkable turn of fortune, thanks to abundant and cheap shale gas. During the 1990s US capacity closed and production shifted to Trinidad and Venezuela where gas was cheap, the methanol being exported back into the US across the Caribbean. The availability of cheap natural gas has turned that around, and in 2024 the US produced 10.9 million t/a of methanol against domestic demand of around 7.5 million t/a. The country has returned to being a net exporter of methanol at the same time that Venezuela’s economic and political meltdown and Trinidad’s problems with gas supplies have reduced supply from those sources.

Europe and Ukraine

There has been a major impact upon methanol markets due to the war in Ukraine. Europe is a major consumer of methanol – the third highest region after Asia and North America, and also a large importer of methanol, while Russia has been a major exporter. In 2021, Russia exported 2 million t/a of methanol in 2021, and Europe imported most of that. High natural gas prices in Europe caused some shutdowns of European methanol capacity in 2021-22, with imports increasing particularly from the US. Russia had been gearing up for major increases in methanol production, but most of these projects have been put on hold due to the sanctions situation.

Elsewhere

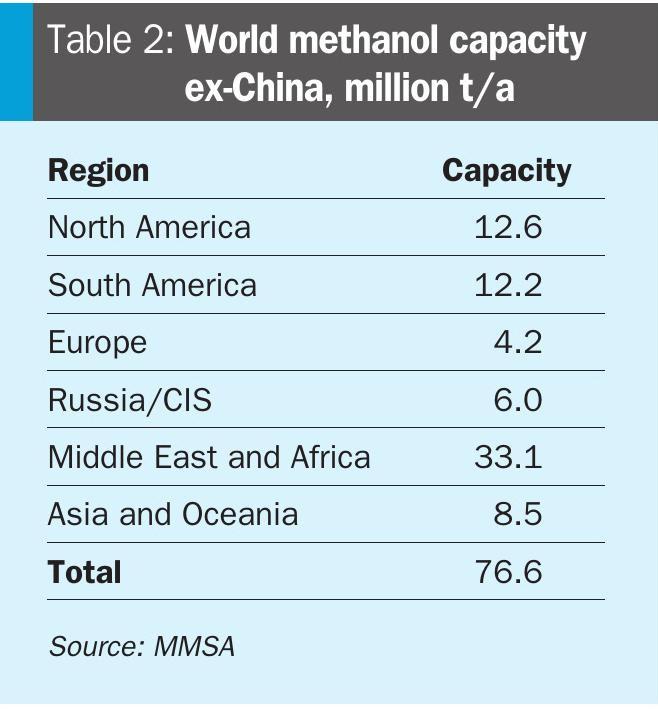

As Table 2 shows, the Middle East has the largest regional share of capacity outside China, and with only modest demand locally, it is by far the largest exporting region for methanol, with Saudi Arabia and Iran the largest producers. Outside of Iran, however, new plant building has slowed down as gas supplies become more constrained, while Iran has faced sanctions which have slowed its new capacity additions and ability to sell its product overseas.

India has talked about trying to emulate China’s move to domestic fuel and plastics production based on coal-derived methanol. In 2018, government think tank NITI Aayog launched its Methanol Economy initiative with the aim of increasing domestic consumption of methanol from its present 2 million t/a to 30 million t/a. However, in spite of some research and pilot programmes, so far nothing has progressed in terms of actual plant building.

Malaysia has become a methanol producing and exporting hub, with Petronas operating two plants at Labuan with a combined capacity of 2.4 million t/a and Sarawak Methanol another 1.8 million t/a plant which came onstream at Bintulu in December 2024.

Methanol as a bunker fuel

Methanol demand is now increasing at around 2-3% year on year, but there is scope for much larger increases in demand if it achieves widespread adoption as a shipping fuel. Methanex has used methanol as a fuel in its fleet of tankers, operated by subsidiary Waterfront Shipping, for some years, but interest in methanol has been galvanized by plans to decarbonise the maritime industry. The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) has set the target of cutting the sector’s carbon emissions by 50% in 2050 compared to 2008 levels. In Europe the change has been given extra impetus by the FuelEU maritime regulation, which came into force in January 2025. By levying heftier non-compliance costs on the use of fuels that emit higher levels of greenhouse gases, more vessel owners will likely be motivated to turn to alternative fuels to avoid higher costs.

