Nitrogen+Syngas 395 May-Jun 2025

3 May 2025

The future of India’s fertilizer market

INDIA

The future of India’s fertilizer market

Dr M.P. Sukumaran Nair, Director of the Centre for Green Technology & Management, Cochin, India and former Secretary to the Chief Minister of Kerala discusses the challenges facing India’s agriculture and fertilizer industry.

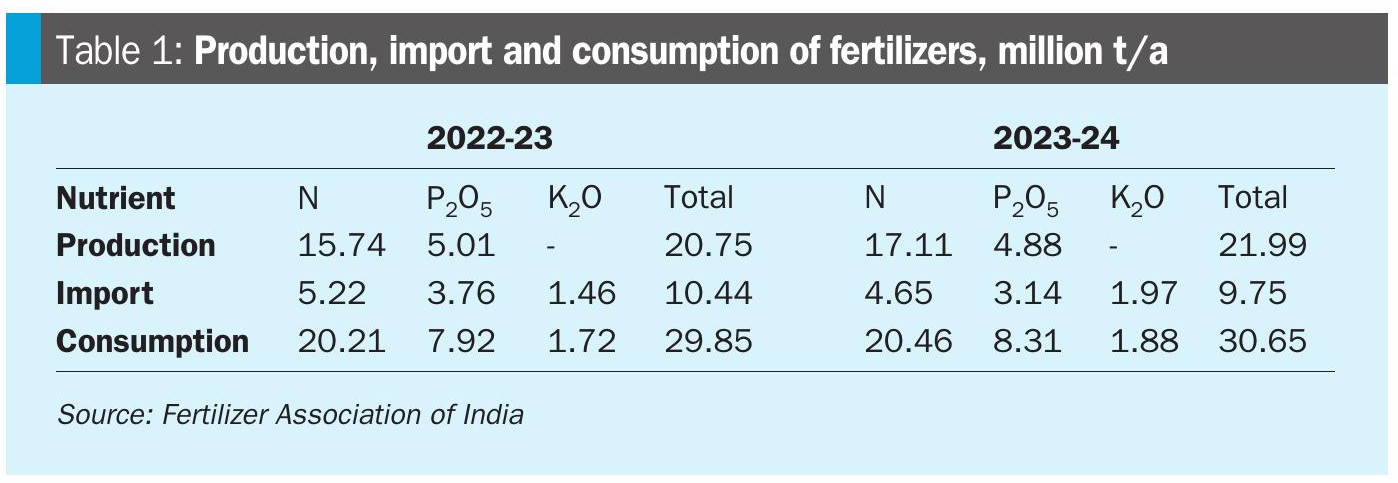

India, now the world’s most populous country, with a population of 1.45 billion people, depends heavily on mineral fertilizers to sustain its agricultural output and feed its people. Food grain production in 2024 was 332 million t/a, of which 55-60% can be attributed directly to chemical fertilizers. India is also the second largest producer of fertilizers globally and the market is primarily driven by government subsidies, increasing demand for agriculture, and the need for efficient farming practices.

Challenges

The major hurdles for Indian agriculture are declining crop response, imbalanced fertilizer usage, the subsidy burden to the exchequer to keep the price of fertilizers affordable for farmers, geopolitical uncertainties caused by wars and warlike situations in importing countries, and supply chain disruptions arising out of port and traffic restrictions.

Urea is the most consumed fertilizer in Indian farms. It is heavily subsidised to the level of one sixth of its current market price and is available cheaply across the country. Some of the Indian farm sectors have experienced declining crop response due to over-application of chemical fertilizers, especially urea, highlighting the need for balanced fertilizer use and an effective action plan to manage soil health. Excessive use of urea has led to upsets in the soil nutrient ratio, aggravated degradation and leaching which damage water bodies.

A major challenge before the government is the rising cost of fertilizers and occasional availability issues, particularly for subsistence farmers. Imports are often subjected to price rises and supply chain disruptions. Both of the above lead to increase in subsidies and cause a heavy burden on the state exchequer. Annual fertilizer subsidy expenditure has hovered around $15-20 billion for the past few years, and peaked to $29 billion in 202223. The union budget for 2025-26 carries a provision for $19.4 billion.

Geopolitical uncertainties including political events and geopolitical tensions are disrupting fertilizer trade and supply chains, affecting availability and prices, impacting farmers and agricultural production. This is exacerbated by transportation and logistical challenges caused by port closures and traffic disruptions.

Overcoming the challenges

Government initiatives include adequate provision for subsidies on fertilizers to make them affordable for farmers, efforts for promoting balanced fertilization and sustainable agricultural practices and launching several schemes to promote domestic fertilizer production and reduce dependency on imports.

Increasing domestic production

To counter supply chain disruption, the first step is to increase domestic production. Efforts towards rebuilding five brownfield urea plants – Ramagundam (in Andhra Pradesh state), Gorakhpur (Uttar Pradesh), Sindri and Barauni (Bihar) and Talcher (Odisha) – with a combined output of 6.35 million t/a of urea with natural gas as feedstock, have been a success story. Only FCI’s Talcher coal gasification-based ammonia-urea complex is yet to be commissioned. In addition, the government has also approved an 860,000 t/a urea plant for the public sector Brahmaputra Valley Fertilizer Corporation Ltd (BVFCL) as a replacement for two lower capacity old plants. The 2025 Union budget has proposed a new urea plant at the BVFCL site in Namrup (Assam) with a capacity of 1.27 million t/a.

Revamping existing plants

Most fertilizer manufacturers have already adopted and implemented projects and schemes intended for increasing of capacity utilisation, operational reliability, and energy efficiency so as to achieve the best onstream factor. Retrofit and revamp options, when available, are economically feasible, including improved equipment design, new materials of construction, and better performing catalysts, and can be easily incorporated into existing plants. Some have adopted advanced operational practices such as rigorous plant monitoring, digitised process control and online corrosion monitoring.