Even greater impetus is likely to come from the IMO’s ‘green levy’, agreed in April 2025. The agreement mandates a $100 charge for every tonne of carbon dioxide emitted above an established decarbonisation threshold. Ships with a volume exceeding 5,000 tonnes must progressively reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions intensity by 30% by 2035 and 65% by 2040, compared to 2008 levels. Vessels that fail to meet the stricter benchmark will face a $100/tonne fee, while those that fall short of a less demanding target could be charged up to $380 per tonne. The new system also establishes a carbon credit market, allowing more efficient vessels to sell credits to those with higher emissions. The measures are set to take effect in 2028, though the US has expressed its displeasure with the decision.

There are a number of low carbon fuels under consideration by the shipping industry, including low carbon ammonia, low carbon methanol, hydrogen, biomethane, low carbon synthetic methane and other low carbon hydrocarbons, but there is as yet no firm consensus on which way the industry will go.

Methanol appeared to gain momentum after shipping giant Maersk began to focus upon it in 2022. A number of methanol fuelled vessels have been built or converted in recent years, including the Stena Germanica car ferry operating in the Baltic and several other Stena bulk carriers. Maersk is building 20 large dual fuel container ships that can operate on methanol, with eight delivered by December 2024. HD Hyundai says it has now received orders for 177 methanol-powered engine units for a total of 42 ships. By the end of 2023 138 methanol vessels were on order, putting methanol ahead of LNG as an alternative fuel for ships, and it is estimated that there could be 350 methanol fuelled vessels operational by 2030, requiring several million t/a of fuel.

Some of the shine came off methanol’s bunker fuel prospects in 2024 as Maersk appeared to have second thoughts, saying that it planned to order up to 60 vessels capable of running on biomethane. Since then Maersk has clarified that their owned share of the planned fleet renewal is 20 vessels registered as dual fuel methane propulsion systems from 9-17,000 TEU. However, they also confirmed that while technically being registered as dual-fuel liquified gas propulsion vessels, they would also include the option to convert the propulsion system to dual-fuel methanol. Maersk’s head of energy transition Morton Christiansen has said that biomethane “is much more available in Europe, where we have difficulty finding cost-competitive green methanol, which should still be the better scalable fuel option.”

Methanol bunkering options continue to increase. Singapore’s port authority is actively developing plans to incorporate methanol into its bunkering pool and is anchoring two of the largest green corridors globally, including the Rotterdam to Singapore Green Corridor and the Shanghai to Singapore Green Corridor. Maersk is working with the port of Yokohama in Japan to develop methanol bunkering there.

Blue and green methanol

Perhaps the biggest issue for methanol as a shipping fuel is now becoming supply. Much of the impetus behind the move by Stena, Maersk and others to methanol as a shipping fuel is predicated on using low carbon methanol, but the number of existing large scale low carbon methanol plants is relatively small. The methanol shipping tonnage above could require 7 million t/a of low carbon methanol by 2030, but it is far from clear if all of this could be available by then. Europe is on course to be producing 2.2 million t/a of low carbon methanol by then.

As with low carbon ammonia, the number of project announcements has dwarfed those that have made it to a final investment decision. In August 2024 Orsted scrapped development of its 50,000 t/a FlagshipONE green methanol project in Sweden citing slower than expected development of the market for low carbon methanol and lack of an offtake agreement. OCI sold its blue ammonia development to Woodside and its methanol business to Methanex last year, which includes two idled biomethanol plants and a blue methanol project under development. Lake Charles Blue Methanol was due to begin construction this year but is waiting on certainty on Inflation Reduction Act credits, which the Trump administration has tried to cut back on. Mexico’s Pacifico Mexinol is still on course to become the largest single ultra-low carbon chemicals facility in the world – producing approximately 350,000 t/a of green methanol and 1.8 million t/a of blue methanol from 2028, but again construction has yet to begin.

While low carbon methanol can be eked out by blending into conventional methanol to lower GHG emissions even if there is insufficient available to completely substitute low carbon methanol, something of a chicken and egg situation is developing where adoption as a maritime fuel waits upon production and vice versa. Global economic uncertainty and a slowdown in the petrochemical sector have not assisted with that process. Higher methanol prices over the past few months due to production outages in Malaysia and Equatorial Guinea, amongst other locations, may also be contributing to the general drift in low carbon methanol projects at present.

However, there are also signs that some companies may be attempting to square this circle. Maersk announced in April 2025 that they would be investing $100 million in C2X to advance the latter’s green methanol portfolio, with around 500,000 t/a of green methanol offtake up for grabs. Having put so much store on low carbon methanol as a future maritime fuel, Maersk appears to be prepared to invest to make sure that it happens, and if more shipbuilders and operators do likewise, then the present hurdle will be overcome. As with low carbon ammonia, guaranteed offtake agreements are generally the key to securing financing and final investment decisions.