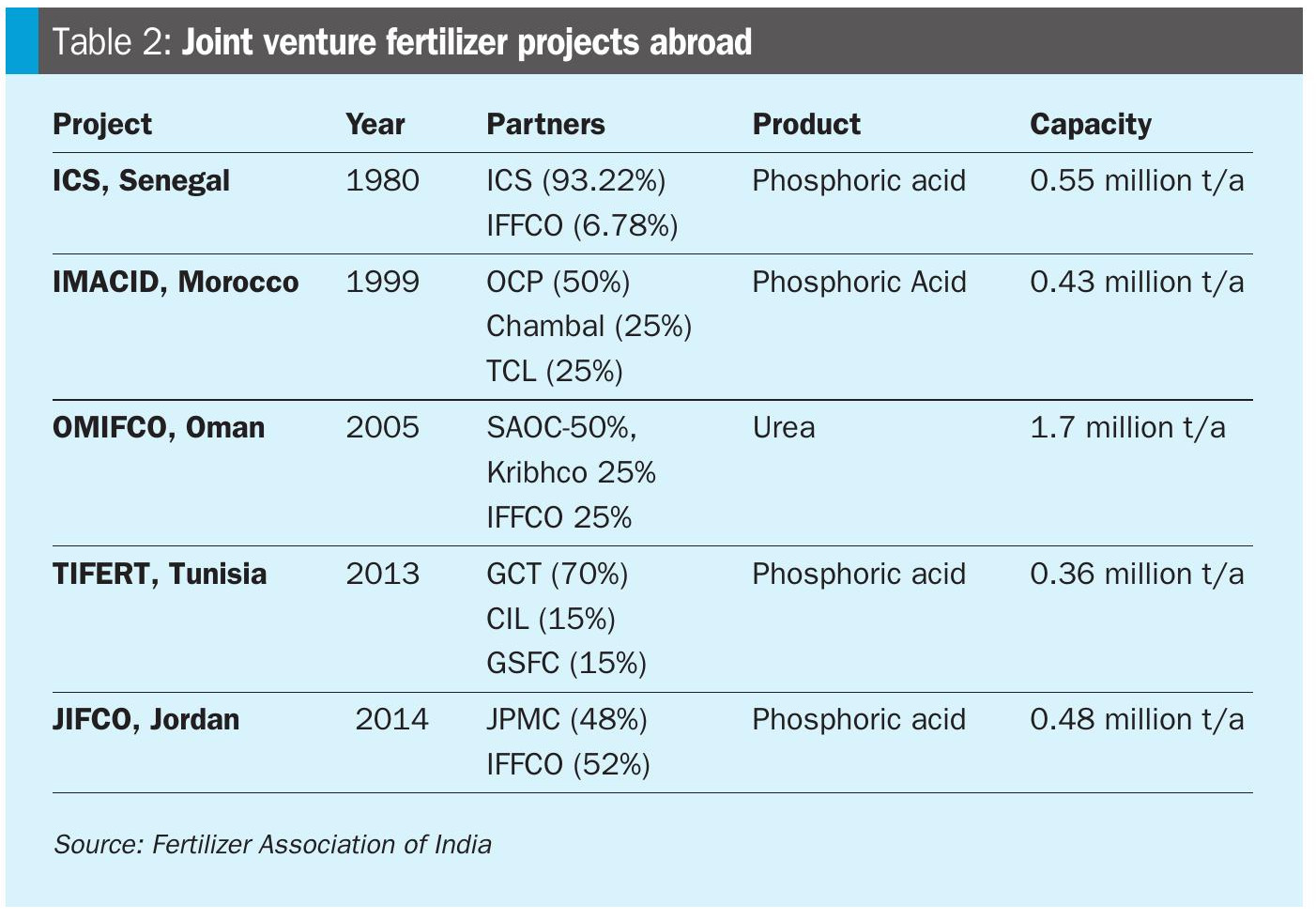

Joint ventures abroad

As mentioned earlier, India’s import dependency is around 25% of its urea requirement, rising to 90% in case of phosphates, either as raw material or finished fertilizers and 100% for potassium fertilizers. The government has been encouraging Indian producers to establish joint venture manufacturing facilities abroad in countries that are rich in fertilizer resources with buy back arrangements and to enter into long term agreements for the supply of fertilizer inputs or finished products to India. Producing urea and phosphoric acid in countries where natural gas is cheaply available was a successful option considered by the government to ensure the availability of urea (see Table 2).

There were also proposals for acquisition of fertilizer assets – production units, mines of raw materials etc – especially potash and phosphate mines in Russia, Canada, and Belarus. However, as the Department of Fertilizers could not formulate viable incentive schemes, such acquisition proposals have not yet taken off.

Import of fertilizers

India is heavily dependent on imports in the fertilizer sector and therefore maintaining a steady supply chain is important for the country’s agricultural productivity. The deficit in production – nearly 30% of consumption – is met by imports of raw materials, intermediates and finished products. During the 2023-24 fertilizer year, India imported 15.5 million t/a of fertilizer materials in addition to raw materials such as sulphur, phosphate rock and intermediates such as ammonia, phosphoric and sulphuric acid. The details are given in Table 3.

Better nutrient efficiency

Efficient use of fertilizers is important to optimal crop productivity, and economic gain to farmers and for avoiding pollution from leaching and farmland runoff due to excessive application. Serious efforts are required to achieve better nutrient use efficiency of applied fertilizers in the field based on nationwide soil testing and balanced administration of fertilizers. The government nowadays insists on a scientific administration of plant nutrients and promotes site and crop-specific nutrient management, the use of coated and delayed-release materials.

An optimal supply of soil nutrients over time and space to match the requirements of crops through the 4R principles can be achieved through crop and site-specific nutrient management (Right Product, Right Rate, Right Time, Right Place). These broad principles of such kind of a nutrient administration to the soil were developed by the International Plant Nutrition Institute in 1988.

Coating of urea with ingredients like sulphur, neem oil or polymers and the addition of micronutrients allow the controlled release of nutrients to the soil over an extended period. Nutrient release rate and duration are guided by coating thickness and soil temperature. Farmers are also being educated on the benefits of advanced techniques such as fertigation and integrated nutrient management.

Large-scale use of compost and farmland manure, biofertilizers, fortified fertilizers, and micronutrients must be promoted. The fertilizer sector, over the years, has undergone all the strains associated with the neo-liberal policies of the government. It needs to undergo a transformation by absorbing the new trends, scientific advancements and strategies that are associated with the production, crop nutrition and use of mineral fertilizers around the world.

Specialty fertilizers

Only a part of the nitrogen administered to the soil as fertilizers is absorbed by the plant and the rest leaches to the environment as nitrate or is lost to the atmosphere as ammonia or nitrous oxide, a potential climate distorting greenhouse gas. Various techniques are available to improve the nitrogen efficiency of applied fertilizers by product modifications. Controlling the release of nutrients to the soil by coating the product, stabilising the product with additives, delivery of product in a water soluble or in liquid form, and chelation with crop specific micro nutrients are all ways to add more value to common fertilizers to significantly improve nitrogen use efficiency. The International Fertilizer Association (IFA) lists controlled release fertilizers, slow-release fertilizers, sulphur coated urea, stabilised nitrogen fertilizers, water soluble fertilizers, liquid NPKs, and chelated micronutrients and boron as specialty fertilizers.

‘Nano-urea’

India’s fertilizer major IFFCO has developed ‘nano’ fertilizer grade urea and DAP which is expected to revolutionise the application of nitrogen fertilizers. Nano urea in liquid form has particles of 20-50 nm which, when sprayed on the plant leaf, are readily absorbed by the plant through the leaf stomata and releases nitrogen inside the plant. They also stimulate the enzymes involved in nitrogen metabolism inside the plant cells. They are also expected to minimise the environmental footprint by reducing the loss of nutrients from fields in the form of leaching and gaseous emissions which used to cause environmental pollution leading to climate change. They are available in liquid form as 500 ml bottles in India. The long-term crop response of nano fertilizers is awaited. If accepted widely, it will be a game changer to significantly reduce the necessity for massive future imports of granular urea.

Conclusion

Government efforts, though successful in transforming Indian agriculture, are yet to achieve its full scale intended objectives due to difficulties encountered in implementation. The following observations and suggestions are relevant as regards the future market for fertilizers in the country.

Consumption of plant nutrients per hectare of arable/agricultural land is still lower in India compared to major agricultural countries. Consumption of phosphate and complex fertilizers have registered an upward trend and this is projected to grow at approximately 6% through 2024-2029. An average 2-3% increase in overall consumption is expected in the near term, anticipating normal monsoon.

• Therefore, it will become necessary to increase the domestic production of fertilizers, particularly in the context of the ongoing energy transition as ammonia, the major fertilizer input material, is also slated to become a fuel of the future for long-distance hauling of ships etc. The government has announced a National Green Hydrogen Mission, which aims to make India a global hub for green hydrogen and ammonia production. The linkage with energy will invite more investment particularly from the private sector.

• In line with the country’s energy transition and proposed achievement of net zero emissions by 2070, a massive program to decarbonize the fertilizer sector, incorporating the carbon capture and storage (CCS) and electrolyser technologies will become necessary.

• Commissioning of plants under construction and debottlenecking of other operating plants with digital capabilities are to be expedited to increase production and improve efficiencies.

• Available low-grade rock phosphate deposits (Rajasthan etc.) may be effectively used through advanced beneficiation etc.

• More scientific application of fertilizers is needed. Promoting low nutrient content fertilizers such as ammonium sulphate and mono ammonium phosphate compared to high nutrient urea and DAP assumes paramount significance in the sense that such products supply only the required quantum of nutrients during the cropping season, the whole of which will be absorbed by the crops leaving little residue. Besides reducing wastage, it will also ward off soil degradation and environmental pollution.

• The Government should institute a countrywide program to promote the use of composts, agricultural wastes, green leaves, and farmland manure as readily available sources of manure for crops.

• For marketing and distribution of fertilizers, emerging technologies – e-commerce platforms, digital marketing, direct benefit transfers etc – must be made use of to improve efficiency and reduce losses and avoid delays.

Modern agriculture is often criticised for being energy and carbon intensive. A paradigm shift is needed to innovate current agricultural practices, with an emphasis on long-term sustainability. The government, together with the scientific community, needs to explore alternatives to traditional fertilizers, such as organic and bio- and nano-based options or precision agriculture techniques. It will also free up the disruption of traditional fertilizer products and raw materials supply chain arising every now and then on account of some reason or another.

The outlook for future market for fertilizers in India, thus, calls for more investment in production, technology access for digitisation and decarbonisation, retrofit and revamp of existing units and above all, farmer empowerment.